The Preservation of Women’s Words

This boke is myne, Eleanor Worcester An I yt lose, and yow yt fynd I pray yow hartely to be so kynd That you wel take a letil payne To se my boke is brothe home agayne

Inscription in a Book of Hours belonging to the Duchess of Worcester, c. 1440

My daughter’s school runs the parent-pick up line as efficiently as a Chickfila drive-through. Filing caregivers orderly ahead, smiles and positive attitudes pasted on the faces of the educators while they hustle you onwards. As I patiently waited for my respective turn to scoop up my child, I could visually see my girl struggling with her bag from afar. When it was our turn to scoop-and-scoot, I side-arm grabbed the bag across the passenger seat and investigated while idling forward. “Why did Mrs. W send all of these books home?”, I queried—not ungratefully. “She knows I love to read!” replied my sweet then-six-year-old. I took it at face value because that is exactly the type of teacher Mrs. W was. The kind of teacher we all hope our child gets, the one that radiates excitement about teaching and genuinely cares about the well-being of your child. Mrs. Frizzle with a southern drawl.

Fast forward to the end-of-year community garage sale, where Mrs. W was selling a library’s worth of books for literal nickels and dimes. At the end of the sale, as my family and I cleaned up our vegetable-starter booth, Mrs. W walked over with yet more bags full of books and asked if we’d like to bring them home. She confessed that she had to empty her classroom of twenty years due to the rampant book bans; it was easier to start fresh rather to inspect the hundreds of books that had accumulated over a long, joyful, and sparkling career as a kindergarten teacher. For one third of Florida’s book bans originate from my child’s school district, 94% from one single man. A white man. A white conservative man.

Florida—a state touting a curriculum for middle schoolers which declares “slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit”1—is actively scrubbing it’s bookshelves, both in public schools and public libraries, attempting to silence already marginalized voices.2 Voices such as Toni Morrison’s Beloved and

’s Not That Bad declared unfit for public consumption by a man without educational experience, without lived experience of being either Black or a woman in this white-male-centric world. One of these books tells of the soul-shattering realities of enslavement, including the devastating decision to choose infanticide over a life of forced enslavement for a child, while the other centers women’s voices and shared experiences of the trauma inflicted upon us whilst living in a white-supremacist capitalistic patriarchal society. The erasure of these works and the voices of other marginalized folks, masked in a morality crusade, promotes adherence to a single-story3, a single reality, one which allows cis-het white-men to not only comfortably exist, but to feel superior within.The adherence of a single story is all around us: In the headlines reporting that 30,000 Palestinians have died, as if happenstanced into an early demise, while refusing to name the government entities complicit in a genocide of a people. It is what allows for silence to follow the destruction of Gaza’s archives, universities, museums, mosques, and other culturally significant sites in the same world that crowd-sourced funds for a burning Notre Dame. It is in the stories told of discovery rather than the reality of destruction which followed the Western expansion. It is the deep rooted xenophobia of our ancestors which instilled in us that indigenous people were barbarians simply because they did not live according to Western patriarchal standards. The patriarchy has long employed the influence of the single story, made evident in the tales of Great Men alongside the almost-complete exclusion of women's voices from the historical records. For the erasure of women is man-made, all in service to the patriarchy.

When Winston Churchill said “history will be kind to me, for I intend to write it”, he wasn’t speaking hyperbolically, he was putting on full display not only the awareness of the power of patriarchal propaganda, but who gets to wield that power. “Power is the ability not just to tell the story of another person, but to make it the definitive story of that person. The Palestinian poet Mourid Barghouti writes that if you want to dispossess a people, the simplest way to do it is to tell their story and to start with, "secondly." Start the story with the arrows of the Native Americans, and not with the arrival of the British, and you have an entirely different story. Start the story with the failure of the African state, and not with the colonial creation of the African state, and you have an entirely different story.”4

Women have long seen through—and combated—this particular puzzle-piece of oppression. In 1991 Mari Matsuda reminded us the importance of “[asking] the other question to better understand the interconnectedness of all forms of subordination. Matsuda said “when I see something that looks racist, I ask, “where is the patriarchy in this?” When I see something that looks sexist, I ask, “what is the heterosexism in this?” When I see something that looks homophobic, I ask, “where are the class interests in this?” Working in coalition forces us to look for both the obvious and the nonobvious relationships of domination.”5 And through the trenches of forced marginalization and overlapping forms of subjugation, women have long ensured, covertly, the continuation of women’s words and recognition of impact by defying the story of ‘secondly’ and asking the other question.

Female Rivalry, a Patriarchal Phallusy

In her pioneering essay Medieval Women Book Owners: Arbiters of Lay Piety and Ambassadors of Culture, Susan Groag Bell aptly argued “the power of the word is the greatest and most far-reaching power known to society. In slave societies it was too dangerous to teach slaves to read, as their literacy would surely lead to rebellion.”6 The patriarchy has long relied upon limiting access to education, book bans, and book burnings to silence contrary beliefs and limit human reality. Access to knowledge is access to power, and the patriarchy has too often demonstrated its unwillingness to share that power. Women’s access to equality—rather, what the patriarchy has dubbed equality whilst still actively denying our personhood and never treating us as equals—is often framed as something that has been given to us rather than something that has been taken from us: we were given access to education, yet knowledge is genderless.

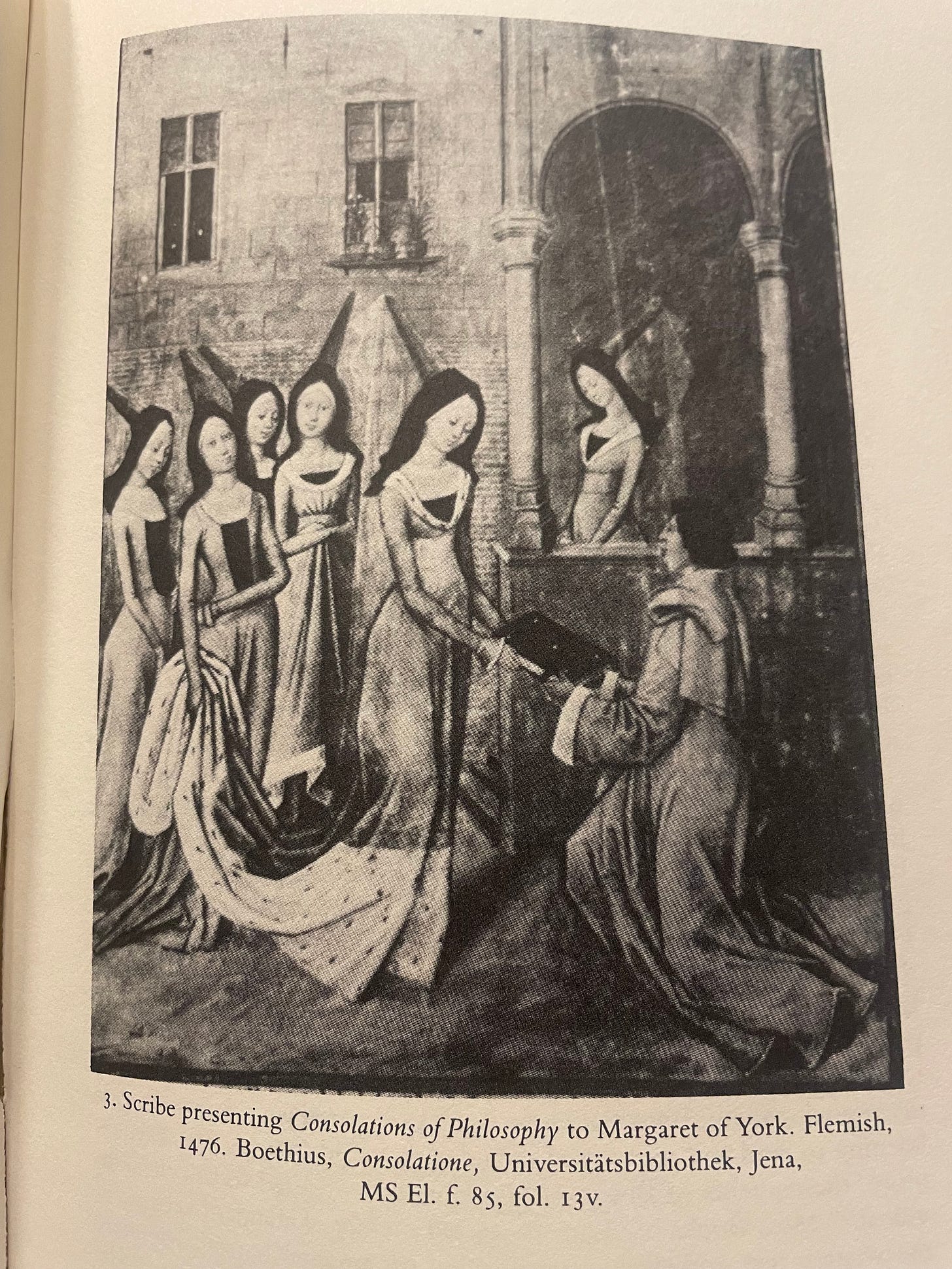

The pervasive power of the single story has promoted the idea that it has always been this way, that the patrilineal system of patriarchal Christianity is something natural and not something nurtured. Yet the “Sachsenspiegel [The Mirror of the Saxons], a collection of Saxon custom laws first compiled by Eike von Repgow in about 1215” makes evident that words have not only long influenced women, but belonged to them. “The text enumerating items to be passed from woman to woman specifically includes all books connected with religious observance. An additional clause in the 1279 version that remained in later editions added that these devotional books were to be inherited by women, because it was women who were accustomed to reading them.”7 Moreover, this custom wasn’t solely confined to Sachsenspiegel areas, as made evident through the survival of a Dutch Book of Hours which bears the names of six generations of women, indicating a Western European parallel.8

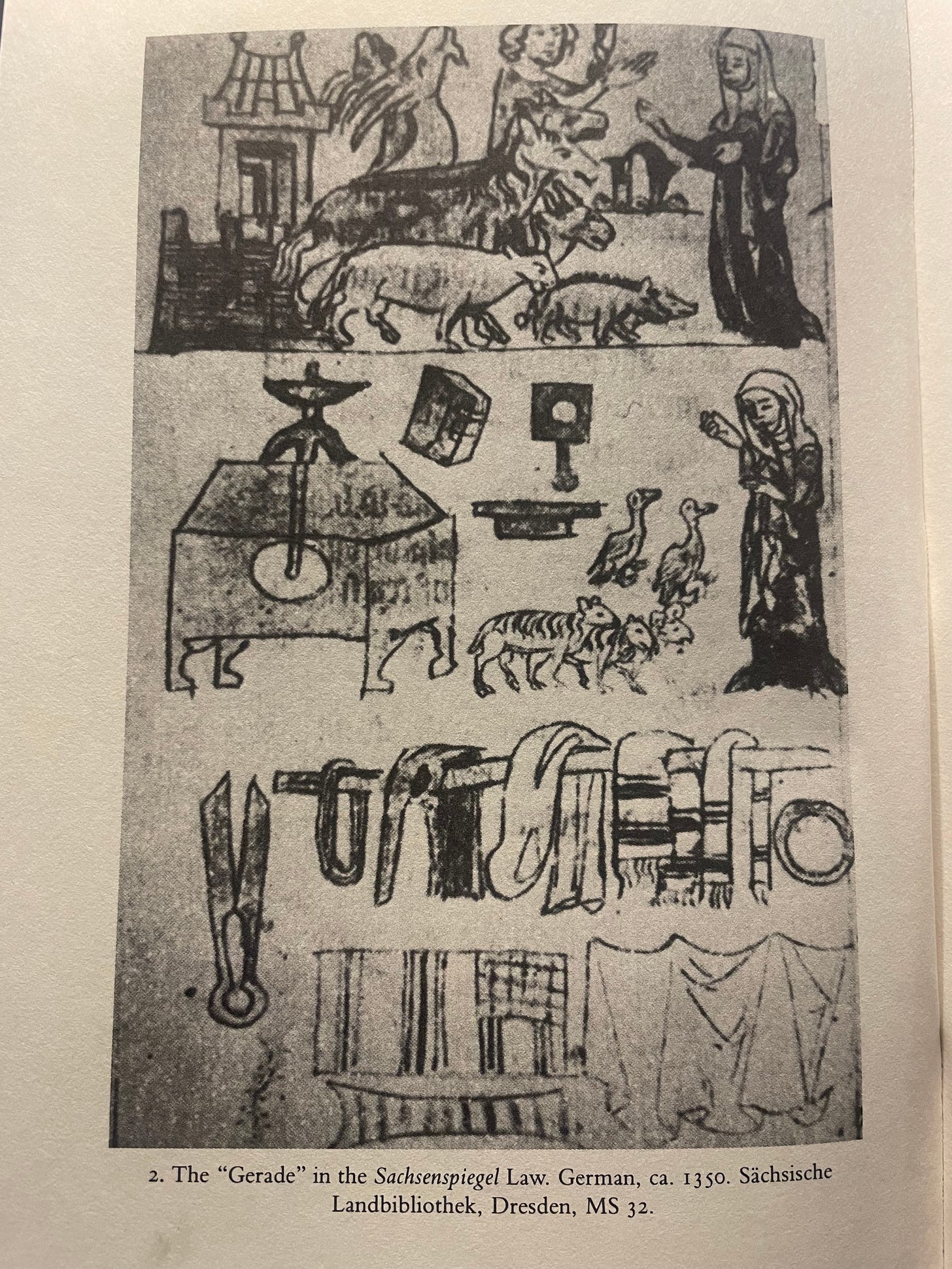

“Women played an important role in teaching, in translating, and in loosening the hierarchical bonds of church control through their close and private relationship to religious books.”9 Books such as the individual, often matrilineal, Book of Hours allowed for private spiritual practices, offering flexibility outside the confines of the patriarchal church structure. In 2021, historian Kate McCaffrey uncovered that a group of women—Elizabeth Hill, Elizabeth Shirley, Mary Cheke, Philippa Gage, and Mary West—had safeguarded Anne Boleyn’s custom Book of Hours after her unjust execution in 1536 by Henry VIII. “It is clear that this book was passed between a network of trusted connections, from daughter to mother, from sister to niece. If the book had fallen into other hands, questions almost certainly would have been raised over the remaining presence of Anne’s signature. Instead, the book was passed carefully between a group of primarily women who were both entrusted to guard Anne’s note and encouraged to add their own. In a world with very limited opportunities for women to engage with religion and literature, the simple act of marking this Hours and keeping the secret of its most famous user, was one small way to generate a sense of community and expression.”10 Tiny acts of feminism, everywhere.

Though executed by a patriarch hell-bent on erasing her presence in the historical annals, the women in Anne’s life ensured the continuation of her existence through the preservation of her private book of spirituality. Women witnessing women. These women risked their lives and livelihoods to preserve women’s words, protecting Anne’s legacy from Henry’s single story. Albeit extraordinary, the patriarchy has rendered stories such as this all too common.

During the Second World War, seven and a half centuries after the death of the incomparable Hildegard of Bingen, the survival of her canon was under threat of destruction. The director of the State Library of Wiesbaden had the Reisencodex moved “hundreds of miles east to Dresden along with another of Hildegard’s most precious manuscripts, a priceless copy of her major work Scivias, containing illuminations that Hildegard herself had a hand in.”11 Regardless of the efforts to keep the collection of priceless medieval works safe, in 1945 Dresden was destroyed by Allied bombs, and the vault which held Hildegard’s surviving works was pillaged, leaving only the Reisencodex behind, the bulkiness of the work disguising it’s immense value.

Because Dresden was in Soviet occupied territory, under accordance of Soviet direction, any “first-class artefacts found in Russian-held German territories became the property of the state.” Hildegard’s work had been proudly preserved in the Rhineland, her home, for 800 years: having once been carried across the Rhine and hidden by nuns of Hildegard’s order during the Thirty Years War of 1618 through 1648 to ensure it’s survival. All to become property to a repressive state, potentially to be lost forever. But women intervened.

Medievalist Margarete Kuhn, who lived in the American sector of West Berlin, was able to legitimately request the Reisencodex under the guise of needing to photograph the impressive manuscript for her position. Margarete then smuggled the book to her American friend Caroline Walsh, who “hid the manuscript on her person and took it via train and car to the nuns of Hildegard”,12 ensuring not only the survival of a priceless manuscript, but the continuation of Hildegard’s works, which directly defied the false-notion of male-supremacy upon cultural influence. If women had still been denied access from education, Hildegard’s words may have been lost from memory forever.

Gatekeepers of Language

In her 2009 TED talk The Danger of a Single Story, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie said “It is impossible to talk about the single story without talking about power. There is a word, an Igbo word, that I think about whenever I think about the power structures of the world, and it is "nkali." It's a noun that loosely translates to "to be greater than another." Like our economic and political worlds, stories too are defined by the principle of nkali: How they are told, who tells them, when they're told, how many stories are told, are really dependent on power.” And the patriarchy has long recognized that to maintain power, it must control the consumption and distribution of knowledge. For if we were to read a sentence such as “girls outside of the cloister were deliberately unschooled in Latin” and encouraged to ask the second question of “who deliberately withheld the girls from learning Latin and why?” the risk of exposure could lead to the recognition that another reality, beyond patriarchy, is possible.

In one Maryland county, 67% of the authors on the banned list are women13, and according to the American Library Association, “titles representing the voices and lived experiences of LGBTQIA+ and BIPOC individuals made up 47% of those targeted in censorship attempts”14 across the country. To believe this censorship is simply a modern morality crusade is to fall for the patriarchal single story, because “current arrangements are historically produced.”15 And if we are going to change our oppressive reality, then we must not only continue to uplift the words of women, but intentionally witness and protect the words of the most marginalized among us.

Our interconnectedness will lead to our independence.

Further Reading/Watching/Listening

To learn more about Hildegard:

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s TED talk, The Danger of a Single Story, is so incredibly powerful, I highly recommend spending the 18 minutes to witness her words.

Abolition. Feminism. Now. by Angela Y. Davis, Gina Dent, Erica R. Meiners, and Beth E. Richie is an incredible call-to-action on the power of imagining a better future for ourselves.

Everything

writes moves my soul. Her piece To leave a trace is a testament to women’s words.

I highly encourage you to witness

’s words and hold space for the devastating histories that have been systemically discarded to promote the single story.

Yes, the governor of Florida did say that

https://www.ala.org/advocacy/bbooks/book-ban-data

https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_ngozi_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story

Ibid.

Angela Y. Davis, et al. Abolition. Feminism. Now Haymarket Books, 2022.

Bell, Susan Groag. “Medieval Women Book Owners: Arbiters of Lay Piety and Ambassadors of Culture.” Signs, vol. 7, no. 4, 1982, pp. 742–68. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3173638.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

https://www.hevercastle.co.uk/news/new-research-anne-boleyn-prayer-book/

https://schoolofphilosophy.org/blogs/philosophy-blog/hildegard-of-bingen-1098-1179

Ibid.

https://cnsmaryland.org/2023/10/12/challenged-books-in-carroll-county-largely-written-by-women-feature-lgbtqia-characters/

https://www.ala.org/advocacy/bbooks/book-ban-data

Angela Y. Davis, et al. Abolition. Feminism. Now Haymarket Books, 2022.

GAWD alive this entire post will need to be read again (and again) 🔥

This paragraph: ‘The Palestinian poet Mourid Barghouti writes that if you want to dispossess a people, the simplest way to do it is to tell their story and to start with, "secondly." Start the story with the arrows of the Native Americans, and not with the arrival of the British, and you have an entirely different story.’

As a South African, in Britain, I cannot stress enough how far into their ignorance Brits will remain rooted by calling out SA racism without delving into the white supremacist colonialism they brought to Africa in the first place. The ‘whataboutism’ is astounding.

Like many, I’ve wrestled with understanding the nature of power throughout my life. I’ve read the Maya Angelo quote so many times but just now has it really clicked. The level of awareness and embodiment of power mostly by men as they actively suppress people and ideas requires intense meditation to capture. The small intuition we have of a power-based person. The feeling of being a bit uncomfortable around them. That merely scratches the surface of what is truly a mountain of controlling and destructive energy/behavior. Listen to men when they reveal their power. Then do everything to avoid their games and maintain your own.

The violence of control and oppression is birthed from the same intense destructive energy of murder and rape. I get that it’s kind of an intense thing to say but it’s true. I’ve witnessed both and now really see oppression in the same category.

I’m sure the story your daughter’s teacher told with her body language as well as her words was intense. Having your passion and life’s work suppressed by a man who is not misguided but intentionally violent is a strike to the spirit that can only be healed with a return to balance and free flow of information. The only viable approach I see is building robust alternative school options and voting. Anything else is playing at their game