2023 - Alice Wong

While promoting her memoir, The Year of the Tiger, disability activist and founder of Disability Visibility Project Alice Wong urged readers to move beyond allyship and into action. Plainly stating “we don’t need allies; we need co-conspirators. We need people in power to change policies and practices. Budgets are a reflection of values.”1

1990 - The Capitol Crawl

On March 12, 1990, well over a thousand people marched from the White House to the U.S. Capitol building advocating on behalf of all Americans, disabled or not, to ensure disability protections were codified into our systems of power. This protest highlighted the sheer inaccessibility of most public spaces within the US—because much like the antiquarian world that Aristotle occupied some time ago, our modern one sees abled-male-body as the default, all constructs and considerations are then composed around that standard. The Crawl sought to disrupt that.

Just a few months after the Capitol Crawl, H.W. Bush would sign the ADA into law.

But disability activists were fighting for representation, accessibility, and visibility long before this particular protest. In the 70s, Judy Huemann organized a 28-day sit in at the San Francisco HEW building. This disruption of daily commerce and everyday movement, amplified by multiple staged sit-ins around the country, was meant to be an unavoidable reminder that “the inferior social and economic status of people with disabilities was not a consequence of the disability itself, but instead was a result of societal barriers and prejudices”—because of the efforts of activists, disability became a protected status.2

1981 - bell hooks

The 80s would see a handful of publications from Black feminist bell hooks, with her pioneering and poignant Ain’t I Woman hitting print in 1981. Within it she wrote:

“When the contemporary movement toward feminism began, there was little discussion of the impact of sexism on the social status of black women. The upper and middle class white women who were at the forefront of the movement made no effort to emphasize that patriarchal power, the power men use to dominate women, is not just the privilege of upper and middle class white men, but the privilege of all men in our society regardless of their class or race.”3

Alongside calling out the harm perpetuated by white feminism in a brutally honest way, hooks’ feminism would encompass liberation for men too—coining the term soul murder, which she described as the first lesson a boy learns in patriarchy. “He learns that his core feelings cannot be expressed if they do not conform to the acceptable behaviors sexism defines as male.” As Rachel Chapman said of her now deceased friend, “[hooks] was writing about what it means to be young and Black and angry and seeing clearly the thin line between being mad and madness, between radical action and personal self-destruction.”4

Black feminist professor and civil rights leader Kimberle Crenshaw coined the term intersectionality in 1989 to describe the compounding modes of oppression which result in overlapping forms of discrimination. As Patricia Hill Collins aptly wrote in Black Feminist Thought: “Intersecting oppressions of race, class, gender, and sexuality could not continue without powerful ideological justifications for their existence.”

1979 - Audre Lorde

Preparing to stand before the gathered academics attending the inaugural New York University Institute for the Humanities conference the following year, Audre Lorde penned the following lines:

“It is a particular academic arrogance to assume any discussion of feminist theory without examining our many differences, and without significant input from poor women, Black and Third World women, and lesbians. And yet, I stand here as a Black lesbian feminist, having been invited to comment within the only panel at this conference where the input of Black feminists and lesbians is represented. What this says about the vision of this conference is sad, in a country where racism, sexism, and homophobia are inseparable.”

Audre Lorde’s brutal honesty emphasized the necessity of intersectionality a decade before the term existed, but it also stressed the importance of a society built beyond the tight grasp of patriarchal violence.

“Those of us who stand outside the circle of this society’s definition of acceptable women; those of us who have been forged in the crucibles of difference — those of us who are poor, who are lesbians, who are Black, who are older — know that survival is not an academic skill. It is learning how to stand alone, unpopular and sometimes reviled, and how to make common cause with those others identified as outside the structures in order to define and seek a world in which we can all flourish. It is learning how to take our differences and make them strengths. For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change. And this fact is only threatening to those women who still define the master’s house as their only source of support.”5

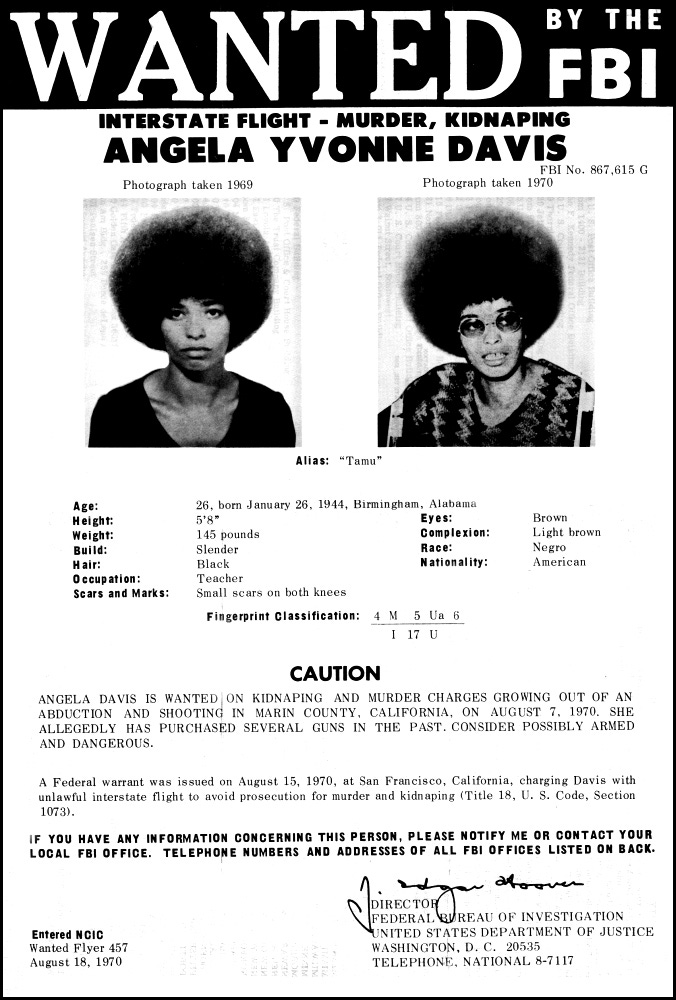

1971 - Angela Y. Davis

Thousands worldwide organized to free Angela Davis after she had been placed on the FBI’s top ten most wanted list and arrested shortly thereafter. Though of course the circumstances were vastly different than the current cultural fixation, this too was a stark and brutal reminder of who is held accountable for (gun) violence within a violent nation enthralled with guns.

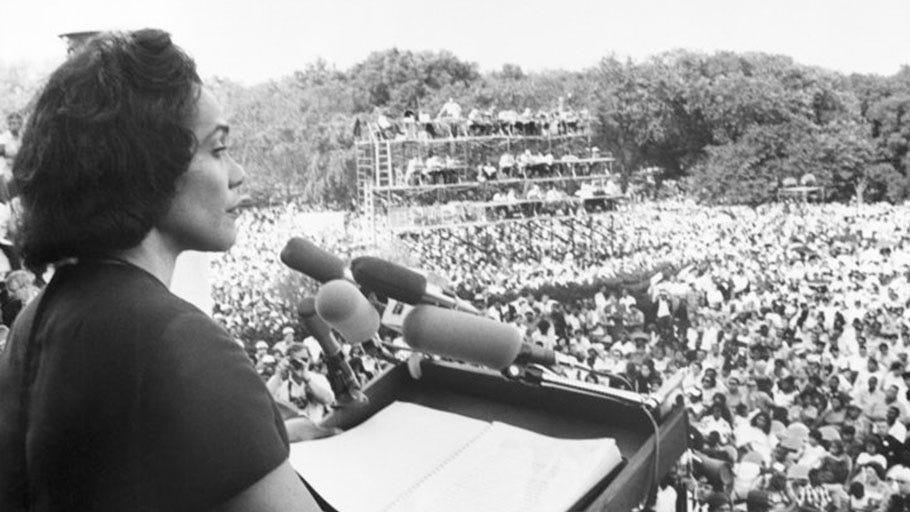

1968 - Coretta Scott King

Just three weeks after the assassination of her husband, Coretta Scott King spoke in front of an assembly of activists for peace in a New York gathering.

“There is no reason why a nation as rich as ours should be blighted by poverty, disease and illiteracy. It is plain that we don’t care about our poor people, except to exploit them as cheap labor and victimize them through excessive rents and consumer prices. Our congress passes laws which subsidize corporation farms, oil companies, airlines and houses for suburbia. But when they turn their attention to the poor, they suddenly become concerned about balancing the budget and cut back on funds for Head Start, Medicare and mental health appropriations. The most tragic of these cuts is the welfare section to the Social Security amendment, which freezes federal funds for millions of needy children who are desperately poor but who do not receive public assistance. It forces mothers to leave their children and accept work or training, leaving their children to grow up in the streets as tomorrow's social problems. This law must be repealed, and I encourage you to join welfare mothers on May 12th, Mother's Day, and call upon congress to establish a guaranteed annual income instead of these racist and archaic measures, these measures which dehumanize God's children and create more social problems then they solve.”6

1861 - Harriet Jacobs

In 1861, a Black abolitionist feminist who experienced enslavement herself published her autobiography Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. In it, Harriet Jacobs brutally outlines the impossibility of white supremacist patriarchy and the treatment of Black bodies within. Not only did she bring sharp attention to the devastating realities of rampant sexual assault experienced by enslaved Black women, she highlighted how white folks continually relied on enslaved Black bodies to meet the emotional needs Patriarchy neglected while they simultaneously placed blame on those very bodies for the faults of a society they did not create nor chose to participate in.

One might say Harriet Jacobs faced white supremacist patriarchy with brutal honesty.

1845 - Anarcha

Though her abuser would be hailed The Father of Gynecology, Anarcha, an enslaved woman in Montgomery, endured upwards of 30 gynecological surgeries inhumanly conducted by J.M. Sims throughout the 1840s. Anarcha’s forced sacrifice still informs medicine today, but I wonder, is that what progress is meant to look like?

1641 - Anna Maria van Schurman

Dutch scholar Anna Maria van Schurman published her book titled The Learned Maid; or, Whether a Maid may be a Scholar?7 Within it she argues that women possess the same form as men in regards to reason and learning, citing idleness and lack of education as catalysts of vice. Much like the suffragists that would come later, Anna Maria van Schurman’s feminism was sorely lacking, as she didn’t advocate for education for all and was against education for the poor. In regards to white feminism, not much has changed as we hail the likes of Ballerina Farms as representative of the movement in any real way.

1622 - Marie de Gournay

Influenced by the women before her, Marie de Gournay published The Equality of Men and Women in 1622, which argued that men and women possess the same virtues as both were created by the same maker.

“Happy are you, reader, if you do not belong to this sex to which all good is forbidden.”8

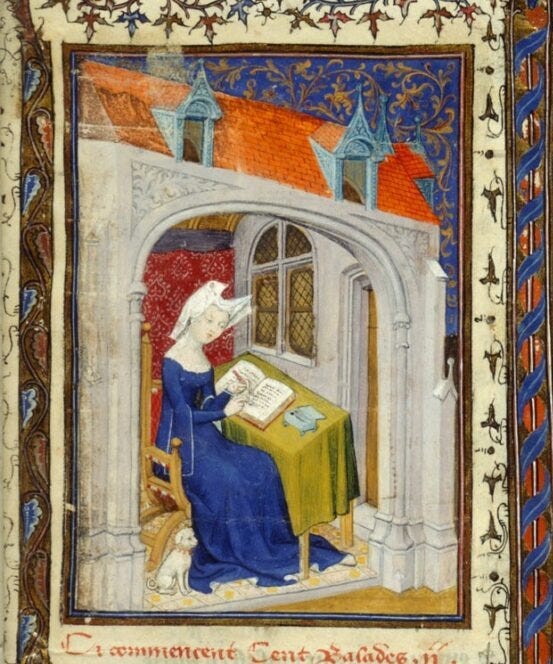

1405 - Christine de Pizan

As someone who loves to shade Aristotle and the grip his 2,000 year old binary thinking has on our modern reality, I greatly admire a woman throwing even more heavy-handed shade some 600 years ago.

The Book of the City of Ladies, written by Christine de Pizan in 1405, introduces countless historical women who had greatly impacted the development of both culture and the world at large. In conversation with Reason, Christine says of ‘women like Minerva, Ceres, and Isis’:

“…for it seems to me that the teachings of Aristotle, which have so greatly enriched human knowledge and are rightly held in such high esteem, put together with all those of every other philosopher who ever lived, are not worth anything like as much to humankind as the deeds performed by these ladies, thanks to their great ingenuity.”9

An important note on placing Christine back into her time—the very purpose of City of Ladies was to engage with the contemporary literary debate while publicly asserting an argument against the reinstitution of an archaic Salic Law. Within her book Christine sought to challenge the idea that women were unfit to rule by creating a prosperous city that could only be so because a woman ruled.10

1322 - Jacqueline Felice de Almania

Women advocating on behalf of women within a patriarchal society is a long held practice—long before words such as ‘feminism’ or ‘intersectionality’ existed. Hauled in front of French judges in the Autumn of 1322, Jacqueline fought for women’s personhood and agency in an argument she likely knew was long lost.11 “In her own defense, Felicie argued fervently for the right of wise and experienced-even if unlicensed-women to care for the sick. With even more spirit she asserted that it was improper for men to palpate the breasts and abdomens of women; indeed, out of modesty, women might prefer death from an illness to revealing intimate secrets to a man.”12

Idyllic Subversion

Who gets to be the folk hero in Patriarchy?

This question feels as if it has lodged itself into my head-space, reverberating off my memories, tugging at the threads of pages read and stories consumed. It has been with me as a constant companion this last month, an unavoidable thought as the collective conversation swirls around within, further clouding and only somewhat clearing the already pondered. Who gets to be a folk hero in Patriarchy?

The intentionally constructed conflation between patriarchal gender norms with the concept of ‘human nature’ allows for only one gender to access a rage that is viewed as socially productive. As my sister-in-feminism,

wrote in a recent piece “the erasure of women’s history was a deliberate effort to uphold the power structures of patriarchy. Historian Gerda Lerner aptly captured this in her seminal work, The Creation of Patriarchy: “To be without history is to be trapped in a present where oppressive social relations appear natural and inevitable.”In patriarchy, anger and rage belong to men. Endless accounts of domination cluttering our educational environments provide much evidence here, as Barbara W. Tuchman partially argues within The March of Folly. Opening with a poignant observation, Barbara notes, “a phenomenon noticeable throughout history regardless of place or period is the pursuit by governments of policies contrary to their own interests. Mankind, it seems, makes poorer performance of government than of almost any other human activity.”

Considering the Latin roots of history refer only to the formal documentation of historical events—which outside of sparse epigraphical evidence of pre- and non-patriarchal societies were exclusively crafted within the gate-kept patriarchal spheres of the church and secular education—one could argue that patriarchal governments are unable to govern in any way other than contrary to their own interests.13 Subjugation generates resentment, and under Patriarchy, all are subjugated—it is impossible to manifest any other reality within a system inherently hierarchical. To this day histories of peoples outside of European cultures are still regarded as pre-history, even if coinciding on a historical time-line with a Eurocentric event as they were outside the scope of European (male) chroniclers and thus neglected in the considerations of human nature. To simply state it, history was written by and for The Patriarchy to promote patriarchal adherence.

We are only just beginning to understand that the lived reality of the past was rife with women subverting contemporary patriarchal ideals as we are too often denied evidence of these women within demonstratively andro- Euro- centric histories. Women of the past that subverted societally upheld standards were instead castigated to the margins of literature; they were the witches, the crones, the hags, they were the ones without any real power in their contemporary culture, yet we were taught to fear them through the folk stories generationally shared. They were the women subverting patriarchal authority to address the very shortcomings that same authority imposed upon their society, and for that, they were forcefully forgotten.

Within a poignant pamphlet titled the 7 P’s of Men’s Violence, Michael Kaufman writes:

“[M]ale-dominated societies are not only based on a hierarchy of men over women but some men over other men. Violence or the threat of violence among men is a mechanism used from childhood to establish that pecking order. One result of this is that men “internalize” violence – or perhaps, the demands of patriarchal society encourage biological instincts that otherwise might be more relatively dormant or benign. The result is not only that boys and men learn to selectively use violence, but also, redirect a range of emotions into rage, which sometimes takes the form of self-directed violence… What gives violence its hold as a way of doing business, what has naturalized it as the de facto standard of human relations, is the way it has been articulated into our ideologies and social structures.”

In patriarchy, we praise those that act individually without questioning why they didn’t first attempt to access their goals through acts of non-violence. We glorify an individual’s violent act(s) against a violent system, presenting it as an act of defiance against the system; As if patriarchy hadn’t always allowed them access to violence, as if the very system they are said to be confronting isn’t violent and predicated upon that violence. We don’t ask if they’ve rallied their community to recognize and subvert Patriarchal influence within their everyday. We don’t question why they never utilize their access to patriarchal power to enact solutions possessing any sort of longevity, as Alice Wong desperately urged. We accept individual acts of patriarchal violence and praise the blip of subversion without adjusting our own participation within the systems that harm us.

As Audre Lorde boldly stated from behind that podium in 1980: “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change. In our world, divide and conquer must become define and empower.”14

If women were allowed to become folk heroes then the name Jeanne de Clisson, a noblewoman turned pirate in early 14th century France, would be widely known.15 Instead, we live in a reality where you’d be hard-pressed to find a Western-educated individual that doesn’t know the names Robin Hood or King Arthur—dudes that pedaled more within the realm of the mythological than within actuality—while having never heard of Jeanne. If we were taught of Jeanne, we would have been taught that women have long held the agency to disrupt patriarchal power—so much so that rivaling kings sought allyship within her due to those skills of disruption via patriarchal violence.16 If we were taught of Jeanne, we’d have been taught that women could command the attention of troops, crews, and cities alike, instead, we have been generationally assured that stealing from the rich to give to the poor—without ever questioning the systems that both produce and allow poverty—is the real heroic act worthy of idolization. Though Jeanne utilized patriarchal violence to achieve power, her story threatened the assumed naturality of patriarchal gender roles and the inherent meekness of the female gender. Thus, she has been forcefully forgotten, castigated to the margins of literature.17

In the face of Luigi Mangione’s act of patriarchal violence, I admittedly welcome the forthcoming conversations of class-solidarity from every side of the American political ecosystem. But if your dreams of a better future do not allow space for conversations around gender- or racial- solidarity and a realization of intentional equity, then all you are doing is recreating white supremacist patriarchy through a socialist or communist paradigm. There is a reason Claudia Jones’ biographer, Carole Boyce Davies, titled her work Left of Karl Marx when writing of a woman who demanded attention be brought to the “super exploitation of black women.”18 As Marilyn French documented in 1992 “women in socialist nations have long maintained that they work two jobs to men’s one.”19 Patriarchy is patriarchy is patriarchy, isn’t that what Shakespeare said?

Until we challenge the very real threat Patriarchy and patriarchal gender roles hold over all of us—the tools of our master’s house—I fear all we will do is recreate some rendition of oppressive patriarchy that has already been realized within human history; A moment frozen in time that allowed the conditions for the complete negation of women.

If the creation of a new society is predicated upon patriarchal violence, then all we are doing is creating yet another system that not only allows patriarchal power via violence, but believes it a necessary function of existence.

We deserve to dream beyond patriarchy.

To my paid subscribers: You make this space and this research possible. Your support has allowed access to further research that may have been outside of my reach prior—this is a gift I value greatly and will cherish continually. Thank you for the gift of your support. Thank you for the gift of your time. Thank you for the gift of learning. 💜

https://nursing.ucsf.edu/news/disability-and-health-care-conversation-activist-alice-wong

https://ability360.org/livability/advocacy-livability/history-disability-rights-ada/

hooks, bell. Ain't I a Woman : Black Women and Feminism. New York :Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2015.

https://www.kuow.org/stories/here-s-what-bell-hooks-friends-and-colleagues-want-you-to-remember-about-her

Lorde, Audre. Sister Outsider : Essays and Speeches. Trumansburg, NY :Crossing Press, 1984.

Until The Last Gun Is Silent: Transcript of a Speech Delivered by Coretta Scott King at a Peace Rally on the Sheep Meadow in Central Park, New York City, on April 27, 1968

Clarke, Desmond M.. Anna Maria van Schurman and Women's Education. Revue philosophique de la France et de l'étranger, 2013/3 Tome 138, 2013. p.347-360

de Gournay, Marie. Égalité des Hommes et des Femmes, 1622

The Book of the City of Ladies, Christine de Pizan, 1405 - Translation and edits by Rosalind Brown-Grant

McRae, Joan E.. Literary Debate in Late Medieval France. University Press of Florida, 2024

Minkowski WL. Women healers of the middle ages: selected aspects of their history. Am J Public Health. 1992

https://www.oed.com/dictionary/history_n?tab=etymology#1664519

Lorde, Audre. Sister Outsider : Essays and Speeches. Trumansburg, NY :Crossing Press, 1984.

Want to learn more about Jeanne de Clisson? She will be a feature in an upcoming piece — be sure to subscribe to be notified!

Jeanne de Belleville: The Life of Jeanne de Clisson, by Émile Péhant. An English Translation and critical introduction by Ellen O’Brien.

Sumption, Jonathan. The Hundred Years War, Volume 4: Cursed Kings. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017.

Jeanne de Belleville: The Life of Jeanne de Clisson, by Émile Péhant. An English Translation and critical introduction by Ellen O’Brien.

Boyce Davies, Carole. Left of Karl Marx : The Political Life of Black Communist Claudia Jones. Durham: Duke University Press, 2008

French, Marilyn. The War against Women. Summit Books, 1992.

Have you read the graphic novel The Legend of Auntie Po? It’s Paul Bunyan reimagined as a Chinese woman in California.

Love this. I read City of Ladies years ago--I think I need to read it again!