A patriarchal phallusy: Believing you can play devil’s advocate in regards to gender inequality1. You either see women as human beings deserving of equal rights, agency, autonomy and dignity, or you don’t. And if you don’t, what does that make you? Men’s rights groups keen on upholding the dominator model declare patriarchy as the natural order of things, yet patriarchy has only existed for 3% of the total time homo sapiens have been erect upon our Mother—isn’t it wild how much of our man-made language is phallic in nature? Patriarchy isn’t natural, it is nurtured. Upheld anew by every generation through oppressor-benefits and societal pressures, the smallest transgression from traditional masculinity shamed and publicly eviscerated to act as behavioral guideposts to us all. If patriarchy were natural, it wouldn’t require endless physical effort to remain intact: constant wars, continual litigation, ceaseless coverage of the talking-heads. If it were natural, men wouldn’t be making the tragic choice to opt-out of patriarchy by taking their own lives at an alarming and ever increasing rate.2 None of this is natural, and it is hurting us all.

Long before the existence of words to describe such actions, women have pushed against the patriarchy’s rigid gender roles, witnessing first-hand the oppressive nature inherent of a society that uplifts one gender to the denigration of all others.3 The exclusion of women from education is often framed as an accidental outcome of societal progression, yet the devastating headlines pouring out of Taliban held Afghanistan are a modern reminder that the marginalization and oppression of women has always required a conscious and constant effort.4 As the UN pointed out last year, “the world is failing 130 million girls denied the human right to education – a fundamental, transformative, and empowering right for every human being. Universal access to quality education enables individuals, communities, countries and the world to build wellbeing and prosperity for all. All States have made commitments to realise the right to education for all, but fewer than half of the world’s countries have achieved gender parity in primary education. Denying girls and other vulnerable groups their fundamental right to education is discrimination at its most debilitating.”5

Withholding education from girls, women, and other vulnerable groups not only deprives the world of the thoughts and ideas of more than half the population, ultimately disrupting human evolution, it also allows for the unchallenged continuance of the single story.6 A single story which promotes white supremacist capitalistic patriarchy7 as the superior method to govern society while actively minimizing the harm inflicted upon us all.8 A single story which allows a white man to confidently type in a stranger’s comment section “the world doesn’t seem euro-centric, it is euro-centric”, and believe he is right, reminding us once again that bell hooks said it best when she wrote “nothing discounts the old antifeminist projection of men as all-powerful more than their basic ignorance of a major facet of the political system that shapes and informs male identity and sense of self from birth until death.”9 When women gain access to education, teen birth-rates go down. When women gain access to education, women’s history and cultural contributions become centralized. When women gain access to education, a world beyond the patriarchal nuclear family becomes available. And this just won’t do for a society keen on promoting the idea that women are simply incubators for the male seed.

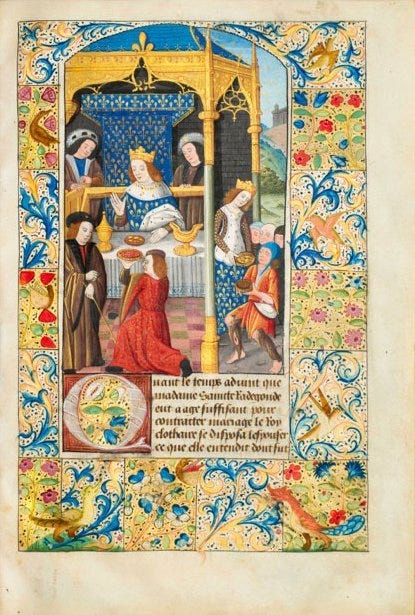

In the Middle Ages—at least, in Western/Christian Europe—women had few access points to education, and even fewer access points to the written word.10 Women born of privilege were often given an informal education organized around the roles they were expected to fulfill in the future: mother and wife. History often recording all others simply as the Baker’s wife, the Brewer’s wife, or the Captain’s wife, wholly negating the well-documented reality that they too were bakers, brewers, and dispensing orders alongside, and often in place of, their husbands. Outside of unearned privilege, one place a woman could access education was through a role at the Church, which usually required a vow of chastity and a lifetime devotion. Because of this Christianized gate-keeping of education, the Church ensured folks were educated in the ‘virtues’ of Christian patriarchy, learning the stories of Great Men alongside the denunciation of women’s inherent sinfulness.

Yet, even with an education heavily seasoned in patriarchal propaganda, the women in the medieval church often subverted patriarchal control through writing their own works in the vernacular language and not within the patriarchy preferred and praised Latin.11 Writing in Middle English or Middle High German allowed women’s work to be accessible to a wider audience, not crafted solely for church consumption, and often explored themes and stories intentionally excluded from the church’s structured education. These women probed into the lives of women-past, they peeled back the layers of their own womanly experience, and they often gender and genre-bent to create something entirely new, ushering in an early renaissance in exclusive circles. These women often ensured other women’s stories were preserved while simultaneously probing into proto-feminist themes, questioning the oppressive structure of the patriarchy (again, long before such words existed.) Women such as Hildegard of Bingen who vocally celebrated the delight of femininity. Women such as Christine de Pizan who not only saw right through men’s projected hatred of women but believed women to be nobler creatures than man as they were created inside of Paradise, and not just of dust.12

During the month of March, Women’s History Month here in the US of A, I celebrated by sharing ‘a women a day’ via the Notesphere. But these women deserve more than a day, more than a month. They deserve to be in the history books, highlighted for the immense influence they wielded, their ingenious creativity, and the patriarchal-contradicting questions they asked long before we had the language to explain such themes and thoughts. While I personally can’t change the history books, I can preserve these women’s words and make their names and stories accessible to those seeking them. Ultimately, this will be a post in three parts: the women from Notes 1-15, 16-31, and then a separate exploration of medieval women of color whom also influenced the world with their words and wisdom, neglected by Euro-centric education in a colonized world.

Thank you to every single person that shared these women’s stories last month in the Notesphere. To every person whom asked questions, expressed gratitude, and learned right alongside me, thank you. I feel honored to witness these women with you.

1. Vibia Perpetua - circa 181 CE-203 CE

Vibia Perpetua was martyred on March 7th, 203 CE, no older than aged 22. We know of Perpetua’s life and death through her dairy, “as she left it written with her own hand and in her own words.” Her diary gives us the account of her final days imprisoned for her Christian beliefs in pagan Roman Carthage alongside a declaration of doctrine in the form of dialogue. However, we only know Perpetua’s name and age due to a redactor adding this information post-martyrdom.

Born around 182 CE, Perpetua defied societal norms by converting to Christianity. Despite facing intense persecution and the threat of death for her beliefs, she remained steadfast in her faith. Perpetua's unwavering courage and dedication to her religion made her a symbol of resistance and strength, highlighting how galvanizing self-conviction can truly be.

The importance of Perpetua’s writing as an example of women’s writing from antiquity has long been overshadowed by it’s residency within Christian history. 19th Century English scholar and churchman J. Armitage Robinson labeled Perpetua’s writing style as “simple”, chiefly compared to the obviously male redactor’s more eloquent style of writing. “[Robinson] concludes it is “due to two principal causes: first the constant use of the simplest of conjunctions; and secondly the incessant repetition of the same words and phrases.””13 Yet he never considers the context. This is a woman—who, because of gender, was systematically denied the highest echelons of education—awaiting persecution, journaling her experience of familial separation, including from her infant son, while enduring hostile conditions within imprisonment. She was writing through starvation, harassment, and cold-turkeying lactation, which brings about mind-numbing discomfort for those unfamiliar.

Robinson’s assumption that her words were written for his consumption is driven through the patriarchal social construct of male-superiority. He calls her simple and repetitive, but her diary reads as a diary should, mentioning the passing of days: “for the few days…”, “after a few days…”, “a few days later…”. She was writing words for herself, documenting her experience for herself, not setting out to be a thought-leader seeking fame and accolades. “Who is the simple one now?” I hear bell hooks asking Robinson.

While Robinson perfectly exemplified patriarchal bias, Perpetua’s writing and personal character highlighted the strength of matriarchal thought and community: "Stand fast in the faith, and love one another."

So, let us have the moxie of Perpetua and “love one another”, for in community we are stronger.

2. Faltonia Betitia Proba - 4th Century

Faltonia Betitia Proba was born into a wealthy and influential Roman family in the 4th Century and likely received an extensive education made evident by her accomplishment of literature and theology found within her writing. Proba converted to Christianity in adulthood and deeply influenced her praefectus urbi husband and sons, who converted some time after her. (Women’s influence within their own households was as powerful then as it was in Anglo-Saxon England with the likes of Queen Bertha and Queen Æthelburh).

When writing of Mary, Proba omitted Joseph altogether, and many scholars have critiqued Mary’s lack of femininity within Proba’s poem Cento Vergilianus de laudibus Christi, which borrowed verses from Virgil with modifications to tell the stories of both the old and new testament. (Historians seeking confirmation of socialized gender norms to promote patriarchal adherence feels on-brand.)

Proba’s work blended her life as an Anician woman with classical thought and a devotion to theology, showcasing her intellect and creativity alongside her spiritual convictions. Though she did not invent the Cento, her innovative approach to poetry made her a unique voice in the literary landscape of her time, exemplifying the importance of finding your voice and style of writing, for no one can write your words but you.14

Proba’s words are as applicable today as they were in the 2nd century, reminding us that the patriarchy is predicated on violence, a common theme binding us to our antiquarian ancestors.

“From earliest time, leaders had broken sacred Vows of peace - poor men, caught up in a fatal Greed for power. And I have catalogued The different slayings, monarchs' cruel wars, And battle lines made up of hostile Relatives. I sang of famous shields, Their honor cheapened by a parent's blood, And trophies captured from no enemy; Bloodstained parades of triumph "fame" had won, And cities orphaned of so many citizens, So many times. I do confess. It is Enough to bring these errors back to mind.”

3. Egeria - 5th Century

Egeria, who lived during the 4th century, is the original travel writer, documenting her pilgrimage to the holy land in the 380s, providing valuable insight into Christian liturgy and practices of the time. Egeria’s writing has been instrumental in understanding religious customs of the early Christian church, yet she was only credited with her work in the early 20th century.

Egeria’s writing, often referred to as the Itinerarium Egeriae, was first credited to another, Sylvia of Aquitane the patron saint of pregnant people, and though we don’t have a clear picture of Egeria, or whom she was writing to/for, we can ascertain a few details about her life: She could afford extensive pilgrimage with knowledgeable guides, she was well educated in scripture as well as literary use with mastery of Latin, if not also Greek, and was part of a like minded community interested in growing within their own spirituality. Many scholars argue for Egeria’s association with the church, however, lay folks also had access to pilgrimages, especially if they were of the upper/middle classes.

Egeria’s letters are written in Latin and addressed to ‘sorores’, or sisters, which is what has led many to believe she was an abbess, yet it could be just as likely that Egeria was writing to her book-club of sorts: like-minded women engaging in topics that are important to them, guiding them along their own personal journey. There is plenty of evidence that women were drivers of both religious and lay culture, though chroniclers of the time were largely unwilling to identify women’s contribution, which has left later historians falling back on their patriarchal biases and inherited misogyny.15

4. Baudonivia - 6th Century

Women have always told the stories of women.

When women gained access to higher education in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, women’s history began to be re-imagined and re-centered—no longer relegated to the margins or stripped of cultural impact. “In 1983 Florence Buckstaff published an article exploring the legal rights of married women in medieval England”, noting the common theme between the spanning centuries: “the sexes are not equal.” “In subsequent years, other medievalists (mostly women) began investigating the history of women in the Middle Ages: Elizabeth Dixon looking at craftswomen in Paris in 1895; Lina Eckenstein investigating female monasticism in 1896; Annie Abram writing about working women in London in 1916; Eileen Power examining English nunnery in 1922.”16 Women have long understood the need to preserve women’s stories in this patriarchal reality.

In the first decade of 600 CE, Baudonivia, a religious woman in France was tasked with writing a hagiography for the sainted Frankish queen Radegund, whom founded the Abbey of the Holy Cross at Poitiers. Much like modern (mostly women) historians, Baudovinia looked at Radegund as a whole human outside of her socialized gender roles. She “created a portrait of a deeply devout but politically shrewd woman who used her worldly power to sustain the monastery.” A stark contrast from the prior hagiography written on the Frankish queen which focused more on her “deference to authority.” Making it thematically central to his text and view of Radegund, bishop and poet Venantius Fortunatus was unable to discern the person from the socialized gender traits, thus creating yet another biased view of a woman in history.

Like many of us writing about these incredible women from eras-past, Baudonivia felt humbled by the task: ‘I can as easily touch heaven with my fingers as perform the task you have imposed on me.’17

Cheers to the women that have always seen women’s greatness. 🥂

5. Hygeburg of Heidenheim - 8th Century

Like many of the women highlighted thus far in this series, Hygeburg of Heidenheim was established within a religious institution, which was an access point for women to receive education outside of the elite few. An Anglo-Saxon nun who migrated to Bavaria, Hygeburg took up residence at the monastery at Heidenheim where she wrote a hagiography of two kinsfolk: Wynnebald and Willibald.

Writing sometime between 760-780, “Hygeburg was the only known female hagiographer of the period. [Her] writing offers the only extant narrative account from Western Christendom of interactions with Islam in the Holy Land during the eighth century; it also represents one of a handful of accounts from the period after Persian and then Islamic societies governed the region and before the Crusades, in other words from the early seventh century CE until the very end of the eleventh.”18

Hygeburg’s name was unknown until deciphered in the 20th century, yet her writing was invaluable in understanding Christianity and pilgrimage during the Carolingian period.

6. Dhuoda - circa AD 824-844

Unlike the other women highlighted within this series thus far, Dhuoda was not attached to the church—though obviously spiritual, upholding patriarchal Christianity through her writing—she gained access to education, scripture, and literacy through her privilege as a Frankish noblewoman. “Although Dhuoda was married to the most prominent Frankish magistrate at the time, she is not mentioned in any contemporary works from that period except her own.” Patriarchal histories, amiright?

Dhuoda, living in the 9th century, experienced every turn of fortune’s wheel within her lifetime. Living separate from her husband and having her sons forcibly removed from her, Dhuoda felt compelled to write her Liber Manualis, a behavioral guidebook for her son William. “Apart from a few letters, prayers, poems, and lives (usually of abbesses by nuns), women's writings are scarce, and writing by laywomen-that is, by biological mothers-even scarcer. For that reason, as well as its intrinsic interest, Dhuoda's Manual is enormously valuable”

Dhuoda wrote out of a compulsion to protect and influence her son, even from afar, and though her work has spiritual references within it, it is not monastic in spirit. “William was raised to be a soldier, the father of a family, a vassal and a lord. His mother directed him to love and obey his father, to pray for his father's ancestors, to take his place in the line of warriors from which he was descended.”19

“Mother and son alike were born into patriarchy; their choices were limited to the possibility of doing well or badly within that system.”

7. Hrotsvitha - circa 935-973

Born in Saxony circa 935 CE, Hrotsvitha von Gandersheim is considered to be the first woman playwright of the Western world. Hrotsvitha, a canoness at Gandersheim Abbey, wrote plays, poetry, and historical works, showcasing an extensive education.

Hrotsvitha's writing often centered around religious themes and moral lessons, drawing inspiration from classical Roman comedies and tragedies. She is best known for her six plays, which were written in Latin and focused on the lives of saints and martyrs. Her writings were innovative for the time, as she introduced Christian concepts into classical literary forms. As both Katharina M. Wilson and H. Homeyer explored in their respective works, Hrotsvitha’s “wissenschaftliche erörterungen” [scientific discussions] were wholly unique, garnering critique by male scholars for her lack of understanding of the original texts, while amassing praise from feminist scholars for her attempt to depict “laudable deeds and saintly characters worthy of emulation” to influence cultural behavior.20

Though Hrotsvitha lived in a time before words such as feminism or feminist, she was a woman who authored works in hopes of influencing culture. As Sara Ahmed wrote in Living a Feminist Life: “living a feminist life does not mean adopting a set of ideals or norms of conduct, although it might mean asking ethical questions about how to live better in an unjust and unequal world (in a not-feminist and antifeminist world); how to create relationships with others that are more equal; how to find ways to support those who are not supported or are less supported by social systems; how to keep coming up against histories that have become concrete, histories that have become as solid as walls.”21

Cheers to all the women visionaries left behind in patriarchal narratives; we are determined to know your names!

8. Anna Komnene - circa 1083-1153

Anna Komnene, born around 1083, was an influential Byzantine princess, scholar, physician, and historian. As the eldest daughter of Emperor Alexios I Komnenos and Empress Irene Doukaina, Anna was well-educated and known for her intellect, having studied philosophy, literature, and medicine. Alexiad, her historical work which chronicled the reign of her father and the First Crusade, highlighted the important position historians should take, which is too often neglected:

“Whenever one assumes the role of historian, friendship and enmities have to be forgotten; often one has to bestow on adversaries the highest commendation (where their deeds merit it); often, too, one's nearest relatives, if their pursuits are in error and suggest the desirability of reproach, have to be censured. The historian, therefore, must shirk neither remonstrance with his friends, nor praise of his enemies. For my part, I hope to satisfy both parties, both those who are offended by us and those who accept us, by appealing to the evidence of the actual events and of eye-witnesses. The fathers and grandfathers of some men living today saw these things.”22

Anna’s work has been scrutinized for it’s literary flair and recreation of events forgotten, her legacy facing the same gender-associated challenges she would have dealt with during her lifetime. Yet it would be disingenuous to say the Great Men of historical writing didn’t do just the same, usually at the detriment of womankynd. How many true stories/histories have we consumed that have been entirely propagandize, littered with patriarchal phallusies? (And please know I am thinking of Paul Murray Kendall’s description of Elizabeth Wydeville’s cold eyes glaring at Richard from across the table.)

Though it is certain her historical work includes flair, it also offers valuable insights into the Byzantine Empire during her lifetime. Anna passed away around 1153, leaving behind a lasting impact as one of the few female historians of that period.

9. Matilda, Countess of Tuscany - circa 1046-1115

Though today’s medieval matriarch was not a writer herself, Matilda, countess of Tuscany’s patronage of religious, educational, architectural, and medical institutions—as well as cultural influence—garners her inclusion within this list of phenomenal women who left a literary mark on the word, for in her patronage history was preserved and knowledge pursued.

Matilda’s education was both vast and unique for the time, “under the tuition of Arduino della Palude she learned to ride like a lancer spear in hand, to bear a pike as a foot-soldier, and to wield both the battle-axe and the sword.” Matilda was well educated, both in literature and warfare, which would serve her later when she embodied the “strong right arm of the papacy” during the Investiture Controversy, a power struggle between the papacy and the Holy Roman Emperor over the appointment of bishops. Matilda’s support of the papacy led to her excommunication by the emperor.

As a patron, Matilda of Canossa played a key role in the development of Romanesque art and architecture, supporting the construction of churches, monasteries, and other cultural institutions. She also sponsored the education of numerous scholars and intellectuals, helping to preserve and advance knowledge during a tumultuous period in European history.

“Of Matilda the warrior maid, the ruler and the judge, the gracious chatelaine of Canossa we have some knowledge from a contemporary chronicle written in rude Latin verse by Domnizo, a monk of Canossa. Of Matilda the woman, of her personal joys and sorrows, we know little, for on these points Domnizo is strangely silent.” 23This disregard to document the human behind the gender was yet another way the patriarchy has minimized women’s impact as historical cultural drivers. Much like another Matilda—Empress Matilda, daughter to William the conqueror—we know of the movements of women, but not the motives, for in a patriarchy action is praised while emotion is dismissed.

10. Trota of Salerno - 12th Century

(Excerpt from my piece, The Minimization of the Mother)

For nearly 500 years Trota of Salerno’s collection of texts were the definitive guide to all things gynecological. Trota was a “Magistra of Medicine at the School of Salerno, [and] ran a prolific clinical practice.” The access which she and her students had as midwives to pregnant and birthing women allowed them to develop treatments for common wounds such as perineal tearing and uterine ruptures. “[Trota] developed and documented a wide variety of herbal and animal remedies for the prevention and care of infectious wounds. For labor pains, she also developed a variety of opiates, which were extended to deal with general postoperative pain as well.” The ‘climate of tolerance’ that existed within Salerno at this time (circa 11C, but documented long before then) allowed Trota to be informed by “the cultural influences of Arabs, Jews, Greeks, and Romans [which] all coalesced to support intellectual and academic achievements,” as well as providing a setting for other women enthusiastic about learning and healing to take up space. The success Trota was able to achieve—with that impact still felt today in the 21st century—was due to the very thing conservatives are fighting against in 2024: diversity.

Trota’s domination of the gynecological field wanned when “a significant revision by Ambrose Paré’s assistant” was released in the early 1600s. Yet for at least 400 years, her words were the gynecological bible, informing readers of every gender while also becoming the foundation many modern practices are built upon. Yet to reuse Trota’s own word—with a Miley Cyrus spin to it—she never received her flowers. Trota didn’t become the Foremother of Gynecology, nor was that distinction offered to any of the surgical women and midwives hailing from that strip of land for the thousands of years prior to Trota stepping onto the scene.

11. Christina of Markyate - circa 1096-1155

“This Anglo-Saxon woman was born into nobility but chose a path contrary to the conventions of her inherited social class.”24 Christina of Markyate, while in the midst of a tumultuous betrothal forced by her mother, took a vow of perpetual chastity, which she would uphold until her death in 1155. Though not a writer herself, her biography, The Life of Christina of Markyate, was clearly written with her guidance and voice in mind. Often mistaken as an autobiography due to the nature of the writing, Christina may not have been an author herself, but her influence alongside the insight her Vita provides into 12th century English religious practices garners her a spot within this list of formidable medieval women.

Christina, unwilling to break the vow she made with (and for) herself, fled her privileged life and found safekeeping with a hermit for several years. From there she moved to Markyate and lived as a spiritual leader for a small group of religious women. Christina, like Chaucer’s Custance, fought back against her adversaries, unwilling to be the passive receiver of sexual assault medieval women are too often painted as.

Christina chose to become a religious recluse to avoid the shackles of medieval wifedom, and the Vita allows us insight into the challenges faced by women who sought to live a life of intense devotion outside of traditional religious institutions. Discussing her need to overcome her own sexuality, Christina allows a voice to be given to a too often taboo topic: female sexuality.

12. Héloïse - circa 1098-1164

“Heloïse was one of the brightest minds of her time and the first medieval female scholar to critically discuss feminist issues such as marriage and motherhood.”25 Often remembered for her intellectual prowess and her passionate love affair with Peter Abelard, Heloïse’s lived experience was a testament to the challenges faced by women in a male-dominated society. Despite her exceptional intelligence and education, she was ultimately constrained by the societal expectations of her time, which limited her opportunities for autonomy and independence. Patriarchal historians often only valuing her influence upon Abelard and not her writing in its own right, a theme we’ve seen often in this series.

Heloïse's relationship with Abelard, though celebrated in literature and history, also highlights the unequal power dynamics that often exist between men and women, both then and now. While Abelard's reputation and career flourished, Heloïse's own ambitions were stifled, leading her to a life of seclusion in a convent. However, Heloïse's letters to Abelard reveal a woman who was not afraid to speak her mind and challenge the norms of her society, showcasing her resilience and inner strength.

Though under appreciated for far too long, “Recent scholarship has begun to recognize Heloïse, not only for her impressive literary talent, but for her philosophical contribution, particularly in the area of ethics.”26

Read the Letters here: archive.org/details/lettersofabelard00a…

13. Hildegard of Bingen - circa 1098-1179

Born in Germany in 1098, Hildegard of Bingen defied the gender norms of her time by becoming a prominent voice in the male-dominated medieval church. Like the women you and I know, Hildegard was so many things: a Benedictine abbess, mystic, composer, philosopher, polymath, and—though the word would not exist for hundreds of years—a feminist. Hildegard's feminist legacy lies in her boldness to speak out against the injustices faced by women, advocating for their education and empowerment. She believed that women had the same intellectual capacity as men and deserved equal opportunities for spiritual growth and leadership within the church and society.

“Writing in 1150, [Hildegard] provided the first known description of what a female orgasm feels like:

When a woman is making love with a man, a sense of heat in her brain, which brings with it sensual delight, communicates the taste of that delight during the act and summons forth the emission of the man’s seed. And when the seed has fallen into its place, that vehement heat descending from her brain draws the seed to itself and holds it, and soon the woman’s sexual organs contract, and all the parts that are ready to open up during the time of menstruation now close, in the same way as a strong man can hold something enclosed in his fist.

“Hildegard matters, not just for her own extensive contributions to European theology, science, music and art, but also for what she reveals about the vibrant culture of ‘Renaissance’ twelfth-century Germany”27 with a distinctly feminine focus. Hildegard's writings, including her theological works and visionary texts, emphasized the importance of women's voices and experiences. Through her music and art, she expressed her spiritual visions and connected with others on a profound level. Hildegard's holistic approach to health and healing also showcased her understanding of the interconnectedness of mind, body, and spirit, challenging the conventional wisdom of her time.

14. Marie de France - circa 1160-1215

Marie de France, a medieval poet, stands as one of the earliest identified female authors from France, though it is likely she lived and wrote in England at some point within her life. While details about her personal life, such as her precise birth and death dates, remain scarce, it is believed she was literate in French, Latin, English, Breton, and Welsh. Renowned for her lais, a form of brief narrative poetry focusing on courtly love, chivalry, and magic, Marie de France often showcased robust female leads and explored themes of love, loyalty, and bravery. Marie was a pioneer, among the first women to write strictly for literary purposes.

Among Marie de France's notable works are "Lanval," "Bisclavret," and "Yonec," showcasing her distinguished writing style marked by elegance, emotional depth, and vibrant imagery. Today, she is hailed for her impact on medieval literature and her groundbreaking role as a female writer in a predominantly male literary landscape. Her enduring works are celebrated for their timeless themes and captivating storytelling, ensuring her legacy in the realm of literature.

Sometime between 1160 and 1190, Marie wrote of other people’s opinions, reminding us that they are none of our business:

“Those who gain a good reputation should be commended, but when there exists in a country a man or a woman of great renown, people who are envious of their abilities frequently speak insultingly of them in order to damage this reputation. Thus they start acting like a vicious, cowardly, treacherous dog which will bite others out of malice. But just because spiteful tittle-tatters attempt to find fault with me I do not intent to give up. They have a right to make slanderous remarks.”28

Like Marie said, let them speak ill, it’s none of your business.

15. Beatriz de Dia - circa 1140-1212

Beatriz de Dia, also known as Beatriz de Romena, was a medieval trobairitz, a female troubadour, who lived in the 12th century. She was born in the region of Occitania, which is now part of southern France. Beatriz is one of the few known (to history) female composers and lyric poets from the medieval period. She is best known for her song "A chantar m'er de so qu'ieu no volria" (I am forced to sing of what I would not), which is a poignant expression of unrequited love.29

Beatriz de Dia's poetry often explored themes of courtly love, chivalry, and the complexities of romantic relationships. Her works were written in the Occitan language, also known as Provencal, which was a common language for troubadours of the time. Beatriz's songs are characterized by their emotional depth, wit, and musical sophistication. Despite the challenges faced by women in the male-dominated troubadour tradition, Beatriz de Dia's work has endured through the centuries, showcasing her talent and creativity.

Though evidence is scant of the existence of fellow trobairitz, we know they existed, even if patriarchal history doesn’t record that existence. We know of their existence through the words that were created to explain their presence. Edith Borroff, in her article titled Women Composers: Reminiscence and History, wrote: “evidence is obscure in part, consisting at times of such fragile evidence as the many vernacular terms for women that would have had no purpose were there no women for the terms to be applied to. For example, Provencal had not only a term for trobabairitz, a female troubadour—and the famed Cantigas of Alfonso X (C1252-1284) illustrations of both. Old English had terms for both male and female musician (gligmann and gliewmeden), as well as word forms for specific performers (hearpestre, a female harper; timpestere, a female drum player, etc.).

These words would not exist without the existence of people to fill them, for we create words to describe our reality. Though they’ve been lost to history (for now), those women were there: making art and letting their presence be known, even from afar.

This is true in regards to any oppressed group. Oppression is well documented, if you are choosing to advocate against equity and for oppression, it is important you ask yourself why and sit with what type of person that makes you.

https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/suicide-data-statistics.html

The Book of the City of the Ladies, Christine de Pizan, translated by Rosalind Brown Grant

https://www.politico.com/news/2022/12/20/afghanistan-women-taliban-education-00074899#:~:text=It%20is%20the%20latest%20edict%20cracking%20down%20on%20women's%20rights.&text=KABUL%2C%20Afghanistan%20%E2%80%94%20Afghanistan's%20Taliban%20rulers,on%20women's%20rights%20and%20freedoms

J. Armitage Robison, The Passion of S. Perpetua: Contributions to Biblical and Patristic Literature, p. 44.

https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2023/01/world-failing-130-million-girls-denied-education-un-experts

https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_ngozi_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story

A Will to Change, bell hooks

Every single person, including men, is harmed within a patriarchy.

https://imaginenoborders.org/pdf/zines/UnderstandingPatriarchy.pdf

In her illuminating essay Medieval Women Book Owners: Arbiters of Lay Piety and Ambassadors of Culture, Susan Groag Bell reviews the financial resources necessary to purchase a medieval manuscript such as we saw coming out of 14th/15th century Europe. It would require the average non-privileged person an entire year’s salary to afford one book in Yolande of Aragon’s extensive library. The written word was long gate-kept by privilege and patriarchy.

Jones, D. (2021). Powers and thrones: a new history of the Middle Ages

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2707524?read-now=1&seq=7

Vibia Perpetua's Diary: A Women's Writing In A Roman Text Of Its Own, Melissa Perez, 2009

JESUS AS HERO IN THE VERGILIAN "CENTO" OF FALTONIA BETITIA PROBA, Elizabeth A. Clark and Diane F. Hatch

https://archive.org/details/pilgrimageofethe00mccliala/mode/1up?view=theater_

Studying Medieval Women edited by Nancy F. Partner, brooklynmuseum.org/eascfa/dinner_party/

Regendering Radegund? Fortunatus, Baudonivia and the Problem of Female Sanctity in Merovingian Gaul, Published online by Cambridge University Press

Conti, Aidan. “The Literate Memory of Hugeburc of Heidenheim.” Feminist Approaches to Early Medieval English Studies, edited by Robin Norris et al., Amsterdam University Press, 2023, pp. 317–42. JSTOR, doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv32dnb90.15

Atkinson, Clarissa W. “Spiritual Motherhood: Extraordinary Women in the Early Middle Ages” The Oldest Vocation

Wilson, Katharina M. Hrotsvit and the Artes: Learning Ad Usum Meliorem

The Worlds of Medieval Women: Creativity, Influence, and Imagination and Sara Ahmed, Living a Feminist Life (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), 1.

LILIE, RALPH-JOHANNES. “Reality and Invention: Reflections on Byzantine Historiography.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers, vol. 68, 2014, pp. 157–210. JSTOR, jstor.org/stable/24643758

Gillis, F. M. (1924). Matilda, Countess of Tuscany. The Catholic Historical Review, 10(2), 234–245. jstor.org/stable/25012072

Bugyis, K. (2015). Envisioning Episcopal Exemption: The Life of Christina of Markyate. Church History, 84(1), 32–63. jstor.org/stable/24537290 and fsuspecialcollections.wordpress.com/201…

FINDLEY, BROOKE HEIDENREICH. “Does the Habit Make the Nun? A Case Study of Heloise’s Influence on Abelard’s Ethical Philosophy.” Vivarium 44, no. 2/3 (2006): 248–75. jstor.org/stable/41963758

https://guides.loc.gov/feminism-french-women-history/famous/heloise

Femina, A New History of the Middle Ages, Through the Women Written Out of It by Janina Ramirez

Medieval Women’s Writing, by Diane Watt

Borroff, Edith. “Women Composers: Reminiscence and History.” College Music Symposium 15 (1975): 26–33. jstor.org/stable/40375087

Wonderful read! It makes me think about all the women we don’t know about that were erased from history. It’s got my creative mind thinking.

Great post! As a former double major in history and women's studies, all your work is music to my angry, tired ears. Keep it up!