Selling Womanhood: The Medieval Conceptualization, Capitalization, and Concealment of Women's Bodies

In TWO Parts - Part TWO

This is the second part of a two-part essay, please be sure to read part one to fully understand the paradigms within:

Part Two

Concealment in Favor of Continuation

As women’s work became firmly affixed to the domestic sphere, so too did the reductive language identifying the economical labor they contributed. When once a woman would have been given full credit for baking the bread on your table—Old English bæcestre—by the early Modern period, that same woman would have been identified instead as the baker’s-wife. The woman who poured your ale in Anglo-Saxon England? A tæppestre. The woman who poured your beer in Early Modern England? An ale-wife.1 This progressive concealment of women’s labor achieved many nefarious outcomes that still impact us today, but perhaps most insidious of all is the convergence of the laws of the patriarchy-contrived Market with the laws of Human Nature.2

Any historian writing of Medieval women will tell you they’ve read some rendition of the following line a heartbreaking amount of times: not much is known about her.

She has been lost to us.

Evidence of her life is scant.

The consumption of women’s labor into gender identity allowed the labor performed—regardless of how demanding it may have been—to be framed as duty provided rather than labor prescribed. Women such as Yolande of Aragon and Isabelle Duchess of Burgundy, who were integral to the shifting power dynamics of medieval England and France in the 15th century, are known to us because of the privileges afforded to them through both class and gender performance, however, a measly handful of biographies each remind us the implied insignificance of the role women played in the grander scheme of culture-shaping events.

Outside of the privileged few, most women are lost to us because as patriarchy progressed, women were pressed further into gendered servitude deemed unworthy of note by the very same patriarchs recording history. Layers of feminine influence washed from patriarchal annals allow the stories of brutal domination to be positioned as the natural unfolding of human development instead of the intentional outcome of violent hierarchies. We need not look far to witness this very same devastation and framing today.

I don’t believe it too generous to say that without the support of Yolande of Aragon, Charles VII of France would have been unable to resist, and ultimately rout the English to bring about a long-desired end to The Hundred Years War. Of course, as any event in history, it is far more nuanced than that with endless contributing factors, but for a moment let us witness Yolande’s labor.

Afforded unearned privileges at birth, class constructs of the time dictated that the daughter of kings and queens would marry well. In her socially dependent position of Duchess of Anjou, this meant the actions she undertook to further her country’s sovereignty were often framed as duties conducted as expected. In reality? These moments should have been heavily recorded to witness a deviation from the assumed and implied gender norms of the time, but an influence such as Yolande’s would not serve the framework of male supremacy and the biases they wished to enforce.

Yolande’s intelligence and forward thinking can easily be read into the historical space that is allotted to her. Young Charles—like many young men steeped in privilege yet denied divine patriarchal power—exhibited a tendency to react without reflection, often ostracizing vital members of the nobility whose support was necessary to his cause.

Outside of bringing about community around the young Dauphin to support his position, Yolande’s power is tenable in a multitude of ways: From the culturally significant orchestration of the finding of Charlemagne’s sword, to the positioning of importance of the female-view in supporting France’s development.3 Yolande’s life story is steeped with exceptional tales of influence and authority, but would either have been available to her had she not performed her gender thoroughly?

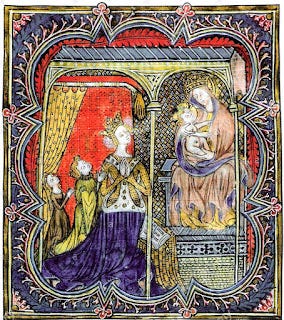

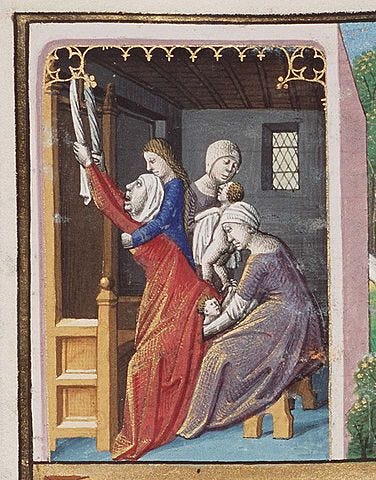

Even within her own wedding portrait (above), Yolande’s beauty is represented in those Antiquarian ways. She need not be anything more than almost a copy/paste of the women around her. Her position of power and paleness of skin are evidence enough of the beauty she possessed, we need not receive individual details of the socially dependent. The diminishment of their individuality and existence in stark opposition to the men across from them. Relying on her immense knowledge of her marital homeland, Yolande was able to properly convince the patriarchs around Charles, and even Charles himself, to receive help in the form of a woman, la pucelle. The maid.4

This young peasant woman, Jehanne d’Arc, would go on to rouse the dampened spirits of Charles’ routinely defeated army in an auspicious way. Up until la pucelle’s entrance onto the scene, The Hundred Years War had been a war of attrition, negatively impacting both kingdoms involved to the umpteenth degree. La pucelle, with her loaned noble armor, ignited the fire under the spiritually driven men, bringing to life a foretold prophecy of France’s ascendancy. Jehanne’s famous deviation from gender performance was initially overlooked as she possessed a separate, often far more important quality under patrilineal patriarchy: she was chaste.

However, once in the hands of the English, this gender non-conformity became a problem of the soul. Unwilling to denounce her interpretations of god’s word nor align herself with prescribed gender expectations, Jehanne was charged as a heretic and burned at the stake. Had Jehanne been willing to wear the damn dress, perhaps she would have been spared. Jehanne has rightly become a symbol for both the queer and trans communities today, whom are at the forefront of breaking down the very same, long-standing, harmful patriarchal gender norms that worked against Jehanne so long ago.

Yolande and Jehanne make it quite clear that women’s work was any work that needed to get done, even in the realm of empire building. The historical concealment of their labor only further served to profit the men around them while firmly cementing the virtuosity in gender performed ideally. One lived out a life of great privilege, while the other was burnt before an audience, not a hand lifting to prevent it. Perhaps the threats weren’t so thinly-veiled after all.

Many an ale-wives names may have been lost to history, but their labor too long concealed need not be. The roots of capitalism stem from the very destruction of women’s agency as witnessed above. As medieval English women warped from distinguished contributors of economy into domestic non-workers, their lack of access to social and financial capital rendered them socially dependent upon the men who benefited from both the open-positions-to-fill and free-labor-provided.

But the patriarchy could not have concealed the women of history without first selling them a concept of womanhood based on implied inferiority.

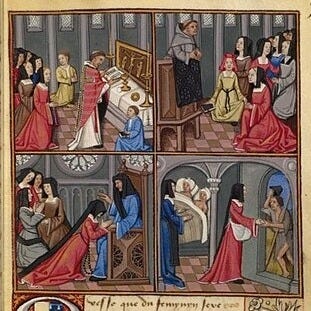

The trades in which women once confidently took up space within (embroidery, brewing ale, midwifery, etc…) were almost exclusively considered the domains of men by the turn of the 16th century. The introduction of hops and the brewing of beer pushed women from the forefront of the production of home-brewed ale to the menial laborers of the beer industry.5 While the exclusion of women from most guilds allowed them to be susceptible to disadvantageous deals and ultimately, exclusion from economy.6

The final force to firmly embed patriarchal superiority within our identity-informing social constructs was issued in 1484 by Pope Innocent VIII in the form of a papal bull titled Summis desiderantes affectibus. The bull decreed, in so many words, that witches were becoming a real problem. So much so that he gave express permission within the bull to interrogate any woman suspected of practicing said witchcraft. Behaviors that warranted such an inquisition? Abortion,7 crop destruction (which patriarchal war often did), intentionally making folks sick,8 and any herbalism related to women’s menstrual needs (among a long list of other things.)

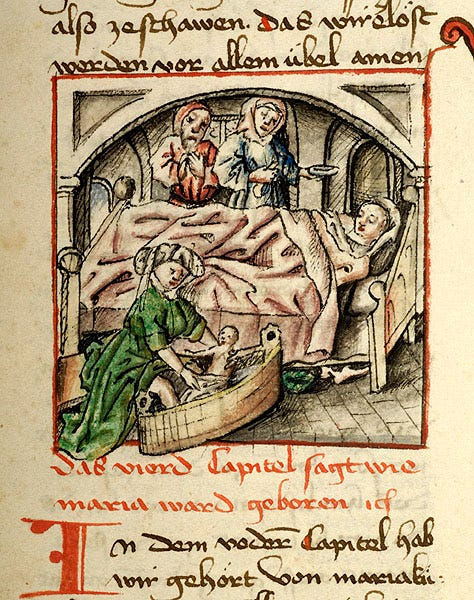

The tendency to insert progressive degrees of separation between ourselves and our medieval ancestors is an anachronism built out of patriarchy.9 It allows us to falsely believe we’ve progressed beyond medieval behaviors, negative connotations et al… Within Women, Food, and the Medieval Diet, Theresa A. Vaughan writes “women are the first food providers we know.” While modern mothers are aided with pumps, lactation specialists (insurance or finances allowing), supplementation of formula, or a choice to opt out all together—as fed is best—medieval women didn’t have such luxuries. Those with patrilineal privilege may have had access to wet nurses, but regardless of which breast fed, without women’s work an undernourished baby didn’t survive. Yet it wasn’t just women’s work to provide nourishment via lactation, as cultural norms (then and now) placed women as the primary provider of any food eaten within a medieval home.10

Alongside the domestic labor of food production, medieval women, and more specifically medieval mothers, were often expected to be the healers of the home—Dr. Mom, so to speak. “A mother would have been taught how to prepare foods suitable for an invalid or a young child, how to care for a feverish child, how to make a congested child breath easier, and when to determine if a child needed more help than the mother could give.”11 The informal side of healing care-giving often requires was expected of medieval women across all classes as an appropriate manifestation of femininity. And as most women were excluded from formal education, this knowledge took on the folklore tradition of being passed down orally, woman-to-woman.12

Those chronicling the world’s events may have overlooked women’s work, suppressing centuries of knowledge from the modern researcher, but contemporary literature could hardly do the same, revealing much of what patriarchal historians deemed inconsequential. Old wives tales became something to distrust, yet the implication is that there were old women/old wives providing community (health)care in the first place. Found within anti-feminist texts such as The Distaff Gospel, written in 1480s France, are coetaneous jabs at women healers and the potential harm that could befall anyone willing to seek them out.13 Though negative, such dissuasive rhetoric stands as yet more evidence that woman-as-healer was a notion medieval readers would have been familiar with.

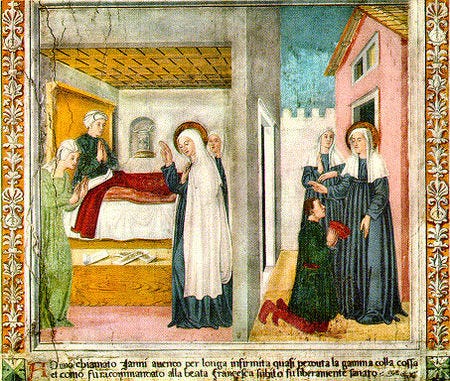

Women’s work included practical healing whereas the medicine of men was theoretical. In the Middle Ages, university-trained “physicians called in to examine a woman couldn’t touch or examine the patient directly.” This required them to rely heavily on the services of informally-trained midwives, particularly in rural areas.14

Within the upper classes of medieval England, not only were male physicians unable to touch their gynecological patients, they weren’t even allowed in the room with them. Confinement was women’s work, caring for the newborn alongside the birthing and postpartum mother was women’s work. Preparing the deceased bodies of any that didn’t make it through the precarious act was also women’s work.15 The intentional exclusion of men meant that these practices were easily manipulated to appear as if they were shrouded in satanic conspiracy. As time progressed into the early modern era, every woman conducting women’s work became culpable.

With an etymology inextricably tied to the feminine,16 the practice of midwifery that was once passed on as women’s generational-knowledge made accessible through the trimmings of the kitchen garden and Commons alike, suddenly found itself as the most prosecutable activity out there. The publication of Heinrich Kramer’s Malleus Maleficarum in 1486, with a later addition published including a Vatican approved preface of the pope’s earlier words, placed the final plank on the complete concealment of women’s labor. The respectability of both men allowed their views on women’s activities to become the definitive views on women’s activities—cozied up nicely alongside the Antiquarians and Papa Geoff alike as the men who determined what exactly womanhood was (is.)

As Silvia Federici rightly asserts within Caliban and the Witch: “None of the tactics deployed against European women and colonial subjects would have succeeded, had they not been sustained by a campaign of terror. In the case of European women it was the witch-hunt that played the main role in the construction of their new social function, and the degradation of their social identity.”17 The mask of respectability politics may no longer allow women to be stoned in the street for asserting control over their own bodies, but the insidious tradition of utilizing governmental agencies to force control over marginalized groups is still in full-effect.

A suit filed by multiple conservative states on October 11th, 2024, reinforces this very notion. The opening line, reminiscent of the framing found within la Tour Landry’s text, asserts the case as a chivalric act to protect women: “Women face severe, even life-threatening, harm because the federal government has disregarded their health and safety.”18 Ah, the federal government, the pinnacle patriarchal protector. La Tour Landry’s stance was only slightly different. He was going to teach his daughter’s to be women beyond reproach, to negate even the need for such litigation.

To properly preform femininity, according to la Tour Landry, was to preoccupy oneself at the constant benefit and behest of their lord-husband (if married), lord-father (if single), or man (if woman). Specifically in that order.

“For there be sucℏ men that lyethe and makithe good visage and countenaunce to women afore hem, that scornithe and mockithe hem in her absence.”

“A woman aught not to striue with her husbonde, nor yeue hym no displesaunce” Doubling down on this particular point placing the onus of domestic violence squarely on the shoulders of women.19

“And therfor the wiff aught to suffre and lete the husbonde haue the wordes, and to be maister, for that is her worshipp”

Both the prosecution and the patriarch are positioning that they, as patriarchal institutions, seek only to save women from the very same patriarchal institutions that they represent and profit from.

The framing of this suit is meant to startle women into believing the prosecution seeks to protect them. Buried under 190 pages of good-time legal jargon is the very same reductive language found within medieval ordinances. The teens shouldn’t be allowed online access to abortifacients, even with permission from a parent. Even under guidance of a medical practitioner. Because they are needed to populate our states or else there may be a “loss of federal funds” at the state level (below).

The patriarchy’s respectability politics removed from the collective conscience women’s everyday knowledge of abortifacients and birth controls found within the community’s gardens.20 Women’s work alongside women’s knowledge has been concealed from us to further perpetuate the normalcy of rendering your rights upon the social construct of marriage, providing endless “evidence” to the traditional nature of such an imposition. And though we’ve progressed far beyond reaching to our gardens to assert our own agency, we haven’t progressed beyond respectable men attempting to minimize the expansiveness of womanhood into the blessings of confined domesticated servitude.

Just because we are into the fourth year of our own plague-years doesn’t mean we should allow medieval practices—which seek to define womanhood solely through terms of reproduction—to manifest within modern governance. Women’s personhood should be nonnegotiable. Please be sure to vote like it.

Nuttall, Jenni. Mother Tongue: The Surprising History of Women's Words. 2024

Though this is not a quote, I would not have had this thought without:

Courville, Cindy. “Re-Examining Patriarchy as a Mode of Production : The Case of Zimbabwe.” Theorizing Black Feminisms: The Visionary Pragmatism of Black Women., 1993.

Barker, Juliet R. V. Conquest: The English Kingdom of France, 1417-1450. 1st North American ed. Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press, 2012.

Ibid.

Federici, Silvia. Caliban and the Witch. Autonomedia, 2004.

Goldberg, P.J.P. Women, Work, and Life Cycle in a Medieval Economy: Women in York and Yorkshire c.1300-1520 (Oxford, 1992)

Which would have been difficult to discern from miscarriage

Again, something patriarchal war often did, just ask Henry V

MAGA romanticizes patriarchal history in the same way

Vaughan, Theresa A. Women, Food, and Diet in the Middle Ages. Balancing the Humours. Amsterdam University Press, 2020.

This isn’t to say men didn’t nor don’t contribute to domestic labor, but women in western cultures have historically done this work. Colonialism further perpetuated these gendered stereotypes worldwide.

Vaughan, Theresa A. Women, Food, and Diet in the Middle Ages. Balancing the Humours. Amsterdam University Press, 2020.

Federici, Silvia. Caliban and the Witch. Autonomedia, 2004.

Vaughan, Theresa A. Women, Food, and Diet in the Middle Ages. Balancing the Humours. Amsterdam University Press, 2020.

History of Women in the West, Volume II: Silences of the Middle Ages. Ed. Christiane Klapisch-Zuber. Harvard University Press, 1992.

Federici, Silvia. Caliban and the Witch. Autonomedia, 2004.

“Midwife, N., Etymology.” Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford UP, September 2024, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/5618839815.

Federici, Silvia. Caliban and the Witch. Autonomedia, 2004.

https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.txnd.370067/gov.uscourts.txnd.370067.195.1.pdf

For the above and below quotes

The Book of the Knight of La Tour-Landry, EETS o.s. 33, London, ed. Thomas Wright (from MS Harley 1764 and Caxton's Print) rev ed. 1903

Federici, Silvia. Caliban and the Witch. Autonomedia, 2004.

Your dedication to including medieval knowledge and even text to inform the common woman of how her rights have been systematically stripped away through the ages is both enlightening and necessary for growth to occur in us. Thank you for the immense amount of time you put into writing this well-penned essay!

There is some really interesting scholarship out there about how the new royal medical academies in the 17th century mined women’s receipt books for knowledge that then was absorbed into the male-controlled fields of “medicine” and “science.” Contemporaries and historians (especially the historians) then ignored women’s role and credited the male Academy members. I’d love to hear your thoughts on this one day.