‘What is in a name.’

As Shakespeare so aptly wrote, “what is in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell just as sweet.” And he was right, regardless of what you call it, a rose would still smell deliciously sweet, and still be tantalizingly beautiful grasped in the sinewy fingers of your love. The roses value isn’t elevated by how it is referred to. It possess an inherent worth simply by just being. However beautiful a sentiment, Shakespeare himself didn’t bother to give this deferential treatment to the inherent worth of his human subject matter. In 1592, Shakespeare, like the male cultural commentators of today, shared his “imperialist white supremacist patriarchal”1 values through the guise of informational entertainment and false integrity through virtue signaling. Much like Tucker Carlson pushes the patriarchal political agenda of the GOP five nights a week to 3.2 million people via cable and an internet connection, Shakespeare was entertaining the London masses with popularized reimagining’s through the Tudor patriarchal propaganda machine that were his histories. Shakespeare’s prejudices were veiled under the enthralling narrative of the stories he chose to tell.

Then be your eyes the witness of this ill:

See how I am bewitch'd; behold mine arm

Is, like a blasted sapling, wither'd up:

And this is Edward's wife, that monstrous witch,

Consorted with that harlot strumpet Shore,

That by their witchcraft thus have marked me.

-Act III, Scene I, Richard III, William Shakespeare

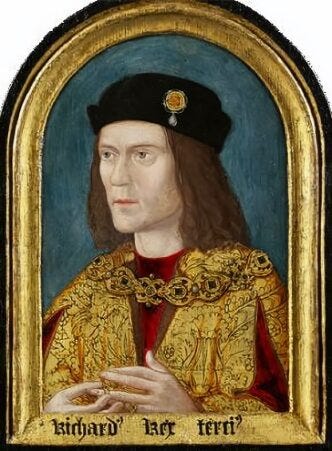

When Shakespeare wrote his history of Richard III, it was over a hundred years after the king’s brutal death on the battlefield at Bosworth. It was also during the dynastic reign of Richard’s decisive victors, the Tudors, whom Shakespeare was deeply benefiting from by pushing their political and dynastic narratives. He was a patriarchal Tudor propogandist much like Tucker is a patriarchal republican propogandist. We shall call him Tudor Carlson.

The ways in which Shakespeare depicted his historical characters still impacts how they are portrayed in the 21st century. Due to historians in large part being unable to recognize where the patriarchy plays into their interpretation of historical events, historical accounts are blurred by the haze that is patriarchal-enforced-and-praised behaviors, especially that of greed. “Historians select what story they are going to tell, then they select what facts they are going to illustrate and prove this story. They make this selection on the basis of what they think is most relevant to their subject, and on what is most interesting to themselves. Just because it’s factual does not mean its innocent of artifice. It is structed: the process of selection, assembly, description, consideration, and ranking facts shows that. There is no such thing as an unbiased, unprejudiced history. The very act of selection of the subject introduced a bias. The authors preferences and opinions are the bias of the history that [they] write, though sometimes readers – reading only one account or perhaps watching only one historian on television – think that this single view represents the totality of the subject. It does not: it cannot. It only ever represents the totality of the view of one historian.”2

Due to the totality of Shakespeare’s influence and popularity, the likes of Richard III went down in history as a hunched-back, shadowy, Machiavellian king, and many assume that to be a true, unbiased fact.

Whatever Richard III might have been, one thing is for certain: he was a champion patriarchal propogandist, skilled at twisting a narrative, and one of his greatest victims outside of his nephews (and all those fellas that lost their heads) was Elizabeth Lambert, or as history now knows her, Jane Shore.

Elizabeth Lambert was born sometime before 1450, potentially around 1445, to her mother Amy and Father John, who was a wealthy London merchant. Because she is a woman not of nobility, much isn’t known about her until after her marriage when she became the favorite mistress of king Edward IV. Though much about Elizabeth is lost to history, we can infer a lot about her character and personality through the documented actions of her life and the words of those that knew her, and through those actions and words, she showed up as an intelligent, quick-witted, composed, seeker of pleasures, seeker of joy, determined, strong, passionate, influential woman who died at the startlingly old age (for the time) of 82. As you can imagine, the patriarchy didn’t like Elizabeth.

Sometime in her teens, Elizabeth married William Shore, a London goldsmith. As a woman in 15th century patriarchal England, much of her upbringing would have been focused on her eventual life as wife and mother, a constant reinforcement that her worth was tied to the roles she held that served men. Her education wouldn’t have looked like that of her noble contemporaries, however, all indication suggests that she was not only literate, but quick-witted and persuasive, or as her lover Edward described, “merry in company, ready and quick of answer." Accounts of Elizabeth after she became Edward’s mistress describe her as influential over the king yet knowing when not to interject on behalf of others. As Thomas More, who knew Elizabeth later in her life, wrote “proper she was and fair … yet delighted not men so much in her beauty, as in her pleasant behaviour. For a proper wit had she, and could both read well and write, merry of company, ready and quick of answer, neither mute nor full of babble, sometimes taunting without displeasure and not without disport … The merriest [of Edward’s mistresses] was this Shore’s wife, in whom the king therefore took special pleasure. For many he had, but her he loved, whose favour to say truth … she never abused to any man’s hurt.”3

Elizabeth officially entered the public record when she petitioned for an annulment to her marriage on the grounds of her husband’s impotence. Again, she would have been brought up with the constant reaffirmation that her worth was tied to her ability to have kids, a focal point of her entire existence up until this point. “Apart from a life of pious virginity, maternity was considered the highest aspiration for a woman, defining herself as a functioning part of, and contributor to, the patriarchal system.”4 And if a woman wasn’t receiving this from her husband, there were grounds for divorce, albeit rare, because it struck one of the basic tenants of medieval womanhood expectations. Elizabeth pursuing this path is a testament to a few of her character traits: a deep knowledge of her own agency, fighting for her desires in the male-dominated society she inhabited, as well as a determined intelligence paired with long-term methodology. She was going after what she wanted, and she was smart and influential enough to do it.

“The recent petition of Elizabeth Lambert alias Schore, of London states that she continued in her marriage to William Schore, layman of the diocese of London, and cohabited with him for the lawful time, but that he is so frigid and impotent that she, desirous of being a mother and having offspring, requested over and over again the official of London to cite the said William before him to answer her concerning the foregoing and the nullity of the said marriage and that, seeing the said official refused to do so she appealed to the Apostolic See.”5

When Elizabeth’s lover, king Edward IV died after suffering a short but painful malady, she was in desperate need for a societal protector, as she had been living comfortably in the favor of the king, and though Elizabeth would have found herself in a scary predicament of being involved with all of the key players of what was about to be an inner-family usurpation, she was quick to secure herself with Edward’s allies. Once again displaying a shrewdness of character and determination of self-assuredness and spirit, continuing to fight for what she believed in, even if that meant jeopardizing her security.

To bring us back into the world that Elizabeth existed within, patriarchal history up until this point had proven that England without a king was a dangerous place, furthermore, England with a child on the throne was a gas-doused primer for civil discordance, disobedience, and skirmishes. The reason for this? Patriarchal greed. As it was, this was the fate of England after Edward’s death, as it left his 12-year-old son to inherit his crown and kingdom. Ultimately, this was the beginning of Elizabeth’s erasure from history, for as a sensual-seeking, intelligent, cunning woman, she posed a threat to the man that was about to be ordained as the next king of England, and it wasn’t either of Edward’s young sons, but was to be his youngest brother, Richard Duke of Gloucester.

Richard, the aforementioned propagandist pro, was third in line to inherit the throne at the time of his brother’s death, but when his two young nephews mysteriously vanished and were presumed dead, this allowed him to cleanly ascend to the English throne without “as much blood to be shed as would be produced by a cut finger.” In preparation for this ascension, Richard needed to ensure that those who would oppose his claim weren’t in any position to be heard from or influential upon the commons, and this he did with startling swiftness.

I do not presume to understand or know the extent to which Richard went to secure his right to the throne, but what we do know is that because of the double-standard of patriarchal propaganda, we’ve been left with a version of history that discredits one family and their allies time-and-again because they dared to defy the patriarchal expected order and behavior of the day: the Queen’s own family, the Woodville’s.

As Elizabeth Lambert was securing her safety in the company of the deceased king’s greatest friend, the Queen’s family was being systematically eradicated and discredited, and unfortunately, Elizabeth was swept into this. It’s hard to differentiate the layers of propaganda from the reality of the time, because not only did Richard ensure every action of his was a power-win for himself and a moral-lose for the Woodville’s, but his version of events allowed for later dramatists such as Thomas Heywood and William Shakespeare to start with ripe source material and run wild from there.

“Then said the protectour; ye shal al se in what wise that sorceres and that other witch of her counsel, Shoris wife, with their affynite, haue by their sorcery and witchcraft wasted my body. And therwith he pluched vp hys doublet sleue to his elbox vpon his left arme, where he shewed a weish withered arme and small, as it was neuer other.”

“Then said the protector; you shall all see in what ways the sorceress and that other witch in her counsel, Shores wife, with their affinity, have by their sorcery and witchcraft wasted my body. And thereafter he bunched up his doublet sleeve to the elbow of his left arm, where he showed us a withered and small arm, which had never been like that before.”

– Kyng Rycharde The Thirde, Thomas More, 1513 (nearly 30 years after Richard’s death)

During the rise of Richard and the fall of the Woodville’s, Elizabeth Lambert was arrested for conspiring with her protector Lord Hastings and the Queen that was in sanctuary, Elizabeth Woodville. Richard had already named Elizabeth Woodville as a witch and had resurrected old, previously dismissed charges against the Queen’s mother, Jacquetta, for her said sorcery. Because Elizabeth Lambert was accused of exchanging messages between Hastings and the Queen, whom would have been Richard’s biggest threats at the time, she needed to be punished for her deviance of patriarchal expectations. Not only was she securing her safety by utilizing her sensuality and body, but she was brave enough to use that very body to support her deceased’s love rightful heir.

Richard’s smear campaign of Elizabeth Lambert was exhaustive. Not only had he consistently named her as a witch and harlot, but he did all he could to secure her public shame and continued discomfort, ensuring the deaths of those she was connected to. Modern patriarchal historians highlight Richard as a pious, chivalric man, being disgusted by the debauchers ways in which his older brother, king Edward IV had behaved. They staunchly defend his decision to the defamation of Elizabeth Lambert, as they partake in it too, without questioning his motivation or inspecting their own. The patriarchy loves to slut shame.

It’s important to note, that regardless if a woman existed as the temptress Eve or the virgin Mary within society, she is still diminished by the patriarchy that enforces the supposed domination of men. We see this in the way women are only being written about historically now that women have access to education at a larger scale. Women’s stories are becoming front and center not because they didn’t exist or didn’t contribute to the shaping of the world, but because patriarchal males wrote the histories to inform and influence other patriarchal males. “Nothing discounts the old antifeminist projection of men as all-powerful more than their basic ignorance of a major facet of the political system that shapes and informs male identity and sense of self from birth until death.”6

The trope of Elizabeth bringing her eventual downfall upon herself for her wanton behavior is quickly proven as a patriarchal fallacy by the way men historically documented, or didn’t, pious and powerful women of the early and late Middle Ages, such as Empress Matilda, who in her own right should have been the first queen of England long before Elizabeth I. Matilda acted with bravery and in accordance to her expected gendered behaviors of the time, yet when she stood within her own power, contemporary writers couldn’t even name her, instead referring to her by her relationships with the men in her life, or downplaying her status. If we inspect women for their wholeness throughout historical markers, we’re able to see their bravery, power, strength, and character; it diminishes the patriarchal narrative of male superiority.

However one may feel about Elizabeth Lambert being a mistress to a married man, it’s important to pause and reflect on the pervasively patriarchal society Elizabeth existed within. She was a young, beautiful woman whose presence deeply impacted a historically persuasive, extravagant, extroverted king. Regardless of her feelings for the king in the end, she wasn’t in a position to be able to safely refuse the offer of becoming a mistress from the start. She did what she needed to secure her survival, livelihood, and comfort, yet historians continue to cast her in the light of sultry mistress, a throwaway character, while in the same sentence uplifting Richard for his piety and chivalric manner.

Richard at this point had beheaded once friends and allies, staged and exaggerated stories of conspiracies, utilized his scoliosis-impacted body as evidence of witchcraft, and had at least two illegitimate children. Whatever Richard was, he wasn’t pious, but the patriarchy forces false integrity upon those that uphold its narratives, and Richard did just that.

Elizabeth Lambert was eventually made to do a public penance, much like we saw with Eleanor Cobham in 1441. Elizabeth was forced to strip down to her petticoat and walk through the streets of London barefoot for everyone to see her open shame and humiliation. However, even amid what would have been a brutally embarrassing moment, Elizabeth Lambert showed us who she was, with Thomas More praising her demeanor even in her darkest hour, stating; “in which she went in countenance & pace demure so womanly, & albeit she were out of all array save her kyrtle only: yet went she so fair & lovely … that her great shame won her much praise.” Elizabeth’s worth wasn’t dictated by Richard’s projection, and she continued to show the world just that, defying the patriarchal propaganda employed against her.

Just fifty-odd years after Elizabeth’s death, a playwright by the name of Thomas Heywood coined Elizabeth as Jane Shore, which Shakespeare later borrowed and built upon. The presumption is that Elizabeth’s name was lost to Jane in order to keep clarity between herself and the queen within the written works. With a flick of the wrist, Elizabeth’s name was lost to history and an entirely new person was created from the imagination of misogynistic men. Yet this is the history of Elizabeth that has stuck.

So, we come back to the question, what is in a name?

Historical patriarchal propaganda will continue to dominate the narrative if we allow it to. Challenging the history you know to be true and reflecting upon which paradigms you may be seeing certain stories through will allow us to continue the efforts of placing women back into the histories that belong to them, as well as securing our future. So, In honor of international women’s day yesterday, I stand in gratitude to all of the women that have come before me and have seen the strength and wholeness in those women whose stories are now only accessible in the archives. My hope is that women like Elizabeth will be provided the respect and dignity to be able to own their respective names.

The will to Change by bell hooks will forever be listed within my footnotes as recommended and influential reading. bell’s work has been vital in my understanding of how patriarchy negatively impacts all of us, especially men.

Phillipa Gregory’s introduction to the Women of the Cousins War has been so influential upon my perception of historical bias within various writings.

Edward IV & Elizabeth Woodville, a True Romance by Amy Licence - I pull from this book a few times for this particular piece, however I haven’t actually read it yet and it would be disingenuous for me to review it. The source material Amy utilizes is incredible and prolific.

See above. I found this quote while sourcing for material and bought the book because of it, admittingly.

See 3.

See 1.