When I sat down to write Everyday Women as Agents of Change I hadn’t intended to focus entirely on the English peoples’ revolt of 1381. However, the further I got into writing—and the further I deviated from my writing plan—the more I wanted to investigate the deep inequities legally enforced. The more I wanted to disrupt the hegemony of masculinity surrounding the stories of revolution. I couldn’t ask Margery Starre, Matilda Aleyn, Katherin Gamen, or Alice Wymond to be yet another footnote—a supporting role—in a larger story. These women weren’t the disembodied medieval maidens propelling the story forward through a distant, promising, promotional love. They were the story. As connected to and impacted by the outcomes as the men around them. Just as deserving to feature at the forefront of the narrative as those that have for centuries.

I didn’t share their stories to uphold or glorify their violence. I shared their stories to combat the storytelling of the dominant culture: to counter patriarchal propaganda and the masculinization of collective power. History, as it stands, often serves only to reaffirm patriarchy (male supremacy achieved through institutionally supported domination), oft utilized to deter those intentionally seeking a more cooperative and egalitarian future. Propaganda designed and deployed for this exact reason. We can’t escape our history, after all.

As an abolitionist feminist I believe in nonviolence and the preservation and inherent value of life, thus I was torn. How do I tell the story of revolutionary women without falling into gendering behavior or promotion of said behavior? Violence is not the prerogative of masculinity, but humanity, after all. Instead, I chose to honor that these women—through the reality of their violence—sought to defy the very dominant culture that had espoused and promoted such violence in the first place. The revolt may not have occurred for, or under, a cooperative action, but it was a collective effort to disrupt the very institutions responsible for depriving both resources and labor from the everyperson. The very institutions which, in their establishment, directly disadvantaged women the most! It wasn’t actions of a collective feminism, nor even a proto-feminism driving them forward, but it was a direct appeal against dominating and oppressive hierarchies. Ruminations of feminism, if you will.

Medieval women were harbingers of change in ways well beyond the violent actions witnessed in 1381. Far from being the aggressors inflicting patriarchal violence, they were often protectors from it—safeguarding community through collective action—which was too often undocumented and therefore deemed unimportant under patriarchy. Below are the women from the original writing plan that didn’t quite fit into what turned out to be the story of England’s revolt of 1381, but they too challenged the modern notion of novelty around medieval women’s collective action for community enrichment. They too challenged the imposed construct of the medieval world which fervently insists women only occupied and influenced private spaces.

The Captain’s Wife (English held Avranches, Normandy 1450)

John Lampet’s wife—whose name is lost to us due to the objectification imposed upon her within the institution and representation of medieval marriage—knew the fall of her community was inevitable.1

Just four days prior less than one hundred kilometers to the northeast English-held Bayeux had violently fallen back into French hands. Her English compatriots had been made to march out of town in utter destitution after a relentless siege; A stick in hand signifying their complete lack of chattels and weapons, nary a resource in sight to support this newly exiled community. This simplistic sign of safe conduct in stark contrast to the bloodshed—the destruction of both English and French souls—that had occurred just days prior.

For sixteen long, hard days Bayeux had been battered by the merciless French guns determined to reposes their homeland, resigned to rebuilding if need be all in the name of ejecting the English foes. Walls disintegrating to dust under the relentless besiegement; Death’s bell camouflaged by the constant bombardment the community was forced to endure. A community not just of English that had been made to move by order of one lord or another, but French citizens who had chosen to surrender instead of forgo all sense of livelihood—namely, French women that had married the deployed English men-at-arms.2

Back in Avranches, our captain was unable to fulfill his position as chief protector of the town’s defenses, and having been forewarned via a faithful and quick moving messenger, his wife knew all to well what awaited them. Instead of being overcome by fear, our captain’s wife was resolved to protect her community from the incoming peril. Donning men’s clothing she went house to house, fists wrapping urgently upon her neighbor’s doors imploring the inhabitants to join in beating back the besiegers. So encouraging was she that this defensive effort would wear-down and stave off the French attackers for three long weeks. Weeks of life bought for her community with hopes of escape. However, once it was obvious defeat was inevitable, she reverted to “feminine dress to enchant Francois of Brittany into granting the best terms.”3 Because of the quick and daring actions of our captain’s wife the English were allowed to depart with their lives, though not much else.

“Honest women who are called beguines” (Paris, France—with mentions of greater Europe—1254)

In everything a Beguine says

Listen only to good

Whatever happens in her life

It is religious.

Her word is prophecy;

If she laughs, it is amiability;

If she weeps, it is devotion;

If she sleeps, she is ravished;

If she lies think nothing of it.

If the Beguine marries

That is her conversion:

Since her vows, her profession

Are not for life.

Now she weeps and then she prays

And then she will take a husband:

Now she is Martha, now she is Mary

Now she is chaste, now she marries

But do not speak ill of her

The king will not tolerate it.

-Rutebeuf, ‘Li diz des beguines’Medieval Europe is often depicted as a particularly masculine affair. Our tales of chivalry supported by nearly invisible maidens motivating heroes onward. The knight’s role to safeguard maidens, widows, and orphans, patriarchy’s most pathetic dependents—namely for their unattached and available to become another’s dependent status—still influencing modern masculinity under the guise of propping up provide and protect as idealistic expressions of manhood. As imperialistic patriarchy siphoned the labor and resources from the many into the purses of the few, it was women that stepped up to care (read: provide and protect) for their communities let down and disregarded by those divinely in charge.

Across Europe thousands of women rejected the patriarchal expectations of their gender and adopted the charitable and spiritual lifestyle of the beguine. “Never canonically recognized as religious in the strict sense of the word, beguines did not follow an approved rule, did not live in convents, and did not give up their personal property.”4 These women remained in control of their time, laboriously utilizing it for collective care.5 They were able to marry and abandon their vocation at will all while having access to an environment where fierce connections with other women weren’t just possible, but deeply encouraged.6 As Tanya Stabler Miller noted in The Beguines of Medieval Paris: Gender, Patronage, and Spiritual Authority it was the flexibility and dynamism which drew these women in to the the beguine vocation—becoming one of the beguinae offered a rare form of agency to women of certain socioeconomic backgrounds heretofore unavailable to them.

By the 1250s, the beguinae were so common a sight in Paris that Louis IX issued protections around their treatment and purchased lands in the parish of Saint-Paul to establish a foundation to house them.7 A home base of sorts for the everywoman that devoted herself to the wellbeing of her soul and community—the very community Louis was charged to care for. Prior to the establishment of these institutionally supported beguinages women of these communities often purchased neighboring homes, creating their own support network in order to most efficiently achieve their intentionally selected vocation.8

In Cities of Ladies: Beguine Communities in the Medieval Low Countries, 1200-1565, Walter Simons noted:

“Despite claims of various early modern and modern mythologies, the beguine movement was not the creation of a single individual, male or female. Indeed, the earliest manifestations of the movement are unusual and fascinating precisely because communities of like-minded women seeking a novel way of life, pursuing similar goals and connected by various individuals who moved between them, sprang up in different places in the southern Low Countries within a relatively short time.”

And much like the French beguinages, these communities included women who were caretakers and nurses for the collective well-being both within the walls of the beguinage and without; Women who pursued contemplative callings of their own desires; Women who challenged the shortcoming of the patriarchal church;9 Women supporting one another in a non-hierarchical environment through practicing informed inheritance decisions;10 Women employing publicly acknowledged agency and authority from across a wide swath of socioeconomic backgrounds; Women defying a long imposed public/private construct of the medieval world. Indeed, the walls of the beguinage were seemingly brimming with stories of women that challenged the very notion of patriarchy itself: Women thriving outside of the purview of male authority.

Through relentless effort to provide for those forgotten and discarded within the hierarchical hardships invoked by a patriarchal structure, the beguines set out to establish themselves as sources of support, learning, piety, and trade across Europe by promoting interconnectedness across the movement. They saw a public in need and took it upon themselves to rigorously care for it, unwilling to wait for the institution that caused such ills to right its wrongs. Aside from meeting the bodily needs of a community, beguinages were a magnet—a social hub of sorts—to those across the medieval French socioeconomic landscape for their intellectual, economic, and artistic pursuits.

“By the fourteenth century, the beguinage had a school where young girls from their city, and perhaps beguine residents, were taught the fundamentals of reading and writing.”11 These were sites where spirituality and education could be pursued if only one had a desire to do so, where women not only possessed autonomy and agency, but recognized and actualized authority that extended far beyond the walls that housed them. Because of this intentional countering to patriarchal culture, and because these were spaces where female bonds were fiercely forged to counter the hardships instigated by the dominant culture, we can hear a quiet note of proto-feminism reverberating to us from the past.

But it was more than just the friendships of other beguines that enriched the lives of the women who willfully joined the movement. “The rules of the community allowed individual ownership of movable and immovable properties, thereby enabling beguines to use their wealth to support themselves and their fellow beguines and to contribute to the local economy, whether by investing in annuities, establishing workshops, or loaning money.”12 These were entire communities of women operating outside of culturally enforced gendered constraints, often in ways that afforded them real power in patriarchal social structures.13 Actions which would receive praise alongside condemnation from contemporaries keen on policing and benefiting from gender expression as expected by patriarchy—a tenor which rings true to modern day readers.

French trouvère, Rutebeuf, whose words opened this section, was one such detractor. Satirical in nature, Rutebeuf’s ‘Li diz des beguines’ criticizes the practicing women for their emotive ways. He condemns them for their access to be both Martha, a wife concerned with earthly tasks, and Mary, the virgin concerned with spiritual ones. He mocks the unseriousness of women that show up in such ways, disbelieving their devotion without the assurances of a lifetime vow of chastity. The patriarchal anxieties of women living outside of male authority are wrapped in his words and palpable to readers some seven hundred years later. To men like Rutebeuf and his contemporary, the priest William of Saint-Amour, the beguines we’re just “silly” girls engaging in “silly” heretical acts in need of a man’s guiding hand.14

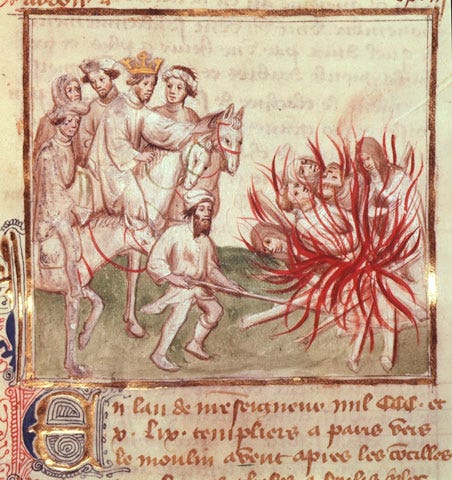

Public and Private Spheres (Place de Grève, Paris, France, 1310)

On May 31st, 1310, Dominican inquisitor William of Paris turned away from the woman he had just condemned to death and carried out the remainder of his charged duties. Taking a deep breath, channeling all of the patriarchal authority afforded him, he settled his gaze upon his next victim, another destined for the flames intended to burn out heretical thinking by its roots.

His next victim, a book, had been written by the woman he had just sentenced to burn. Unwilling to acknowledge the book’s name, William chastened:

"And the said book we condemn by sentence as heretical and erroneous, as containing errors and heresies by judgment and counsel of the masters of theology residing in Paris, and now we want it to be exterminated and burned, and strictly order that every and each person having the said book, under pain of excommunication, is required to turn it over without fraud to us…”15

Intoning condescension aside, William’s words alert us that there were likely other copies of the book—perhaps many other copies—and it was his stated intention to cull them from the collective. Yet, if we were to hold true to the imposed paradigm of a medieval world dictated by gendered public and private spheres, our condemned author Marguerite Porete and her potential widespread readership should have been an anomaly. In truth, she was one of many.16

The didactic Marguerite “deliberately and energetically circulated copies of her book, showing it to clerics, monks, and theologians and reading it to lay audiences.”17 By writing her book in the vernacular, Marguerite ensured its message could be received by the most people possible when read aloud—an action which directly defied, while being wholly aware of, the exclusivity imposed by patriarchal circles loyal to utilizing Latin. It is in William’s own words we find confirmation that Marguerite had been a transient woman potentially possessing a large network of readers, as the “well-remembered” Guy Bishop of Cambrai had “publicly and unmistakably” burned her book in her presence some 200 kilometers northeast of where she was executed.18

Though Marguerite had gone to great lengths to compose her own story, it would ultimately be one brought to us by men in positions of patriarchal privilege. Men such as William of Paris and Guy of Cambrai who had separately condemned Marguerite for spreading the belief that one should act in complete accordance with god’s will, negating the need to seek absolution.19 Men such as those surrounding John bishop of Chalons who would swear that Marguerite had sent him a copy of her book after she was first convicted of heresy. Men like William of Nangis who, as eye witness to Marguerite’s execution, marveled at her “noble and pious” countenance all while condescending the “little book” that catalyzed such events to unfold in the first place.20

Regardless of which masculine framing we receive Marguerite’s story through, however, what we witness from afar is her audacious and steadfast spirit intent on harbingering a more peaceful and loving future through the messaging of her own words. A complete countering to patriarchy’s long held notion of an unchallenged segregation of the sexes with one gender possessing authority over all others—which is exactly why Marguerite was forced to endure the flames. Onlookers need not be literate to interpret the undertones of such messaging.

After her inhumane death chronicler William of Nangis referred to Marguerite as a “pseudo-woman.”21 A clear example of patriarchy’s attempt to dictate gender norms; A near constant effort to limit the expressions of womanhood in ways which directly benefit patriarchy. Marguerite’s refusal to heed the words of men and her persistent patriarchal countering disqualified her from the column of acceptable displays of womanhood.

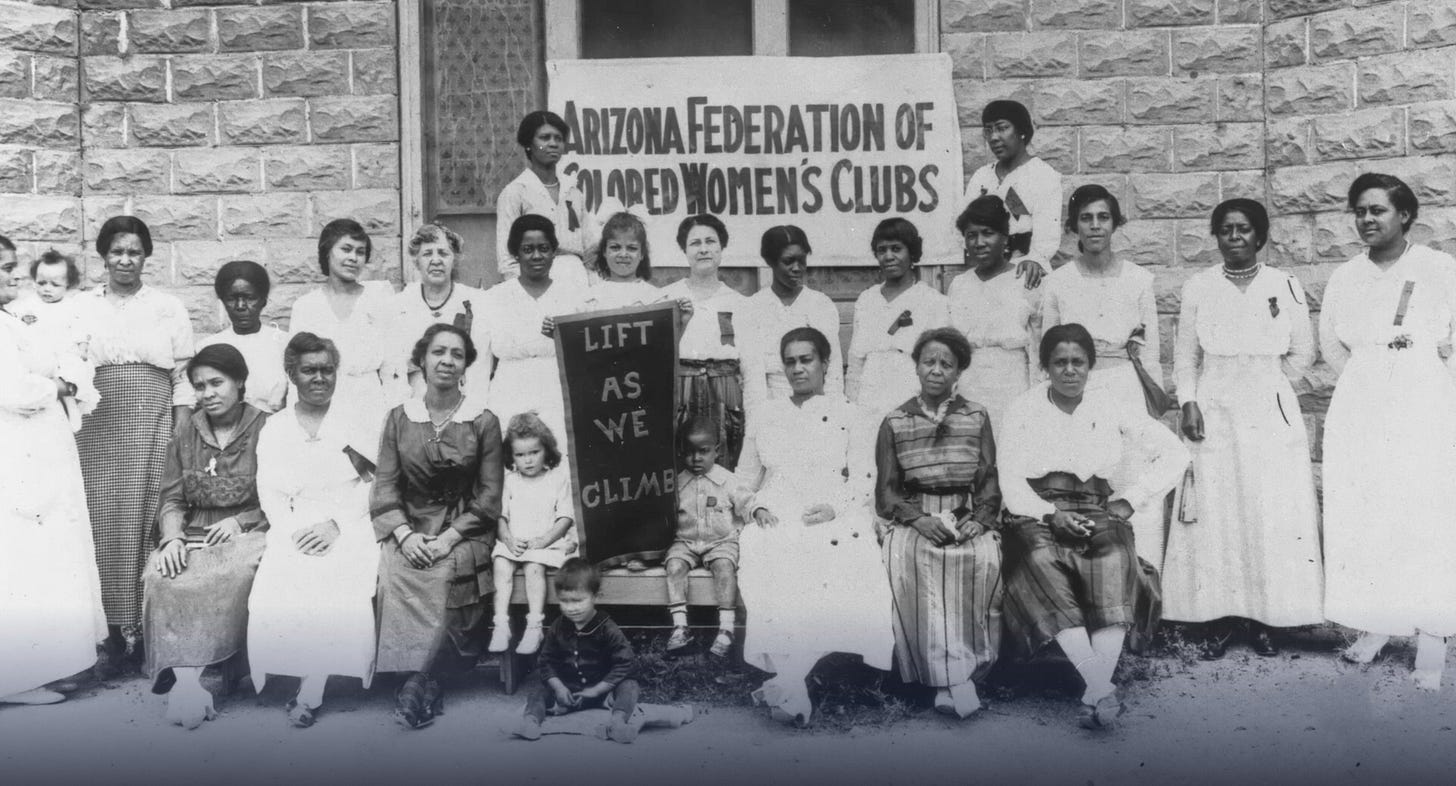

As we witness modern patriarchs attempt to litigate women back into complete dependency, know that this isn’t a new trick, but the very same one that brought us into modernity from the medieval: This is imperialist white supremacist capitalistic patriarchy. To counter it we not only need to use our voices, but uplift and preserve the voices of the most marginalized among us. As the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs captured in their 1896 motto—one hundred and twenty nine years ago—“Lifting as We Climb” is the only way forward.22

Writer’s note: Marguerite’s book The Mirror of the Simple Souls Who Are Annihilated and Remain Only in Will and Desire of Love—or The Mirror of Simple Souls—is available to be read both in-print and digitally. Her words long outlasting the man who burnt them.

Blondel, Robert. ‘De Reductione Normanniae’ in Rev. Joseph Stevenson (ed.), Narratives of the Expulsion of the English from Normandy. London, 1836

Barker, Juliet. Conquest: The English Kingdom of France, 1417-1450. Harvard University Press, 2012.

Ibid.

Miller, Tanya Stabler. The Beguines of Medieval Paris: Gender, Patronage, and Spiritual Authority. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014.

Neel, Carol. “The Origins of the Beguines.” Signs, vol. 14, no. 2, 1989, pp. 321–41. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3174553.

Miller, Tanya Stabler. The Beguines of Medieval Paris: Gender, Patronage, and Spiritual Authority. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014.

Ibid.

Simons, Walter. Cities of Ladies: Beguine Communities in the Medieval Low Countries, 1200-1565. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001.

Neel, Carol. “The Origins of the Beguines.” Signs, vol. 14, no. 2, 1989, pp. 321–41. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3174553.

Simons, Walter. Cities of Ladies: Beguine Communities in the Medieval Low Countries, 1200-1565. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001.

Miller, Tanya Stabler. The Beguines of Medieval Paris: Gender, Patronage, and Spiritual Authority. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014.

Ibid.

Much has been argued in way of proving the beguines used alms and begging as a means of accomplishing their goals, though more recent research indicates the idea of a beggar beguine is far from reality and only used as propaganda against them, then and now.

Miller, Tanya Stabler. The Beguines of Medieval Paris: Gender, Patronage, and Spiritual Authority. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014.

Field, Sean L. The Beguine, the Angel, and the Inquisitor: The Trials of Marguerite Porete and Guiard of Cressonessart. University of Notre Dame Press, 2012.

See Hadewijch of Brabant and Mechthild of Magdeburg. Christine de Pizan would also intentionally counter in the vernacular vs. Latin during the popular debate de la Rose

Miller, Tanya Stabler. The Beguines of Medieval Paris: Gender, Patronage, and Spiritual Authority. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014.

https://uncg.edu/~rebarton/margporete#:~:text=Marguerite%20was%20one%20of%20the,stake%20in%20Paris%20in%201310.

Field, Sean L. The Beguine, the Angel, and the Inquisitor: The Trials of Marguerite Porete and Guiard of Cressonessart

https://uncg.edu/~rebarton/margporete#:~:text=Marguerite%20was%20one%20of%20the,stake%20in%20Paris%20in%201310.

Ibid.

https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/eras/civil-war-reconstruction/national-association-colored-womens-clubs-inc-1896/#:~:text=The%20merger%20enabled%20the%20NACWC,and%20regional%20Black%20women's%20organizations.&text=The%20NACWC%20adopted%20the%20motto,promoting%20self%2Dhelp%20among%20women.

top image source: https://lsintspl3.wgbh.org/en-us/lesson/ull20-suffrage/5

Yes, yes, and yes again. This is a terrific and much needed historical course correction, meaning both a ship and a curriculum. I, too, feel keenly about writing about women and violence. But many theologians and philosophers agree that there are certain conditions where violence is justified—when the intention is to prevent harm. Self-defense, for example, is the lesser evil. But, you make a strong point that violence should not be celebrated but also not erased from our past. History is the story of all of us, flaws and all. We can, and we must, aim to make harmful violence a thing of the past.

I loved reading this variety, and in these days I'm especially intrigued by the subversive writing and sharing of books by Marguerite Porete.