Elizabeth Woodville, Divorcing from the Patriarchy: the Warwick Lens

A reorganization of realities part 1

“As she walked out into the cool morning air, Margaret Pole could therefore have reflected that, although she was due to be beheaded that morning, she would at least die wearing new shoes.”

As a woman reader of history there are so many moments I’ve been stopped in my tracks by the force of the misogyny radiating from the page. It’s like that mid-century lamp in the corner of a distant relative’s house that sparks in the outlet and has a four-foot heat-radius: dangerous yet left to sit, serving an illusionary role. The minimization, the villainization, the continual unconscious blame on women for fulfilling roles they were forced to perform is generationally constant and dangerously impactful, yet it too often resurges as if it’s an original thought. The opening line to this essay was copyrighted in 2014 by one of the most popular British medievalists of our time. Though this particular historian does in fact point out and name the brutality of patriarchal norms of the 15th and 16th centuries, the irony is lost upon him that his unconscious biases ultimately shaped his assertation of women’s internal drivers.1

“Passive male absorption of sexist ideology enables men to falsely interpret this disturbed behavior positively. As long as men are brainwashed to equate violent domination and abuse of women with privilege, they will have no understanding of the damage done to themselves or to others, and no motivation to change.” - bell hooks

Margaret Pole was 67 years old when she was butchered at the executioner’s block. A novice death-dealer with a dull blade purportedly needing upwards of 12 blows to complete the deed. But before she met her demise whilst admiring her pretty new shoes, she was a niece to kings, and cousin to the princes in the tower and Elizabeth of York. She survived five monarchs, lost her father to a barrel of malmsey wine via a traitor’s death, was one of the wealthiest aristocrats of 16th century England in her own right, and was potentially one of the few people who could honestly answer ‘did they or did they not?’ in regards to Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon’s marriage consummation. Yet she is reduced to a lighthearted quip to satiate the patriarchy’s requirement for the constant belittling of women. The ultimate proverbial butt of the joke.

This reduction of Margaret’s character isn’t an isolated incident regarding women’s representation within the histories of the Middle Ages. Because women were forced into roles that the patriarchy deemed insignificant meant that they were often secondary characters, placed into the margins or completely overlooked. Stripped of their cultural and societal impact, ultimately discredited as contributors while being held to the highest standards of moral behavior and marital support. Elizabeth Woodville, Margaret’s aunt by-law, is another woman whose historical context and identity is enmeshed into the roles she served in the lives of the patriarchs around her.

Our paradigms are unique to each of us. We are all beautifully individual yet startlingly similar. That is the human condition. Yet the patriarchy addles those lenses, blurring the lines between human behavior, gender roles, and individuality. Because most of us still live in patriarchal social structures and are forced to participate in the very systems that oppress us, we’re still viewing women how the patriarch wants us to see them: frivolous, inherently depraved, and vacuous. It is too easy to read materialism into a 67-year-old woman’s character without questioning it, but would Margaret Pole truly have been thinking about her shoes on the day of her execution after the live she led? Assuredly not.

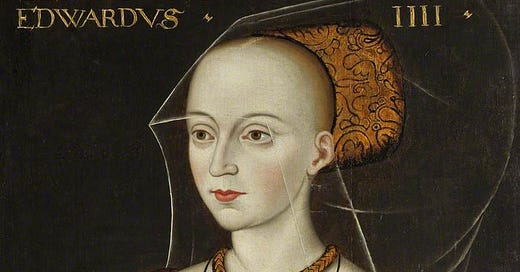

Divorcing from the patriarchy requires us to reflect on the impact of it within our own lives while also requiring us to investigate why we think the way we do, especially about personal values shaped by our collective history. Elizabeth Woodville was the commoner queen of England from 1464 to 1470, and then again from 1471 until 1483 when her husband, Edward IV, passed away. Elizabeth, eldest daughter of Jacquetta of Luxembourg and Richard Woodville, is known in history strictly through the roles she held in service to the patriarchy: daughter of an upstart knight, wife to Edward IV, mother to the princes in the tower and Elizabeth of York, rival of Richard Neville, earl of Warwick, George Plantagenet, duke of Clarence, and Richard Plantagenet, duke of Gloucester, and catalyst of the Plantagenet dynastic destruction. The caricature that has been painted of her is one of hollow beauty, haughtiness, and over-reaching. Would Elizabeth even recognize herself if she read her own histories?

Unpacking Elizabeth and placing her back into her own story requires us to examine why she is known the way she is, investigating the various ways in which the patriarchy impacted her life. Elizabeth’s family were considered vulgarian upstarts, reaching far beyond their status whilst tainting the purity of the noble bloodlines. However, Elizabeth hadn’t set out to become queen. She was first married to a man named John Grey. The Greys, a local-to-her gentry family, would have been a more appropriate station-pairing to that of her family’s own patriarchal title of baron Rivers.

Most likely born sometime in 1437, Elizabeth’s upbringing was similar to that of her well-documented noble contemporaries, just at a much smaller luxury-scale. As a girl, she would have learned how to fulfill the patriarchal roles seen fit for her: wife and mother. But her family taught her much more than just her roles of servitude. Unlike most, Elizabeth was born into a seemingly respectful love union. Her mother, Jacquetta, was at one point the first lady of the English court, married to John, Duke of Bedford, brother to king Henry V and uncle to the sitting monarch, Henry VI. When John died, just two years into their marriage, Jacquetta was left a wealthy widow at the age of just 19. Being a wealthy single woman in the Middle Ages was a precarious position, see: Eleanor of Aquitaine’s plight to marry Henry II in 1154. Going against a decree from Henry VI, Jacquetta married a squire of her late-husband’s household, the handsome Richard Woodville, for love.

This match of Jacquetta and Richard would be Elizabeth’s first err in the eyes of her later rivals for a myriad of reasons. Due to Jacquetta’s station as dowager duchess, she became a lady-in-waiting and close friend to Margaret of Anjou, Elizabeth’s regal predecessor. The Woodville family, friends and staunch allies to the Lancastrian cause early in the cousin’s war, were loyal to the anointed king and his steadfast queen. Richard Woodville, Elizabeth’s father, was a distinguished knight and military mind, prominent in Henry VI’s fighting armies. During this time, Henry’s cousin, Richard duke of York, was stoking rebellion in the name of good governance, for as pious as Henry VI was, he wasn’t a strong monarch for feudal England; thus, ensuing the civil disturbances later dubbed the War of the Roses.

The men fighting for the Yorkist cause made their grievances against Richard Woodville and his family known when they kidnapped Richard and Anthony, Elizabeth’s eldest brother, in the early hours of the morning and held them prisoner in Calais, berating them, stating that Richard was a “knave’s son, that he should be so rude as to call him and these other Lords traitors, for they should be found the king’s true liegemen, when he should be found a traitor.” Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, told Richard that it wasn’t his place to have “such language of Lords” as “he himself [Woodville] had been made my marriage.”2 Ironic given Richard Neville’s title Earl of Warwick, one of the most illustrious titles of English nobility, was granted to him due to his own marriage, as he wedded the heiress of multiple hefty inheritances. Ultimately, these Yorkist men who hurled insults at Elizabeth’s father and brother were to win the crown, placing Richard duke of York’s eldest surviving son, Edward, onto the thrown.

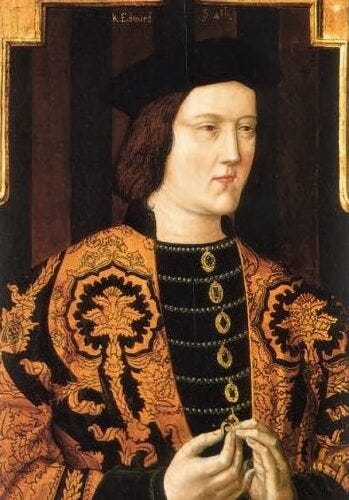

Warwick, having been vital in the usurpation of Henry VI and installment of Edward IV, was a major benefactor from the goodwill of this new, young, gracious, peace-seeking king. Procuring more profitable property and formidable positions, Warwick was surely envisioning a life of luxury and favor ahead, for as a bachelor king’s greatest advisor and champion, his blessings would now seemingly be in perpetuity. Though he would never wear the crown himself, his triumph as an advisor ensured Edward’s trust in him was unwavering. Warwick’s heavy-handedness in English politicking was well known in the early years of Edward’s reign, so much so that the Governor of Abbeville wrote in a letter to French king Louis XI “they have but two rulers, M. de Warwick and another whose name I have forgotten.”3

Edward’s secret marriage to Elizabeth divorced him from Warwick’s overreaching hand, no longer held in the highest council, and excluded from weighing-in on one of the most impactful decisions, Edward asserted his dominion over Warwick and domestic decision-making by marrying the queen of his choosing. Edward did this without the knowledge of the lords of the land, a sentiment that would later be hurled at the young couple, though if viewed holistically, can be seen as Edward’s first real step into owning the power of kingship that was now his, and his alone. “Edward’s actions highlight the personal nature of his rule, the strength of his personality and his unwillingness to follow anyone else’s rules.”4 Edward’s strength of personality was matched in Elizabeth and while she was secretly marrying the king, Warwick was in France negotiating a magnolious match with Bona of Savoy, hoping to win favor with both the French and English crowns as a reward for his matchmaking endeavors. Warwick was surely disappointed when realization dawned that his efforts were for naught.

“If the intention behind the work is to seek recognition and power then you are setting yourself apart from others as a way of trying to feel connected to them.” - bell hooks

With the marriage to Elizabeth came a slew of brothers and sister’s by-law for the new king. This allowed Edward to curry royal favor and encircle himself with faithful family, marrying his queen’s siblings into the English nobility and entrenching his court with reliable relatives which he could impose his Arthurian ambitions upon. One such pairing was that of Elizabeth’s eldest unmarried brother, John, which “caused no little scandal when he wed the elderly Catherine Neville, dowager Duchess of Norfolk, the Earl of Warwick’s aunt…John was probably little more than twenty while his thrice-widowed bride was in her sixties.”5 This very apparent financial grab by Edward via the Woodville’s was yet another in a long list of perceived slights against the Warwick faction.

Due to Warwick’s patriarchally socialized thinking that power is a zero-sum game, the rise of the Woodville’s meant the fall of the Warwick’s. As made evident by Warwick’s later actions and subsequent infamy, the patriarchy does not want you to put it under a microscope. If we stop, pause, and reflect on the ways in which the patriarchy harms us all, it wouldn’t have a single ally, but its existence is predicated upon hurt men hurting other men and perpetuating endless trauma responses which then shape all our lived realities. When Edward wed Elizabeth, “Warwick in particular appears to have been disappointed, having been charged to conduct negotiations for the hand of Bona, and worse, to not have been in Edward’s confidence… The earl was ‘greatly displeased’ and ‘great dissension’ arose between him and the king, to the effect that ‘they never loved each other after. Warwick and his friends, who helped to make him king, he no longer regarded at all. Because of this Warwick hated him greatly and so did many noblemen.’ The Great Chronicle adds that Edward’s marriage ‘kindled after much unkindness between the king and the earl [and] much heart burning was ever after between the earl and the queen’s blood so long as he lived.’ It was also a personal insult to the earl: a public rejection of his French aspirations and a break in their previous close conspiracy.”6

Though Edward fulfilled societally held kingly ideals with his reportedly handsome, larger-than-life, gregarious presence, in all reality he was a usurper, having won the thrown by forcibly removing an anointed king. To assert his righteous sovereignty, he employed strict Arthurian chivalric codes of conduct for all members of his court and utilized luxury to project majestic authority. As a medieval queen consort by her king’s side, Elizabeth’s role was twofold, both roles of course being in strict servitude to the patriarchy. As Amy Licence so aptly writes, “maternity was considered the highest aspiration for a woman, defining herself as a functioning part of, and contributor to, the patriarchal system.” Elizabeth was expected to provide Edward with an abundance of heirs which would in turn enforce the legitimacy of his Yorkist reign. Providing a male heir would cement Elizabeth’s position as queen, and though their first three children together were girls, the couple deviated from patriarchal expectations and grandly celebrated the safe issue of their daughters with opulent christenings, peacetime allowing. With a mother-by-law in Jacquetta and a wife in Elizabeth, Edward had a lived experience of the inherent worth those three baby girls held and the power they could bring forth if nurtured.

“Another component of queenship was intercession. In some political situations, it was injudicious for the king to appear to yield or capitulate. A queen had the ability to intervene and moderate the king’s policies without him losing face.”7 If a queen interceded beyond the undefined, inconsistent patriarchal expectation, she was cast as unwomanly, even animalistic such as we saw with Margaret of Anjou. If a queen was perceived as not interceding enough, her husband’s brutality was blamed on her lack of action and intercession. “Boys are never expected to serve as guardrails for girls, in the way that women are expected to become the equivalent of a human fence for men’s distasteful impulses and proclivities. Isn’t it curious that girls are seen as in need of protection, when they’re the ones burdened with the incalculable task of protecting men from themselves?”8 Half a millennia later, girls and women are still being held accountable for men’s depravity.

It is within this context we encounter Elizabeth’s most attributed characteristic, one that plagues modern and medieval biographies alike: haughtiness.

Because England was deprived of a royal wedding, Edward was determined to enforce his legitimacy through the grandeur of Elizabeth’s coronation. Elizabeth was expected to adhere to her husband’s strict Arthurian behavioral codes to demonstrate pomp and dominion, and though this pompous behavior was expected at some level by all higher nobility, it was weaponized against Elizabeth. “A Bohemian gentleman, Gabriel Tetzel, was visiting London with his master Leo Rozmital, and others, and was invited to observe the service and the banquet which followed,” writes David Baldwin, one of Elizabeth’s more modern historians. Tetzel wrote: “When my lord and the Earl [Warwick] had eaten, the Earl conducted my lord and his honourable attendants to an unbelievably costly apartment where the Queen was preparing to eat. My lord and his gentlemen were placed in an alcove so that my lord could observe the great splendour. The Queen sat alone at table on a costly golden chair. The Queen’s mother and the King’s sister had to stand some distance away. When the Queen spoke with her mother or the King’s sister, they knelt down before her until she had drunk water. Not until the first dish was set before the Queen could the Queen’s mother and the King’s sister be seated. The ladies and maidens and all who served the Queen at table were all of noble birth and had to kneel so long as the Queen was eating.”9

The events that Tetzel documents are that of ostentatious pomp, yet as queen consort, Elizabeth wouldn’t have been responsible for the planning and execution of her own coronation. She would have been expected to behave in accordance with Edward’s wishes, and part of the mysterious majesty he was trying to project was the glory and righteousness of his reign, aligning these through ritualistic, ceremonial behaviors. This image of Elizabeth, a commoner sat on a golden chair, demanding the high nobility to kneel and attend to her has marred Elizabeth’s true character from being read within the histories. Though Tetzel’s account is cited as firsthand, it’s safe to assume some, if not all, of his account is hearsay and heavily influenced. As adherent to Edward’s code of conduct, formal dining occasions such as this demanded that those participating be separated, seated, and served by rank. Tetzel himself admits that Warwick was their host and tour guide, and with Warwick’s well-documented propensity to illicit negative feelings towards the queen’s blood through verbal assault, it’s likely Tetzel’s interpretation of the event was influenced by Warwick’s personal biases and ambitions. Tetzel’s master, Lord Rozmital, sat and dined with Warwick during the many hours of this feast, potentially negatively discussing the very subject matter they were there to celebrate.10

As author Matt Lewis remarked about Elizabeth’s father-by-law, “I’m always wary of these kind of Hollywood style one dimensional figures from history. They’ve generally been flattened out to serve some moral purpose in the story and giving them back those extra dimensions can often reveal a much more interesting story.” Elizabeth’s coronation is often the first introduction a historical reader has with her character outside of her scandalous, secretive wedding, yet the whole affair is heavily blurred through the lens of a personal, unidentified patriarchal bias.

Though modern historians can site Warwick’s greed and ambition, identifying patriarchal norms through exhibited ideals and behaviors, they fall short in identifying how that same social and political system shapes and informs their very perception of the wholeness of women in the Middle Ages. Warwick’s rejection and subsequent anger are identifiable and relatable to the modern male historian. “Real men get mad. And their mad-ness, no matter how violent or violating, is deemed natural – a positive expression in patriarchal masculinity.”11

Elizabeth’s early years as queen were deeply impacted by Warwick and his treachery, yet this passionate, educated, brave woman was not dissuaded from claiming and employing her worth and influence. The patriarchal histories have tried to erase Elizabeth’s wholeness. It’s time for it to be realized.

Next up: Elizabeth Woodville, Divorcing from the Patriarchy: The projectile protestations of George, duke of Clarence. A reorganization of realities pt 2.

Page 2, The Wars of The Roses, by Dan Jones - I personally am a huge Dan Jones fan, but the reality of being a woman medievalist is the misogyny wasn’t left in the 16th century. I' highly recommend subscribing to Dan’s Substack and listening to his newest podcast, where he does indeed name and blame the patriarchy.

Page 55, Edward IV & Elizabeth Woodville a True Romance, by Amy Licence - Really enjoyed this read and learned a few things about Elizabeth I had to read elsewhere. Also love when an author provides above-and-beyond references.

Elizabeth Woodville, Mother of the Princes in the Tower, by David Baldwin. Much like bell hooks discusses in the Will to Change, Baldwin comes tantalizingly close to naming why we feel the way we do about Elizabeth, but can’t quite pinpoint the patriarchal pressures in the reimaginations. Incredibly entertaining and informative read.

Page 117, Edward IV & Elizabeth Woodville a True Romance, by Amy Licence

Pace 16, Elizabeth Woodville, Mother of the Princes in the Tower, by David Baldwin

Page 118, Edward IV & Elizabeth Woodville a True Romance, by Amy Licence

Elizabeth Woodville, Mother of the Princes in the Tower, by David Baldwin

Page 46, The Woodville Women 100 Years of Plantagenet and Tudor History, Sarah J Hodder

Page 7, A Will to Change, bell hooks - As always, this is a must read.