Elizabeth Woodville, Divorcing from the Patriarchy: The projectile protestations of George Plantagenet

A reorganization of realities pt 2

TW: r*pe, violence

Patriarchal bias, often unconsciously consumed, masquerades as necessary adjectives to inform the reader, however accurate or inaccurate these words may be, they are often more informative of the author’s own paradigm than that of the character they are trying to retrospectively shape from contemporary sources. For example, in Desmond Seward’s The War of the Roses he writes of Margaret Beaufort, that “although only 13 and very small for her age – she would grow up to be a tiny little woman – Margaret was pregnant. Regardless of her childishness and pitiful size, Edmond had insisted on consummating the marriage, probably from avarice rather than brutality, if he could father a child on her, then by law he would be guaranteed a life interest in her Estates.” As if a 25-year-old forcing a 12-year-old to experience repetitive forced intercourse and the subsequent childbearing and rearing isn’t inherently cruel and brutal. Greed doesn’t negate brutality, it begets it. The internalized misogyny of the author allows him to see the man’s greed as inherent, not imposed, whereas the girl’s suffering is an unfortunate necessity of the times.

“When greedy consumption is the order of the day, dehumanization becomes acceptable. Then, treating people like objects is not only acceptable but is required behavior.” – bell hooks

It wasn’t until women widely gained access to secondary and collegiate education throughout the 19th century that we saw a shift to women-centric histories; placing women back into their own stories, whilst uncovering their hidden, often intentionally erased, influence. Though female historian and authorship are on the rise, “the academic field of history remains highly male dominated... A conservative academic culture and a lack of willingness to problematise male dominance in the field can take much of the blame for this.”1 The antiquated expectations of historical text are generationally recycled and any attempt to highlight a shared human experience between then and now is rebranded as anachronistic from male historians who directly benefit from the unseen patriarchal puppet master. Much like men’s rights activists, the historical genre has largely been unwilling to name the invisible societal and political force behind the strict adherence to an invisible rulebook. We glamorize and romanticize the chivalric code, rebranding it as something sexy instead of labeling it for what it was: the foundation modern day patriarchy was built upon. Late 20th century male authors will faithfully deem Elizabeth Woodville as the destructive force behind the Yorkist dynasty without unpacking how the men around Elizabeth were ultimately responsible for their own decisions.

The patriarchy is predicated on men willingly upholding unachievable expectations over themselves and other men daily, trading their own internal peace and personal integrity for a semblance of control over a relatively unfulfilled life. Instead of stepping back to inspect the harmful society which white supremacist patriarchal structures have created for all, including themselves, the laissez-faire attitude of ‘that’s just the way it is’ is adopted and reinforced. If modern male historians allowed for the ownership of actions to fall upon the one taking action, the history of the world as we know it would have to be rewritten. However, we know this ownership will be slow to be acknowledged just as we know patriarchal historians will easily see the worst of humanity in women and extend perpetual grace to the actual antagonists of most histories.

“Passive male absorption of sexist ideology enables men to falsely interpret this disturbed behavior positively. As long as men are brainwashed to equate violent domination and abuse of women with privilege, they will have no understanding of the damage done to themselves or to others, and no motivation to change.” - bell hooks

Seward, publishing in 1995, writes “[Elizabeth Woodville] had refused to sleep with Edward even when he drew his dagger, telling him that while she might be too base to be a king’s wife, she was too good to be his harlot.” Although this account highlights Elizabeth’s virtuousness and strength of will, defying the advances of a persuasive, knife-wielding rape-inclined king, Seward quickly accepts the misogynistic trope of the past without identifying how his own words often conflict with the ascribed adjectives used throughout his work. He describes Elizabeth as “a cold, grasping woman, her attempts to promote the Woodville family fatally undermined the Yorkist dynasty” and quickly follows up with confidentially asserting that she was “an arrogant lady with greedy kindred.” Seward, continually commenting on Elizabeth’s famed beauty, laughably asserting his own attraction to the long-dead queen, created a sexually appealing antagonist all within the first six pages of his book, without once looking at the lopsided power dynamic at play nor the inherent biases plaguing the histories he referenced. if Elizabeth was in a position of profuse refusal, that means Edward was in a position of aggravated proposition, that coupled with the fact that he was her anointed king and held immense power over this new widow hardly highlights a ‘grasping or arrogant’ woman, but a desperate one with very limited options.

The only character marked with greediness in Seward’s depiction of Elizabeth and Edward’s meet-cute is our jovial knife-wielding monarch. The paradigm most white-male historians are unable and unwilling to view women’s experience through is that of the victim of oppression; the unconscious patriarchal bias dictates that secondary status is inherent, not imposed. Acknowledging the imposition would be to acknowledge a defined oppressor, but as they so collectively love to chant each time morality flaws are pointed out, it’s not all men. Seward can easily acknowledge women’s marginalization, “most ladies were unable to play anything other than a passive role during the Wars of the Roses,” but is unable to see the intentionally imposed and rigid adherence of said marginalization and the unconscious way in which it shapes his false reality of women.

Elizabeth was Edward’s powerless subject, put in an impossible power-dynamic situation due to a man’s belief that she was an object meant for his consumption and gratification much like we saw above in the case of Margaret Beaufort. If Elizabeth refused the king, the lifesaving pardons her brother and father received could have been withheld and attainders delivered in their place. Her sons’ inheritance could have been granted to her greedy mother in-law or diverted to Lord Hastings or the crown to use as assets. Elizabeth’s livelihood became wholly dependent on what the new king did next, and making the best of a bad situation has forever earmarked her as a greedy upstart. From the beginning she not only existed within an oppressive state but also navigated the most extreme power-imbalance imaginable. As white men offer their academically informed opinion, their lack of empathy and understanding of systemic oppression is masked as pretentious insight into a world they have never experienced and willfully misrepresent. They are quick to identify that the patriarchal nature of the times more-often-than-not left women’s perspective undocumented, yet still have the audacity of man™ to posit how women felt and the motivations for their operations.

When we last left Elizabeth in the first essay of this three-part series, she had been cast as haughty and contemptuous for adhering to traditional standards at her own coronation, yet the reported tone was strongly influenced by a heavily biased source: Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick. Seward, staying true and never deviating from the stronghanded historical bias writes “no doubt such silence was customary at the English court in the fifteenth century and previous consorts had been served in silence, but they had been kings’ daughters. Everyone present was aware of the queens ‘low extraction’ and that she had been a woman of the bedchamber.” Seward mentions the queen’s low birth, yet even by his own account we see these same strict adherences at ceremonies within the merchant class, which was a lower status than that of a Barony, the peerage her father held at the time. It was a cultural practice that Elizabeth would have been aware of and expected/raised to follow. Imagine the contempt contemporaries and historians alike would have had if she instead turned her nose up against said traditions, it too would have provided immediate validation of her unworthiness. The patriarchy creates a no-win situation for women, and Elizabeth was all too familiar with this.

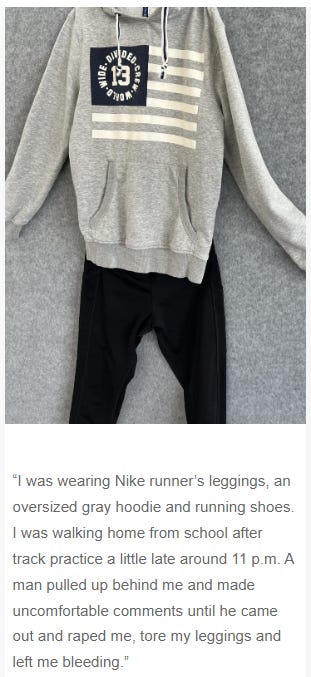

The bias of perceiving Elizabeth through this one lens dilutes the greed of the men around her and serves as a productive way to perpetuate the patriarchally imposed idea that women are inherently sinful and responsible for men’s sins, thus furthering the strict dichotomy that women can either be wholly good and unspoiled like the virgin mother, or wholly depraved like the sensual seductress. Paul Murray Kendall, hailed a Ricardian hero, writing in 1955, referred to Elizabeth as ‘vengeful,’ ‘coldly furious, and ‘insatiably ambitious’ implying that much of Edward’s decisions were based on her greed, yet no contemporary evidence is provided nor is there recognition that Edward possessed his own agency and as anointed king, had the ultimate power. As Alison Weir points out “late medieval monarchy was a highly personal system of government: in this period kings ruled as well as reigned, and they wielded vast power.” Medieval misogynistic opinions are touted as fact without an inspection of the propagandized source or the severe power imbalance at play. This is the very same bias that allows for the continuation of disgusting and dehumanizing arguments such as “what was she wearing?” and the shifting of blame from perpetrator to victim. It’s the steppingstone that modern day victim blaming found a foothold within.

Much of how Elizabeth is perceived within the histories is largely impart to Edward’s younger brother, George Plantagenet, and the extensive propaganda campaign him and his father-in-law, Warwick, employed between 1469 up until George’s death in 1478. What transpired over the nine years between 1469 to 1478 was a devastating continuation of a civil war that started from a need to stabilize the monarchy and was resumed out of greed and misogynistic hostility. Historians will quickly site the continuation of this bloody feudalism due to the promotion of the queen’s family, but when the evidence of the advancements received by Warwick and George, respectively, are weighed against the advancements of the Woodville family with consideration of loyalty to Edward IV’s reign, the Woodville family’s gain was a parallel outcome of loyal service and affection. Too often it is lost upon historians that Warwick’s greed and malice were only intensified by the obvious reverence the Woodville family, Edward, and court felt towards Jacquetta and her documented power and influence; a reaction that modern feminists can surely relate to: watching a man react in all of the worst ways when you assert your agency, boundaries, and voice.

Perpetually dissatisfied by his own status, George shared in Warwick’s revulsion of the Queen’s blood. Motivated by greed for the throne, having tasted power as heir-apparent and highest peer for the first nine years of his brother’s reign, much of George’s actions teeter between sycophantic and narcissistic. Ultimately his actions led to an early demise, being just 29 years old when he was condemned to death for treason, which of course, is blamed on Elizabeth though he alone is responsible for his actions, relentlessly erring on the side of greed time and again.

In a rebellion incited by Warwick and George’s faction, a manifesto and letter circulated that called for the removal of the Queen’s family from council and influence, specifically mentioning Jacquetta, the only woman named in any such manifesto of the time. Indicative of Jacquetta’s power and authority, the letter also maligned Edward’s mother, Cecily Neville, indicating that Edward was not the true heir of Richard, Duke of York, but a bastard conceived through adultery while the family was stationed in Rouen. The misogyny is clear, and the objectification of the women included is a necessary outcome of the men’s greed, portrayed within the histories as a product of their environment rather than a character flaw of either man.

As K.R. Dockary highlights in The Yorkshire Rebellions of 1469, “the manifesto seems, in many respects, very much in the tradition of such documents in the later Middle Ages. Certainly, it does include all manner of grievances felt by ordinary folk in England by 1469, most notably heavy taxation, the prevalence of lawlessness and the misuse by great men of their power in the provinces. In these respects, the manifesto does indeed have all the appearance of an authentic rebel petition (such a petition as the Yorkshire rebels in 1469 might well have produced). Yet there are strong indications, too, that it might be essentially the work of Warwick the Kingmaker and his discontented aristocratic supporters George Duke of Clarence and George Neville Archbishop of York. Specifically, the manifesto indicts Edward IV’s favour to the family of his own Queen (the Woodvilles) and his advancement of men like William Herbert Earl of Pembroke and Humphrey Stafford Earl of Devon. There clearly is a propaganda element about these references (as about the rest of the document), but they do very much reflect, as well, the personal and political grievances of Warwick the Kingmaker. And, there can be no doubt, the letter and manifesto together were intended to stimulate support for Warwick and Clarence in south-eastern England when they arrived there (as they intended to do) a few days later.”

Historian’s will cite the Woodville family’s ‘known greed’ through one instance concerning a tapestry and ransacking of a home yet will ignore the immense greed required to plunge an entire country into deadly civil war in order to place the monarchy tangentially in the hands of Warwick. The obviously biased manifesto then becomes proof of maleficence displayed by the Woodville’s instead of evidence of a strategic ad hominem attack utilized by George and Warwick. During the battles that followed the release of the manifesto and reinstitution of Henry VI upon the throne, Elizabeth’s brother and father were captured and promptly beheaded without a trial in the name of treason, yet their only fault had been staunchly defending the anointed king. While Elizabeth’s father and brother were meeting their gruesome fate, Elizabeth’s fierce mother Jacquetta was being accused of witchcraft.

Having witnessed the success of a faction downfall when Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, lost all power after his wife, Eleanor Chobham, was accused of witchcraft in 1441, Warwick and George sought to discredit, murder, or malign the entire Woodville stock in one fell swoop. The recycled nature of both the witchcraft accusation and the language used within the manifesto and letter remind me of what creator Lolaokola recently said in a reel: “the reason women don’t give a shit about what men think about anymore is that we already know what they are going to say. If they don’t like your opinion, you’re ugly. If you’re not ugly, then you’re fat. If you’re not fat, then you’re a hoe. If you’re not a hoe, then you’re going to die alone. That’s it. It’s tired.” The patriarchal rule under which Jacquetta and Elizabeth lived within dictated that reputation was more important than actual behavior, thus allowing for the continued, and tired, character assassinations both women still receive today. Medieval equivalent to ugly, fat, hoe was a witchy hoe.

Though Jacquetta was able to overturn and beat the charges, it is a charge still strongly associated to her and her royal daughter. The characters of these women are hidden behind a dense layer of patriarchal propaganda, yet much like today, all women are “linked by the common thread of misogyny” as Scotland’s first minister Nicola Sturgeon said within her 2022 apology to parliament. Speaking on the charge of witchcraft, Sturgeon said “those who met this fate, were not witches, they were people, and they were overwhelmingly women. At a time when women were not even allowed to speak as witnesses in a courtroom they were accused and killed because they were poor, different, vulnerable, or in many cases just because they were women, it was injustice on a colossal scale, driven at least in part by misogyny in the most literal sense: hatred of women.”

George’s hatred of women allowed him to enlist ad hominem campaigns against the women in his life, and the socialized misogyny of patriarchal historians continued the crusade and touted it as evidence for the righteousness of the men’s behavior as opposed to the attestation of their malversation. The patriarchal persecution of Elizabeth continues far beyond her life, but what she showed us was that the fierceness and bravery of her mother was inherited, and though her thoughts and true feelings weren’t deemed important enough to record, her actions show us who she truly was.

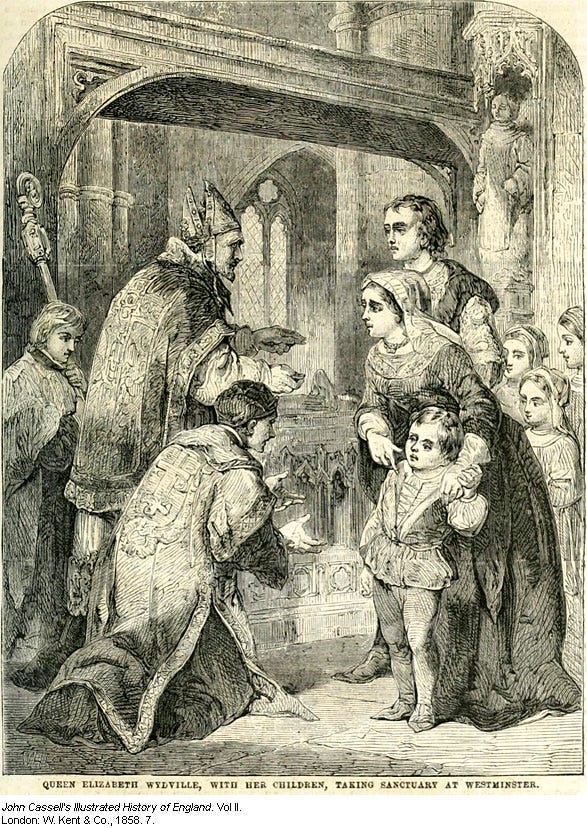

“In the middle of the night of 1 October 1470 Queen Elizabeth Woodville, who was now eight months pregnant, took her three young daughters down to the dock at the Tower of London. Here, she secretly took a barge down the River Thames to Westminster Abbey, where she was met by her mother, Jacquetta of Luxembourg.”

– Royal Witches, Gemma Hollman, 2019

“And so, after continuing much shot of guns and arrows a great while, upon both parties, the Earl Rivers, that was with the Queen, in the Tower of London, gathered unto him a fellowship right well chosen, and habiled, of four or five hundred men, an disused out at a postern upon them, and, even upon a point came upon the Kentish men…and mighty laid upon them with arrows, and upon them with hands, and so killed and took many of them, driving them from the same gate to the water side.”

– The Historie of the Arrivall of King Edward IV, 14712

“Edward IV had suffered insurrection, disloyalty, imprisonment, and exile, while Elizabeth had experienced the murder of her father and brother, the birth of her son in sanctuary, and had been besieged in the Tower while her husband hazarded his life in battle. There is no evidence that, throughout all this, she behaved with any but a queenly dignity which won the admiration of loyal contemporaries. No writer saw fit to criticise her, and William Alyngton, the Speaker of the Commons, ‘declared before the Kinge and his noble and sadde counsel, thentente and desyre of his Comyns, specially in comendacion of the womanly behaveur and the greate constance of the Quene, he beinge beyond the See.”

- Elizabeth Woodville: Mother of the Princes in the Tower, David Baldwin, 2002

https://kjonnsforskning.no/en/2015/09/history-still-men

Susan Higginbotham, Woodvilles: The Wars of the Roses and England's Most Infamous Family