Lord of the Rings: A Feminist Manifesto for the Boys

A practical guide to overthrowing the patriarchy

Something a little different. A little medieval-adjacent, a little feminist-adjacent, and some much need light for this heady November. Heavy on the LOTR spoilers.

Note: this post is too long for email, please be sure to open in a browser to read in full.

I recently finished the six part story that we know as the Lord of the Rings Trilogy for the first time—at 35. I’ve long loved the movies (extended editions are everything!) and am immensely enjoying the Rings of Power series. I’d picked up the fellowship quite a few times over the last two decades and it always resulted in a DNF. I couldn’t connect, it didn’t feel written for me.

I’m glad the Rings of Power series and its portrayal of leading women made me want to revisit this story, and I’m grateful to have listened to that inkling. Receiving this story in the mental space of 35 allowed me to connect with it in a way younger versions of myself wouldn’t have been able to.

In the below thematic dissection, none of me is saying this is the definitive view, nor even how the story should be received, this is just how I received it. As someone who writes medieval history—a historically male topic—I’m familiar with the reaction to interpretations that aren’t male-centric. Please know my comment section is not the appropriate place for you to dump that into and boundaries will be enforced if you feel it necessary to do so regardless.

To those that intentionally move through our Mother with care, this is for you.

Forcefully forged thousands of years prior.

An all consuming force, to the detriment of all.

A force which dictates behavior, divorcing you from who you want to be, molding you into who it needs you to be.

A looming threat, forcing action, driving decisions.

Men lay slain by the thousands—millions even—to posses its power.

Enforces violent hierarchal structures that benefit few and harm many.

Devastatingly alters the Earth’s climate in support of constant production in service to it.

Socially normalizes brutality, hate, and in-fighting as it was devised to oppress, especially from within.

Requires constant sacrifice.

Disregards the dangers of forced reproduction and diminishes the necessity of care.

Can only be overthrown through community/fraternal efforts.

Is it the one true ring, forged in the fires of Mordor, or is it the Patriarchy?

“He drew a deep breath. ‘Well I’m back,’ he said.” And I closed the book.

The audible sob that escaped my lips felt a Samwise-approved emotion.

As I took in the last line of the series, it dawned on me—with that one line, Samwise was gifting the reader with the knowledge of his wholeness, the beauty of being with yourself and where your soul yearns to be. He was telling us there is wholeness beyond. Beyond the lived reality of harm, beyond these structures. Beyond.

In 1994, Sinead O’Connor released an album titled ‘Universal Mother’. The first track on the album, Germaine, was a voice recording setting the tone for what was to follow.

[Germaine Greer:] I do think that women could make politics irrelevant By as a kind of spontaneous cooperative action The like of which we have never seen Which is so far from people's ideas of state structure And vital social structure that seems to them like total anarchy And what it really is is very subtle forms of interrelation Which do not follow sort of hierarchical pattern which is Fundamentally patriarchal The opposite to patriarchy is not matriarchy but fraternity And I think it's women who are going to have to Break this spiral of power And find the trick of cooperation

The fourth line from the bottom, which is both bold and italicized, is a perfect summation of Tolkien’s six book saga: “The opposite to patriarchy is not matriarchy but fraternity.”

Without fraternity—a word that’s earliest usage is found within documentation of a community of men protecting themselves from patriarchy1—the ring would have fallen into the hands of those that wanted to enforce their will upon everyone else. If the ring took up its rightful place, a place we are reminded often that it yearns to be, love, light, and joy would be utterly lost to Middle Earth.

Therefore, I ask — is the ring of power meant to represent Patriarchy?

bell hooks wrote “patriarchy is a political-social system that insists that males are inherently dominating, superior to everything and everyone deemed weak, especially females, and endowed with the right to dominate and rule over the weak and to maintain that dominance through various forms of psychological terrorism and violence.” The Ring is Patriarchy, and Sauron is the 1% that benefits from it—but note, it harms him too!

The ring’s constant seeking of possession is our first clue of the hierarchical nature of Mordor. But perhaps the clearest reinforcement of this is provided by the nameless entity that identifies as nothing more than the Mouth of Sauron. The text tells us that within seeking favor from his feudal lord, the Mouth’s name and agency were slowly forgotten, his master’s will becoming fully entrenched within his own, seeking to serve it at his own benefit if possible. The Mouth places demands upon the fraternity afore him, insisting on the rebuilding of the fallen Isengard, but there is a catch—it is not for Saruman the disgraced, ‘but one more worthy.’

The fraternity sees through this. “Looking in the Messenger’s eyes they read his thought. He was to be that lieutenant, and gather all that remained of the west under his sway; he would be their tyrant and they his slaves.” Oppression is clearly the flavor of everyday in regards to the social constructs of Mordor and what the ring enforced. It both created dependence and exploited that dependence. As the reader, we’re not told if Sauron has agreed to such machinations, but even the Mouth admits that if it is “surety you crave! Sauron gives none.” Much like men performing masculinity in self-harming ways, the Mouth is performing for another man in hopes of social reward and acquisition to the sensation of power. Under patriarchy and the ring alike, that power results in possession of another’s will within a hierarchical structure.

Gandalf, confronting the Mouth with the knowledge that he is naught but a slave of Sauron himself, is enough to have the lost man running in the opposite direction, whimpering in fear.

Power can not conquer mortality, but both patriarchy and the ring alike expel endless effort to pretend otherwise. The in-fighting of Mordor, that we as the reader are privy to, reinforces that such structures breed contentment and competition, not community. Teetering on the brink of collapse within, projecting violence without.

As I sat there, completed book in hand and Sam’s words reverberating within, I wondered if the Lord of the Rings was a feminist manifesto for the boys: A practical guide to overthrowing the patriarchy.

If you think me satirical, I don’t blame you. I understand how silly it might seem to suggest a story with laughably few women would qualify as a feminist manifesto. But hear me out.

It is evident that Tolkien was a wordsmith, thoughtfully selecting each idiom, building so much with so little. Positioning the biases of learned binary thinking in such a way that easily allowed us (the reader) to accept light=wholesome and dark=dangerous. It wasn’t until I saw this Note out in the wilds of Substack that I realized my initial interpretation of Tolkien’s thematic usage of light and dark wasn’t fully formulated:

So, let me amend:

Light = growth Dark = decay

As an avid composter, fully understanding the beauty that can come of decay, my perspective shifted. All growth upon our glorious Mother is a direct result of decay. Essential nutrients break down in the dark. Life pours forth from the destruction of every seed pod.

The story is clear, each of us are made up of a spectrum of colors, beyond the binary thinking of light/dark, white/black, good/bad. Our outwardly actions and the impact we have upon our community around us determine whether others can perceive our light or not. I propose that not only is light a sign of growth within our story, light is representative of Matriarchy.2 Light is community. Light is care and support. Light is vulnerability, strength, adaptability, wholeness. Dark is decay, but the choice to remain in the dark is Patriarchy. Hierarchical. Dependent upon oppressive structures, trauma, the minimization of the self’s needs and the stripping of community resources that help meet those needs.

As the fraternity stepped ever closer to the oppressive shadow of Mordor, so too did they enter into progressively more patriarchal social structures. The descent into the darkness of Mordor required those raised within matriarchy to confront the dangers patriarchy posed to the very existence of abundant Middle Earth. Those dwelling closest to the borders of Mordor slowly became warped with evil, unrecognizable to the ones that love them—Theoden king but a puppet of Saruman, dwarfed with age in his shadowy, half-lit hall, “but his eyes still burned with a bright light.” While Denethor, steward of Gondor, “is of another sort, proud and subtle, a man of far greater lineage and power”—presented as utterly broken at the loss of his eldest-son. His dark eyes as dark as the hour he finds himself within.

Denethor’s position, steward, finds its roots in Old English. Hierarchical in nature as it is a subordinate role of service, a steward’s position was in the realm of domesticity, the very same realm medieval literature often attributed to the feminine.3 Denethor’s downfall was wrapped up in his inability to understand his rightful position alongside the prioritization of his own plight amidst world-engulfing trauma. For both, he is burned (by our author)—a historically feminine death found within medieval texts. This isn’t to say Denethor was representative of the feminine, but more so what happens to those unable, unwilling, or resistant of properly serving the patriarchy, or in this case, the ring.4

The women

Outside of setting, Tolkien borrows from the medieval often. As we progress through the trilogy, the women that are featured within the story present in Classical ways. The presence of women almost matching the evolution of women’s representation within patriarchal histories and literature alike.

First, we meet Lobelia Sackville-Baggins.

Lobelia is our Eve, she’s covetous and indignant. We never receive a description of her physicality because we are meant to perceive her as unattractive through behavior. She’s bitter that Bagend, the Baggins’ ancestral home, is being passed on to Frodo instead of her (via her husband.) Though we are presented with Lobelia’s longing, we are also clued in that Bilbo’s behavior is in fact a deviation from cultural norms. The possessiveness of patriarchy imposed upon Bilbo through possession of the ring layered with the reader’s internalized misogyny laid fault at Lobelia’s large feet without a second thought.

Next, we meet Mrs. Maggot, the farmer’s wife.

Mrs. Maggot offers care and comfort, she is our medieval every-woman. She “bustled in and out” ensuring the travelers had their needs met. The efforts of her labor hidden in medieval ways: Food is on the table and it is clear that she has been the one to put it there. The support she provides is a necessity but the recognition of labor required to provide such support is not. Even in the face of Frodo’s past wrong-doings (theft of mushrooms), Mrs. Maggot extends grace and support: She sends Frodo off with sustenance in the form of fungi. Food is love to Hobbits, after all, and only in patriarchy is crime met with punishment.

As the fraternity of Hobbits made their way into the wilds beyond the Shire, they met Goldberry, daughter of the River, mistress of the house of Tom Bombadil.

Goldberry is our first medieval babe. Our ethereal and earthly Helen of Troy. She is slender and fair with “long yellow hair” and “pale-blue eyes.” These descriptors are meant to inform us of her inherent power, and though she supports the fraternity with the same feminine-coded labor we saw from Mrs. Maggot, Tom’s partnership in the preparation and cleanup inform us that care is a genderless activity within the space.

Lobelia, Mrs. Maggot, and Goldberry each posses medieval-feminine qualities, however, they also exemplify matriarchal values: They provide systems of support, community care, and encourage the practice of trust—all which become essential for the completion of the fraternity’s mission.

Within the luminous Rivendell we meet Arwen, a fraternity member’s love interest. Here Tolkien borrows much from our Middle Ages. Arwen is the perfect feminine description found within courtly love stories—she is essentially absent from the story yet her tender love is strong enough to propel a man forward into his destiny. Her description too falls within the medieval pattern: “Her white arms and clear face were flawless and smooth and the light of the stars was in her bright eyes.” Light skin and bright eyes are necessary characteristics for a medieval hottie, but also incredibly informing to the power possessed of an individual described as such within the literature.5

After the fraternity resurfaces from Moria, reeling from the devastating fall of Gandalf, we meet the Elven-queen Galadriel. Her home in Lothlorien described in the same light-invoking ways as it’s queen: Both pale and golden. Light and powerful. As Aragorn says to Boromir upon entering her homeland, “there is in her and in this land no evil, unless a man bring it here himself.” Galadriel is presented side-by-side with her husband, the king, yet it is he who does the talking the majority of their visit, playing on the same patriarchal themes of medieval literature. Alongside subtle nods, Galadriel’s power is overtly identified, moving us from the medieval into the Early Modern. Yet the queen and her ladies still provide gendered care—they hand-make essential items for the fraternity, items that go on to save the men time and again throughout the story. Though the making of their gifts includes invisible labor, the continued acknowledgment of what Galadriel has gifted them reminds us, the reader, of her very far-reaching, tenable power.

In their time in Lothlorien, the fraternity is encouraged to rest and tend their emotional and physical scars, both tasks implied as important and necessary prior to moving on—both notably scarce within patriarchy. Though classically patriarchal in outward appearances, the elevation of emotional care and the growth encouraged within the light-filled spaces signifies the matriarchal essence of the community. There is intentional care in Lotlorien, both for one another and the Earth around them. The most ring-swayed among them, Boromir, finds no comfort there.

Tolkien’s deviation from traditionally-masculine descriptors of our featured male Elves and male Hobbits also achieves this gender-bending, matriarchal-signaling. Legolas, our Elven fraternity member, is often described in terms of light: The sun and stars. He is slender, graceful, and golden of hair. His bright eyes sharp and thoughtful. Frodo, our ringbearer, is described as fair and serene, possessing gentle eyes. Samwise, our matriarchal hero, is also lent feminine qualities—he is cheerful, kind, attentive to the needs of the folks around him, rosy and warm with a twinkling in his eyes. Though the story is quite exclusionary of women, it is not exclusionary of the feminine.6 As those qualities are essential, even in the final moments upon Mount Doom.

We the reader are alerted that something is amiss in the land of our next heroine, Eowyn, right away. The gates of Rohan are dark as are the eyes of those guarding it, but the light is shining, sparkling off of gilded armor and golden hair. Joy, love, and light are wanning, but not altogether lost. Eowyn is our mortal Helen of Troy, later warping into a genderless Jehanne d’Arc—she’s moved beyond myth into mortal existence and described in similar fashion: “Very fair was her face, and her long hair was like a river of gold. Slender and tall she was in her white robe girt with silver; but strong she seemed and stern as steel, a daughter of kings.” Though Eowyn is meaningfully medieval, she is also our first woman acknowledged through modernity—challenging the individualism inherent within patriarchy and the proximity of its power.

Tolkien’s quick positioning of Eowyn’s attraction to Aragorn is meant to feed into the biases of gendered behavior—I mean, aren’t we meant to be a little annoyed that she is fawning as the world falls? He’s got things to do, lady! But that is the point! It places Eowyn into the acceptable-to-receive femininity under patriarchy while her behaviors continually challenge that very same status quo. Theodin king insists Merry must be left behind because he is a burden too great for any man to carry, yet our disguised Eowyn willingly bears that burden, bringing our Hobbit to the Battle of Pelennor Fields where his contribution is indisputable.

Eowyn’s agency challenges gender assumptions, but it is also quite clear that it is due to her gender that she is able to prevail while men, kings even, are laid slain around her.

“A sword rang as it was drawn. ‘Do what you will; but I will hinder it, if I may.’

‘Hinder me? Thou fool. No living man may hinder me!’

Then Merry heard of all sounds in that hour the strangest. It seemed that Dernhelm laughed, and the clear voice was like the ring of steel. ‘But no living man am I! You look upon a woman.”7

Eowyn’s steely resolve, “fair but terrible,” slams down into the neck of the winged-beast the enemy is riding, and as our dark foe threateningly rises, Merry brings him back down to his knees with a small blade. Together they are able to fell the foul man, linking in matriarchy rather than ranking in patriarchy. Support, not competition.

But what happened next shocked my movie-consuming brain.

In the Peter Jackson version of these events, it is Eowyn that performs the emotional labor of comforting Theodin in his final moments and he is fully aware of the power she has wielded. However, in the source material, no such thing happens. It is Merry that provides this emotional labor while Eowyn lay unconscious nearby. Tolkien makes it quite clear to the reader that though Eowyn has carried much in the way of invisible burdens, she is unable to complete the task fully without the support and aid of her community around her, highlighting the importance of community efforts over individual acts of valor—aka patriarchal histories.

The destruction of the ring and the fall of the patriarchy

Against all odds, our effeminate and infantilized heroes Frodo and Sam make their way through Shelob’s lair and into the depths of Mordor.8 But before they do so, within the closing chapter of the fourth book housed within The Two Towers, Tolkien reminds the reader of the ever-looming matriarchal presence found within Samwise Gamgee. Sam, weighed down by immense grief, is sure his beloved Frodo is dead, slain by the she-spider in the foul halls of her home. As he kneels over his ring-bearing master, he is overcome with vengeance—if it hadn’t been for Gollum and his continuous treachery, Frodo would still be alive. He ponders, but for a moment, slaying Gollum in a dark corner. Thankfully though, he is recalled to himself. Close proximity to the ring enough for Sam’s internal monologue to uncharacteristically shift for a beat.

“But that is not what he had set out to do. It would not be worth while to leave his master for that. It would not bring him back.”

“But then the answer came at once: ‘And the Council gave him companions, so that the errand should not fail…’”

Even in the darkest, dreariest of moments, the author reminds the reader that a central theme within this epic is the power of community. Frodo was not alone. “The opposite of patriarchy is not matriarchy, but fraternity.”

Sam kisses Frodo’s cold forehead, holds his hands within his own, and openly weeps for his friend. There is no shortage of tenderness between these two throughout their journey. Academia may frame their relationship as homoromantic, but what if we removed the biases placed upon gender and recognized that it was simply two sentient beings seeking community and care within one another in the darkest of times?9 The feminine-coded behaviors and characteristics the Hobbits exhibit throughout the text allow this matriarchal theme to slip under the radar of the more powerful presence of fraternal loyalty.

The ascent upon Mount Doom, the final hurdle, is fraught with patriarchal perils. The burden is too heavy to carry, physically weighing down the bearer. Frodo’s mannerisms fluctuating between dark and light, creating the same Jekyll-and-Hyde tendencies exhibited within Gollum.

Though the ring has warped the creature Gollum beyond recognition, providing a false-sense of immortality, we know he wasn’t always that way. Smeagol10 was once in his life much like a Hobbit—his constant shift between support and vengeance represents the turmoil of patriarchy pushing against internalized matriarchy—made external for the reader. Drawn by the power of the ring, Gollum swears upon it that he will aide the Hobbits in their ultimate quest. Frodo, with full awareness of the destructive constructs the ring employed, foreshadowed the self-sacrifice patriarchy requires of the possessed.

In the final moments, shrouded in steam erupting from the insides of Mount Doom, Frodo is unable to complete his quest. He is fully under the influence of patriarchy—in an instant transitioning into his darkest-self.

Ultimately, the patriarchy self implodes under the wanton possessiveness of it’s everyday bearer. Gollum bites the ring off of Frodo’s finger, jumping with joy, slipping into the abyss lulled under a false sense of power. The ring, and its foot-solider, destroyed together—blind to the danger their very existence had created.

Matriarchy got us to Mount Doom, to the very edge of the treacherous lived-reality that is Patriarchy, but it was patriarchy itself that caused its own downfall. The world had slowly risen up against it, but it was ignorant of the threat due to assumed power and the miscalculation of community. Much like on the fields of Pelinnor, the matriarchy’s power could only do so much under the suppression of patriarchy. It required those predisposed towards patriarchy to fully participate in its downfall.

Tolkien could have easily ended his story with the fall of Mordor, but Matriarchy doesn’t require self sacrifice to uphold it, and the Hobbits needed saving. Gandalf, representative of a reborn non-hierarchal spirituality, ensures they live on to share their story. Spirituality has always played a pivotal role within patriarchal history and it will be necessary if we are to ever overcome it.

Though the lobbing of the ring is positioned as the final climatic event, it is important that Tolkien drives home the narrative of matriarchal community over patriarchal individuality. Gondor’s new king, Aragorn, may have held the imperialist-patriarchal title, but much of his conclusion included matriarchal initiatives. He abolishes enslavement, gives land back to all those that were robbed of it, supports reconstruction efforts, exemplifies forgiveness, and perhaps most importantly, patiently waits for his beloved to give her consent, not once assuming intentions.

The Hobbits, our most matriarchal presence centered around community care and the cultivation of Earth, are confronted with a dreadfully altered homeland upon arrival: The Scouring of the Shire. We’re told that as the remnants of patriarchy fled in fear, they stumbled upon the abundance and grace of The Shire and its inhabitants. Claiming dominion, the outsiders forced imprisonment and servitude upon the Hobbits—role-playing patriarchy in a new space.

Our brave Hobbit-adventurers arrive home and quickly act to secure the safety of their people. With every possible effort, they avoid harming the foul men and instead employ tactics of both war and wit upon them. It is a community effort, every Hobbit involved and duly recognized for their contribution to community within the histories. Each of them heroes in the eye’s of the other. A linked effort. A shared care.

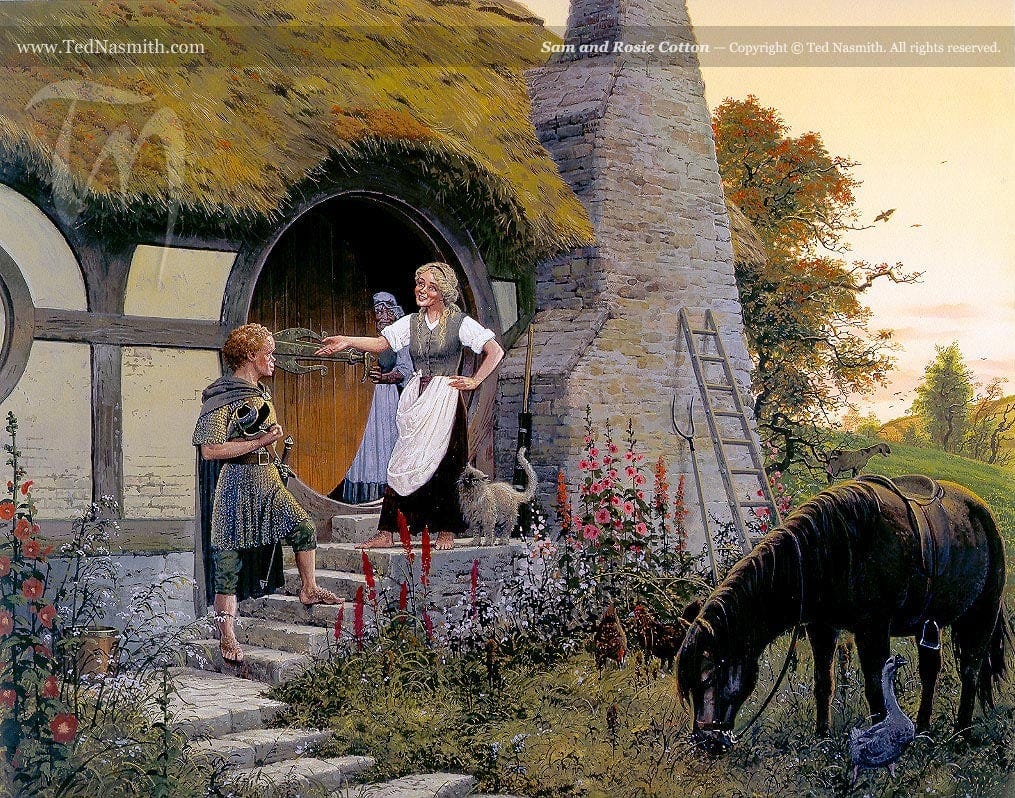

As Sam walked into the cozy confines of his home for the final time, our Mother Mary— Rosey Cotton—plops a baby onto his lap. He may have just saved the world from enforced patriarchal hierarchy, but in their world, childcare wasn’t gendered and he had a job to do.

If the characters that were written with medieval-feminine themes had been presented as women, would Tolkien’s story have been a success? If two women stood within the boiling caverns of Mount Doom, after a perilous adventure across the wilds, would we cheer for them within our patriarchal reality?

So, I guess I ask one last time. Is The Lord of the Rings a practical guide to overthrowing the patriarchy, telling us to link in community rather than rank in hierarchy? I can’t answer that and I’m certain my own biases clouded my reception of the story, but isn’t that the point? Whatever the case, this was a pipe-weed fueled adventure for my brain and I’m grateful you journeyed alongside me. Be well, lovely reader.

https://www.oed.com/dictionary/fraternity_n?tab=meaning_and_use#3650869

In it’s current definition of meaning a society built around community care, could also be read as not-patriarchy. I’ve written posts on the differences here:

https://www.oed.com/dictionary/steward_n?tab=meaning_and_use#20650509

This also isn’t to say that men didn’t die upon the stake, but Denethor’s attempt to manipulate his proximity to power for his own benefit looks similar to the plight of the white woman — upholding patriarchal norms, cozying up to power at their own detriment (and the harm of everyone else.)

Light skin and bright eyes are necessary characteristics for a medieval hottie — according to medieval beauty standards, which of course lingers within modern day beauty standards, no?

This is not to uphold the gender binary, I mean “according to medieval gender expectations”

Dernhelm translates from OE into Hidden Head

Shelob translates from OE into She-Spider

Not to belittle this, but we seek this out often with fellow sentient creatures — I do every single day as I snuggle up with my pup in bed. Only because we’ve placed gender into a binary does it make it necessary to describe relationships between humans with such complicated jargon. All humans need love and care, that is genderless, that is literally just being human.

Gollum’s name prior to losing himself to the patriarchy/ring

All book quotes pulled from: Tolkien, J. R. R. The Lord of the Rings. HarperCollins, 1991.

I love your analysis, and whilst I don't resonante with it all, I admire your bravery in tackling LoTR from a different and refreshing perspective. I first read them over 40 years ago and the books have been a source of comfort and joy and adventure for me. I detest the vitriol aimed at The Rings of Power from a self righteous bunch of mostly male purists and gatekeepers. I say a big joyous hooray and hello to a new, fellow Middle Earth adventurer and her wonderful analysis. Thank you! 🧡

Oh my goodness. I’m a lifelong Tolkien fan & have been in the process of deep-reading his works over the past two years now & this article is by FAR—by FAR—the best/my favorite critical analysis piece I’ve come across. Thank you thank you thank you for writing & sharing this with us! 🫶🏻