To my paid subscribers, thank you! You allow this space to remain free and provide me with funds to access additional research. This is invaluable. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you.

I understand the realities of capitalism as my family and I live paycheck-to-paycheck; if you are able to support this space with a paid subscription, I’d be incredibly grateful and promise to continue providing equitable access to women’s history. If a paid subscription is not possible, please know that your time is just as important and appreciated. Hitting the little heart button or sharing this newsletter goes a long way in regards to reach on this digital landscape and is just as appreciated.

An upgrade from follow to a free subscription also acts as a massive boost of support and promotes further engagement in the digital world, please do consider upgrading today.

If you’d like to financially support but are feeling uneasy about also supporting substack, you can tip here. Any bit helps, thank you! 💜

Thank you for your presence. Thank you for witnessing these women.

Medieval Women and Warfare

In 1141, Empress Matilda—the acknowledged rightful heir of the realm of England—and her supporters captured Stephen of Blois, the anointed king of England. You see, Stephen saw an opportunity to seize power and gave no pause at acting contrary to his sworn public words. Thus, he was king and Matilda, the daughter of conquest-kings and queens, was not. Matilda is often framed as an exceptional woman in history for her war mongering ways, but would it not also be true, secretary Hegseth, that anyone audacious enough to participate in pitched battle against an annotated king of England be considered exceptional? I mean, not many in history did just that—especially with a successful outcome—man or woman.1

In an interview with CNN, US Army veteran Elizabeth Beggs correctly noted, “lets not get it twisted. Women have been in combat since the beginning of history.” Adding an equalizing note, Beggs concedes “not all women are capable-just like not all men are capable.”2 Matilda’s ability to successfully impose her familial interests upon an anointed king when far more men in history attempted and failed the very same challenge, is just one medieval example to further Beggs’ initial point. Moreover, male recruitment numbers across all US military branches indicate men may no longer see themselves as capable of becoming sacrificial objects in the war games of others.3

But I digress, as that is not why we are here today.

In promotion for what I’m sure amounts to little more than a paperweight and waste of paper, you incorrectly stated, mister secretary, “traditionally—not traditionally, over human history—men in those positions are more capable.” If your logic, which then emboldens you to claim “we should not have women in combat roles,” weren’t so harmful, it would be comedic how boldly and incorrectly you reference history with a false sense of authority. Because so little space has been made (in the grand scheme of the study of written history) for women whose lived reality challenged patriarchy-propagated gender roles, and because men like you willingly try to minimize such contributions, too few know of the women who waged war. The women who conducted sorties, sieged towns, labored through birth pains only to emerge from childbed to have participated in the campaigning, and capturing of anointed kings. And you yourself, mister secretary, publicly claim camaraderie amongst these uninformed.

So, secretary Hegseth, grab yourself a pad and pencil because I’m taking you to school.

If we’re going to cast women such as Matilda as exceptional, uncommon—as your perception of history must—then the need arises to examine her contemporaries to investigate if she, in her warlike actions, was in fact an outlier amongst her peers—lending to your claims of women’s insufficient ability in combat-facing roles historically, ‘traditionally.’

Matilda lived and died in the 12th century. In fact, most of the women I mention below existed within a time of active crusading in the holy land—you know something of this, yes, mister secretary? Which meant that the men who have been credited with building and leading society, were instead off fighting xenophobic, religious wars. This absence, as is any absence of a cared-for loved one, was surely felt within their respective communities ‘back home.’ But this absence also left the women in charge to manage the day-to-day amongst the nobility. A power contemporary men of all classes would have recognized. In fact, due to men’s continued absence and early demise during crusade years, in prominent and influential counties such as Flanders, the lordship passed through the female line almost as often as it did the male one.4

In 1071, Richilde, countess of Mons and Hainut, led a pitched battle against her brother-by-law, for he was yet another man acting contrary to his publicly declared and sworn intentions. Though she would not be successful in this campaign overall, her ability to both lead armies and later engage with mercenaries to fight on her behalf highlights just how tapped-in women could be in terms of the established military economy of the time.5 As Amy Livingstone notes, “patriarchal abstractions did not compel male relatives or lords to try to prevent women from assuming such control or from shaping the future of the family and their children.”6 This view of women’s inferior access to yield successful authority—seemingly your view, mister secretary—is an anachronistic bias inherited from Victorian historians. It is also quite divorced from the lived reality of the past.

In 1147/8, Sybil of Anjou was enduring the late stages of pregnancy and childbirth; A personal battle which, speaking historically, cut the lives short of far too many women. While Sybil painstakingly pushed, the count of Hainut decided to attack Flanders, perceiving them vulnerable with a laboring wife and a crusading husband. Though a momentary win for the aggressive count, upon emergence from her childbed Sybil raised an army and employed a long practiced military tactic in retaliation: A campaign of scorched earth. So impactful was this campaign that the count quickly submitted to Sybil’s will.7

Your expressed paradigms, mister secretary, imply that Thierry, count of Flanders—a man with a commitment to the crusades and a distinguished military record to accompany it—“lowered (his) standards” by allowing his wife to lead in a combat-facing role. The men of the 12th century that devotedly followed her into battle likely did not perceive her as less capable and I’m left to wonder why you might. Georges Duby, often hailed as one of the most influential medievalists of the 20th century, defined the entirety of the Middle Ages as “resolutely male,” without ever acknowledging the inherent bias such an argument both projects and upholds.8 Do you mean to imply the same, mister secretary, in regards to military effectiveness throughout human history when you stated “men in these positions are more capable”?

During those ‘masculine’ Middle Ages, Blanche of Navarre (12/13C) exquisitely exemplified why noblewomen required a complete understanding of all aspects of lordship, including the administration of warfare.9 Financial records indicate Blanche’s lordship demanded of her the planning of campaigns, fulfillment of fortifications, the hiring of mercenaries, and leading of forces into both ancillary and principal battles. Blanche—in the context of the same human history you reference, mister secretary—subdued a rebellion, employed an array of military tactics to achieve her goal and ensured her son inherited both his father’s and her own lordships in entirety. Even amidst the challenges of civil war, Blanche expanded the borders of her domain and amassed more personal authority in a time thought void of such. As Katrin E. Sjursen rightly identifies, “noblewomen performed these duties on a daily basis, indicating military concerns occupied them constantly and their participation in warfare was anything but temporary.”10

To think of a history of warfare—which the Middle Ages occupies much of—as inherently male, and furthermore as a strictly masculine capability, serves only to advertise a personal bias in historical consumption, nothing more. The very same lands that contributed a substantial presence among the Knights Templar boasts centuries worth of warfare-rich contemporary evidence of women’s capabilities in the theater of war. To imply otherwise is repressive revisionism at best…

As Eileen Power identified over 80 years ago, a “rough and ready equality” existed between spouses, regardless of imposed church views upon an institution that straddled the religious and secular worlds.11 This lived reality of partnership in lordship is evident even amongst the most highly praised patriarchs, even amidst the reality of hierarchical patriarchy and accepted misogyny.

Eleanor of Aquitaine, queen to famed patriarch Henry II of England, is infamous for her participation within the crusades. Prior to her marriage with Henry, Eleanor was married to Louis VII of France, and had it not been for Eleanor’s fervor and deep resources both financial and militant, Louis likely would not of heeded the call of crusade:

“For she could muster more soldiers…and the revenues of her duchy were indispensable.”12

Aside from being an active participant in the courts and greater politics of both realms during her respective tenure of each, Eleanor’s ability to step into the intercessory role required of women in lordship is more than just evidence of performative femininity. It speaks too towards partnership under imposed performative gender rules.13 This role of intercession is often framed within historical accounts as one of the few accepted forms of feminine power, as it highlighted both prescribed meekness and implied subordination in one fell swoop. But in terms of power and who possessed it, there are many documented cases in which a queen performed this function of partnership and was able to influence a king where countless Lords could not.14

Though this form of power was indeed submissive in nature, more overt forms of feminine authority were clearly recognized in every crevice of society.15 At the beginning of the 12th century, Hersende of Champagne and Eleanor of Aquitaine “founded or supported female (religious) houses with male members obedient to an abbess.”16 Nor should we think of this power as limited to those performing church duties or imperialist patriarchy:

“Post-Conquest elite laywomen could and did exercise power and agency as a consequence of their social status and claims to property, wealth, and lordship. Their opportunities to wield power shifted due to a number of factors over the course of the twelfth century, but they were rendered neither powerless nor inconsequential.”17

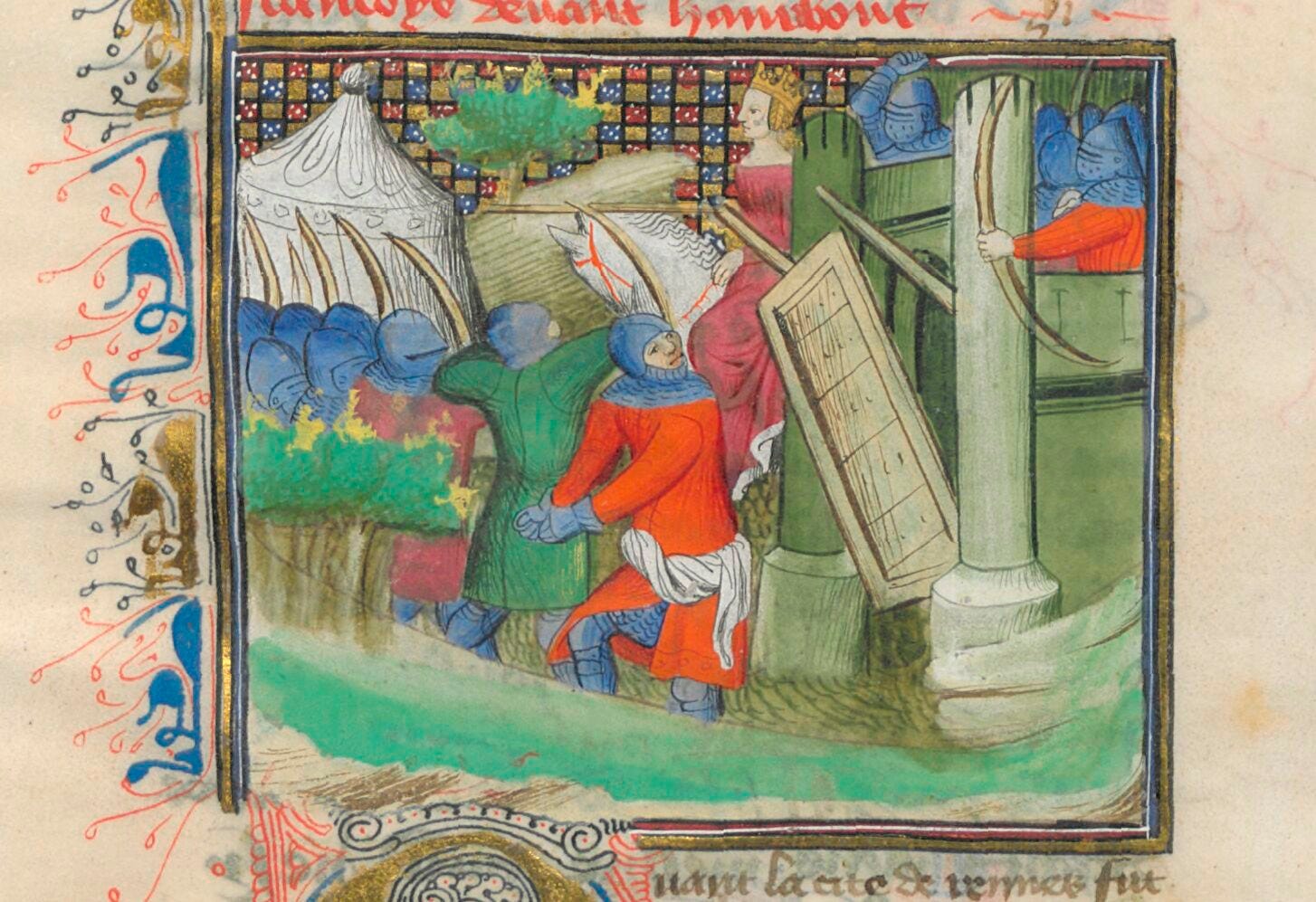

Queen of top patriarch Edward III of England in the 14th century, Philippa of Hainault is often cited as the quintessential intercessor. In some renditions of the following events she is swollen with pregnancy, crawling and pleading to her husband’s gentler side, in others she is not with child but nonetheless pleading and crawling.

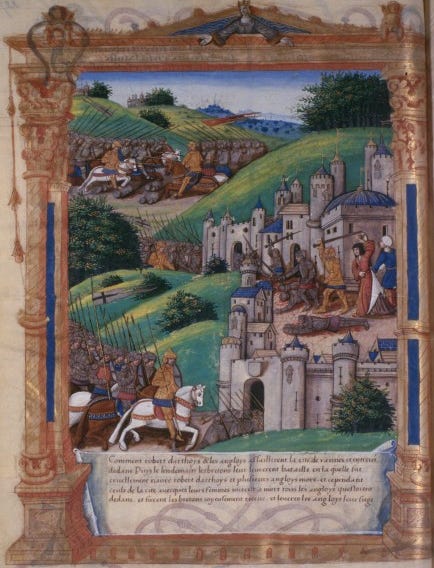

In 1347 after an excruciating eleven month siege of Calais, the city fell to the English. The six ‘Burghers of Calais’ presented themselves exactly as Edward demanded and threw themselves and the keys to the city on the floor before him and his queen. With the whole of the English army looking on, Edward demanded their immediate beheading—a sentence which equally startled the king’s top advisers and Frenchmen alike, drawing loud condemnation from all. It wasn’t until Philippa pleaded with her husband, employing her side of partnership in lordship and a very public act of influence, that Edward decided to instead eject all French citizens from Calais with their heads still naturally perched atop their bodies.18

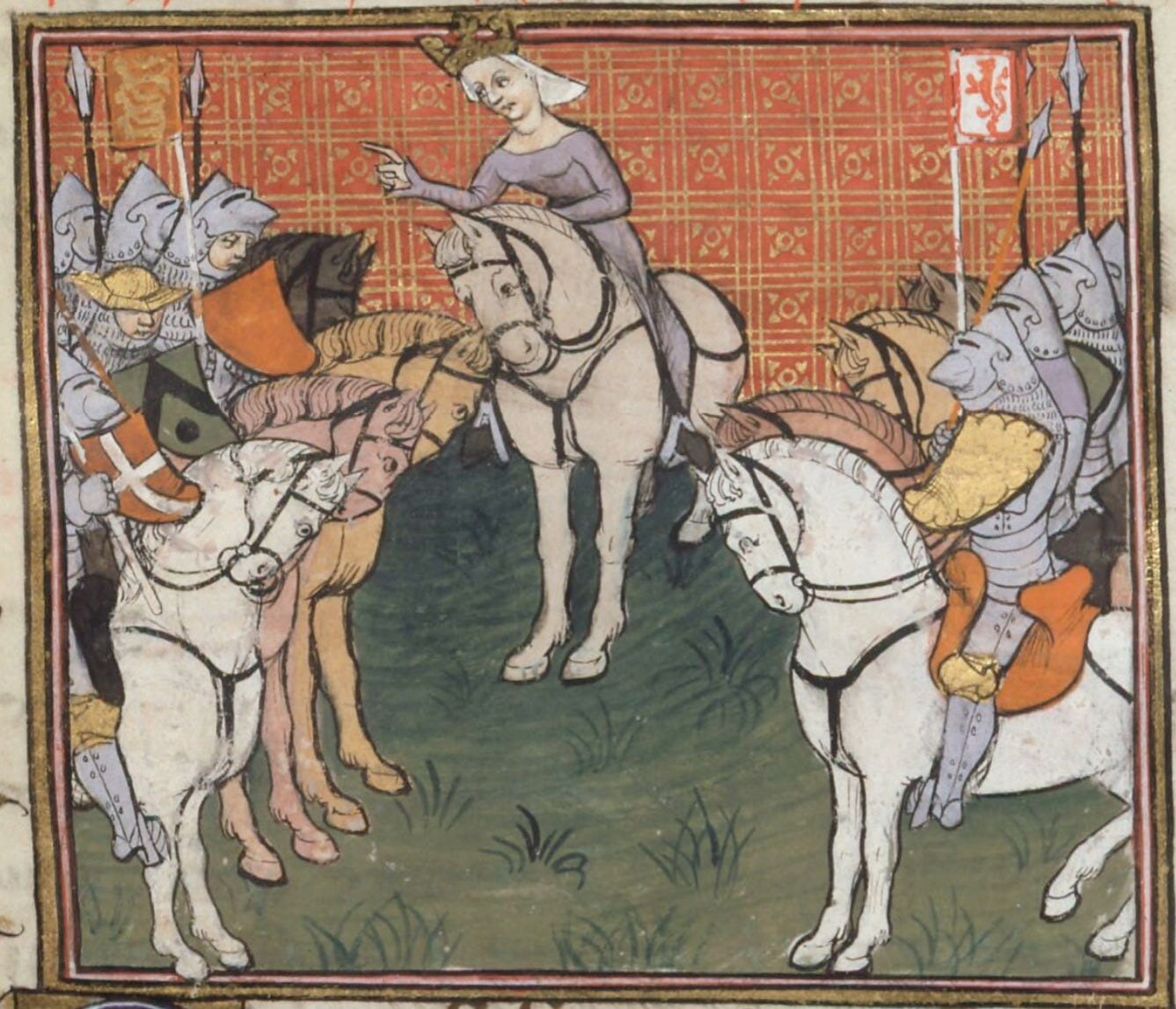

This intercession, Philippa’s purported submission to her Lord, has long been considered one of the few allowable showings of feminine influence upon the public domain in the Middle Ages.19 But the very same year that the siege of Calais began (1346), Philippa was siting astride a white charger, rallying English troops to protect king (absent in France) and country against the invading Scottish.

“It was now Philippa’s turn to do battle-royal with a king. As a diversion in favor of France, David of Scotland advanced into England a fortnight after the battle of Cressy and burned the suburbs of York. At this juncture Philippa herself hastened to the relief of her northern subjects.”20

The English, so stirred by Philippa’s influence, went on to defeat the Scottish at the Battle of Neville’s Cross where king David was captured and held as a prisoner of England for 11 years. Often within the confines of the queen’s various landed estates.21

Alongside rallying contingents of armed men to victory in pitched battles and retaliatory sorties alike, these instances require us to look beyond the traditionally accepted patriarchy propagated position of men-at-arms possessing the “true basis of power behind a female figurehead” and reckon with the reality of not only recognizable female authority, but expected female authority in combat roles and military leadership that has been voided—almost in it’s entirety—from human history.22

Eleanor of Aquitaine was not unique in context of women possessing power during the Crusades nor was feminine power unique within the crusader states themselves.23 If we look beyond the Eurocentric canon we see women throughout the world assuming practical authority through the very patriarchal domination techniques (i.e. war) you claim belong to the men of history, mister secretary.

During the third crusade, Shajar al-Durr, an Egyptian sultana, organized the defense of her kingdom from the Western barbarians—the French led by king Louis IX—ultimately defeating him at Damietta.24 Though historically we refer to Shajar as the feminine sultana, contemporary coins indicate she assumed the masculine sultan—first as partner in lordship as regent, then as sole lord of the realm—a title unchallenged by those loyal to her.25

Looking all the way back to the 1st century CE, we have evidence of women occupying every role required within military service, combat facing et-al. But more than that, we can witness the clear influence and authority women were able to access. An authority recognized across communities, across realms, far into the recesses of neighboring territories, far more than we give historical credit for.26

In 40 CE, The Trưng sisters, Trưng Trắc and Trưng Nhị, led a rebellion against the first dominating rule of Han China in Vietnam. It would take the Han army three years to suppress the sisters’ influential rebellion, in which time the Chinese army would lose up to potentially half their soldiers to battle and battle incurred illnesses.27

As an abolitionist feminist who doesn’t believe in the death penalty, I am not advocating that war be more accessible, nor am I advocating for war. Any government that incites or supports war is inevitably governing contrary to human interest.28 I simply find myself unwilling to ignore your very obvious propaganda and erasure attempts.29

I end with this, mister secretary: While you and the manosphere that earned you you're current position perpetuate the idea of women in the military as a DEI initiative born of modernity, I will continue documenting the lived realities of women in world history who not only possessed a very real and very practical power within their own times, but women that achieved far more chivalrous feats than yourself within the theater of war. The folders are overflowing.

May we all intentionally move through this world in a way that recognizes one another’s humanity,

Writer’s note: I talk about gender rules and gender roles within this essay — none of me is upholding patriarchal gender roles by highlighting the dichotomies of the past. Trans rights are human rights. If knowing I believe such means you can’t be here any longer, then don’t be here. But I do hope you will continue learning how these gender rules/roles are completely man made and oppressing your truest-self now as much as they did our counterparts in the medieval world. Sending love. 💜

To keep an eye on:

Thank you, for tracking this.

Matilda was of course exceptional, but Matilda’s exceptional qualities go far beyond her participation in the theater of war and lie within her fierce conviction of self amidst patriarchal nonsense and relentless misogyny.

https://www.cnn.com/2024/11/14/us/military-women-pete-hegseth-defense-secretary/index.html

https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3580676/defense-department-report-shows-decline-in-armed-forces-population-while-percen/

Nicholas, K. S. (1999). Countesses as Rulers in Flanders. In T. Evergates (Ed.), Aristocratic Women in Medieval France (pp. 111–137). University of Pennsylvania Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt3fhtdn.9

Evergates, T. (2023). Blanche of Navarre, Countess of Champagne. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780415791182-RMEO205-1

Sjursen, K. E. (2010). Peaceweavers' sisters: Medieval Noblewomen as Military Leaders in Northern France, 1000–1337

Livingstone, Amy (2010). Out of Love for my Kin: Aristocratic Family Life in the Lands of the Loire, 1000-1200. Cornell University Press

Sjursen, K. E. (2010). Peaceweavers' sisters: Medieval Noblewomen as Military Leaders in Northern France, 1000–1337

Duby, Georges (1997). Women of the Twelfth Century.

I use lordship here as a delineation of power associated with significant landholding, not in regards to a gendered title specific to men. Lordship, in terms of benefiting those that held power, was fulfilled by a community of people.

Sjursen KE. Weathering Thirteenth-Century Warfare: The Case of Blanche of Navarre. In: Gathagan LL, North W, eds. The Haskins Society Journal 25: 2013. Studies in Medieval History. Haskins Society Journal. Boydell & Brewer; 2014:205-222.

Powers, Eileen (1975). Medieval Women.

Kelly, Amy (1950). Eleanor of Aquitaine and the Four Kings.

As made evident by her collection of queen’s gold:

Kristen Geaman, “Queen’s Gold and Intercession: The Case of Eleanor of Aquitaine,” Medieval Feminist Forum, 46:2 (2010): 10–33

Male lord

Eileen Power discusses how those of the lower caste would be accustomed to working alongside women daily in Medieval Women. The above references offer insight into the nobility which matches this sentiment and the below is one example of it in the church. Other great sources to find similar examples:

Goldberg, P.J.P. (2010) Women, Work, and Life Cycle in a Medieval Economy: Women in York and Yorkshire c.1300-1520. Oxford University Press.

Harwood, Sophie (2022). Medieval Women and War: Female Roles in the Old French Tradition (Material Culture and the Medieval World). Bloomsbury Academic.

Ed. Tanner, Heather J. (2019) Medieval Elite Women and the Exercise of Power, 1100–1400 Moving beyond the Exceptionalist Debate.

Ed. Anderson, Bonnie. Zinsser, Judith. (1999) A History of Their Own, Volume One: Women in Europe from Prehistory to the Present. Oxford University Press.

DeAragon, R.C. (2019). Power and Agency in Post-Conquest England: Elite Women and the Transformations of the Twelfth Century. Medieval Elite Women and the Exercise of Power, 1100–1400.

Sumption, Jonathan (1999). Trial by Battle: The Hundred Years War I. University of Pennsylvania Press

Ibid. This series is a pool of resources, but I found it interesting the willingness to exhibit Philippa’s intercessor roles far more than her documented power roles.

Strickland, Agnes. (1898) Lives of the queens of England, from the Norman conquest; comp. from official records and other authentic documents, private as well as public. Preceded by a biographical introduction by John Foster Kirk v.2

Sumption, Jonathan (1999). Trial by Battle: The Hundred Years War I. University of Pennsylvania Press

Katrin E. Sjursen (2015). The War of the Two Jeannes: Rulership in the Fourteenth Century

Hamilton, Bernard. Women in the Crusader States: The Queens of Jerusalem (1100-1190) - https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/E7198BD7B384CC7E2380A46B3F14CFF1/S0143045900000375a.pdf/div-class-title-women-in-the-crusader-states-the-queens-of-jerusalem-1100-1190-div.pdf

Ruggles, D. Fairchild (2020). Tree of Pearls: The Extraordinary Architectural Patronage of the 13th-Century Egyptian Slave-Queen Shajar al-Durr

Ibid.

(14C example here, 1C example is up next!) Friossart’s Chronicles often records Edward III treating with Jeanne de Montfort and other Breton noblewomen, an action that neither Friossart nor La Bel indicate as anything out of ordinary behavior. Men of the time fully recognized women’s practical contemporary power.

The Fourteenth Biography of Ma Yuan in the Book of the Later Han Dynasty

Tuchman, Barbara (1984). The March of Folly

In regards to women being too meek and timid to lead nations in the modern world and medieval one alike - A quote from Dubey, Oeindrila. Harish, S.P. Queens (2015):

Using this approach, we find that polities ruled by queens were 27% more likely to participate in inter-state conflicts, compared to polities ruled by kings. At the same time, queenly reigns were no more likely to experience internal conflicts or other types of instability.

We explore two theories of why female rule may have increased war participation over this period. The first theory suggests that women may have been perceived as easy targets of attack. Female rule was sometimes virulently opposed on exactly the grounds that women made for weak leaders, who were incapable of leading their armies to war. This perception—accurate or not—could have led queens to participate more in wars as a consequence of getting attacked by others.

As a female veteran, I am thankful for this piece. As a female writer, I am awed by the deep dive into historical research! Incredible piece, and thanks for keeping eyes on the removal of our female warriors. The story broke early this morning that yesterday, the just-fired Coast Guard Commandant was given mere hours to vacate her residence, being forced to leave most of her furnishings and personal belongings. She said she had to “stay with friends” last night… an admiral! Couch surfing! Because of the insecure men in DC. I predict we’ll see more of not only firing/“relieving of duty” of female women in leadership but the additional humiliation tactics, unfortunately.

Thank you, Kate - history lessons like these are more important than ever. Can I also recommend to your readers Pamela Toler’s Women Warriors? A stellar look at how women have *always* been warriors, across the globe.

https://bookshop.org/p/books/women-warriors-an-unexpected-history-pamela-d-toler/9000139?ean=9780807028339