This is the second part of a three part series, be sure to check out part one: here.1

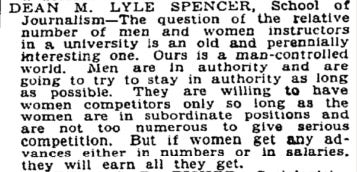

December 15, 1935, was a chilly day in New York City. The sleepless city would soon be hit with a New Year sleet storm, though this particular Sunday in the middle of December would stubbornly hold on to temperatures in the high teens. Seemingly the perfect Sunday to sit fireside and bask in heat and light alike, perhaps perusing The New York Times, feeling more a citizen of the world within it’s pages than without. An easy to miss write up occupying a tiny column in the Colleges and Universities section reported that an English professor at Syracuse catalyzed a university-wide debate after his criticism of the rise in female educators.2 The Times—wearing its newish mask of progressive communique—was sure to capture Doris Newton of the sociology department’s warning that such thoughts were a “dangerous admission on the part of man teachers”3 in order to support the journalist’s advocate-esque title. Yet, the patriarchal news outlet elegantly concluded the discourse on female inferiority with the words of Dr. Spencer Parratt, a political scientist, confidentially asserting that he just hadn’t yet met any of those lady instructors that “attained a real grasp of subjects along this line.”4

If the misogyny was too much to stomach in the section of higher learning, flipping to the Book Reviews would do little to alleviate the ick. After countless exposés of Great Men and the writers of Great Men, a proud and visually engaging review of a historical biography recently published by Samuel Putnam dared to change the tone...maybe. Putnam, in his research of the romance languages, had stumbled upon the author of the Heptaméron: one Marguerite of Navarre, a princess of France who would later in life become queen of Navarre through her second marriage. (Highlighted below as the second to last woman writer of the original Notes series.)

Marguerite was an incredible woman: well educated, influential, compassionate, determined, charitable in the financial sort of way while also equally as charitable with her time and energy, and was entirely devoted to seeing a more equitable future. This princess of France, like Isabelle of Portugal before her, and Christine de Pizan before her, and Hildegard of Bingen before her, and Eleanor of Aquitaine before her, and Empress Matilda before her—you get the point, right?—experienced immense influence throughout Europe. Leaders and humanist scholars alike were drawn to Marguerite's paradigm, praising her work for its intellectual depth alongside its emotional richness. Because of Marguerite’s endless accomplishments and forward-thinking, Putnam was confident in his assessment that she was the ‘first modern woman.” A lovely honorific, if not a little misplaced.

Did Putnam declare Marguerite the first modern woman because she had an education that “gave her a mental equipment of a quality enjoyed by no other woman of the century…”?5 Or perhaps it was because she sought intellectual pursuits such as writing, philosophy, and debate? Or maybe it was because she changed the landscape of French literature with her literary form influenced by other cultures? Perhaps her advocation of education for all? It was none of that. In fact, it was Marguerite’s work in the realm of social service which earned her this honorific from a man 400 years her junior. Marguerite’s exceptional intellect was all well and dandy, but what really mattered, at least in the eyes of Samuel Putnam, was her service to others, a credit to her gender.

It is too easy to dismiss Putnam’s assessment of the phenomenal, incomparable Marguerite as a ‘product of his time,’ but as we’ve reviewed in Part One of this series—and frankly every other post in my archive—women have always pushed back against the patriarchal narrative that any woman that exhibits an ounce of intellect is somehow unique and different than others among her gender, a gender which somehow has earned her the responsibility of care-for-all.

As women continue to dominate college campuses, we will continue to see men such as “Taylor Swift’s boyfriend’s teammate”6 patriarchally-postulate, insisting upon the return of medieval gender roles. As women continue to out earn men in the realm of higher education, we will continue to see the demonization of not just the woman, but the educated woman, the woman insistent on not just writing down her words, but daring enough to share them in a patriarchy-informed world.

I am honored to share the women of Notes 16-317 with you. May we continue to uplift women’s words in a world hellbent on erasing them.

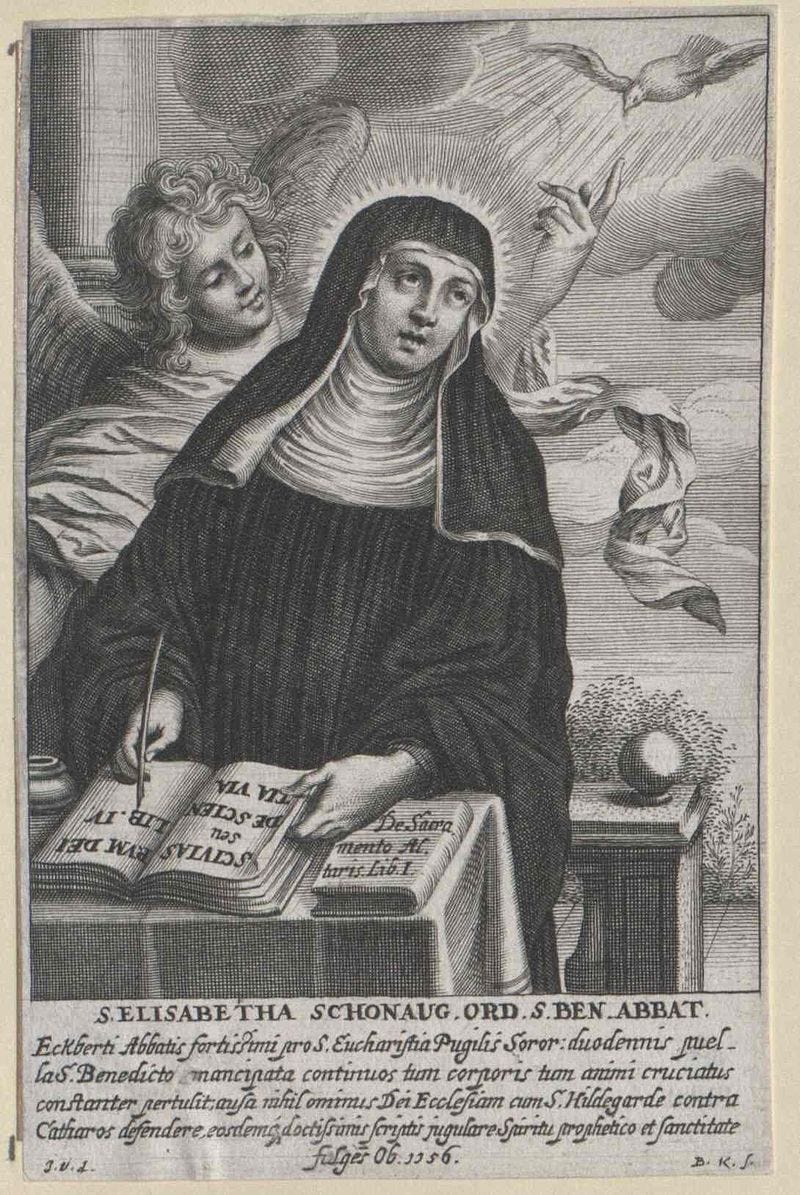

16. Elisabeth of Schönau - 1129-1164

Like Hildegard before her, Elisabeth transcribed her “innovative ideas and gender conceptions”, directly challenging the view of the feminine within the patriarchal church structure of the Middle Ages. Elisabeth of Schönau, also known as Saint Elisabeth, was a German Benedictine visionary and writer who lived during the 12th century. Born in Cologne, Germany, in 1129, Elisabeth entered the Benedictine monastery of Schönau at a young age. She is known for her mystical experiences, including visions and revelations, which she recorded in her writings. In 1156 Elisabeth visited Hildegard and, encouraged by her work, began writing Liber Viarum Dei, "The Book of God's Ways," whose subject was the various paths that lead to spiritual fulfillment.”

“Like Hildegard, Elisabeth suffered intense doubts about her calling. Her earliest revelations were associated with severe physical and emotional anguish, which eventually subsided.” Self-doubt, a common thread between our modern day experience within a patriarchy and that of our foremothers within the same patriarchal social structures, women such as Elisabeth sought to challenge the narrative, even within confined realities. “Drawing up on the tradition of Old Testament female prophets such as Judith, Hilda, Deborah, and Jael to serve as models for her own inspired work, Elisabeth resolved the problem of female authority. She wrote:

“In order to enthuse the souls of women, a woman judged, a woman decided, a woman prophesied, a woman triumphed and, in the midst of the fighting troops, taught men the art of war under feminine command.”8

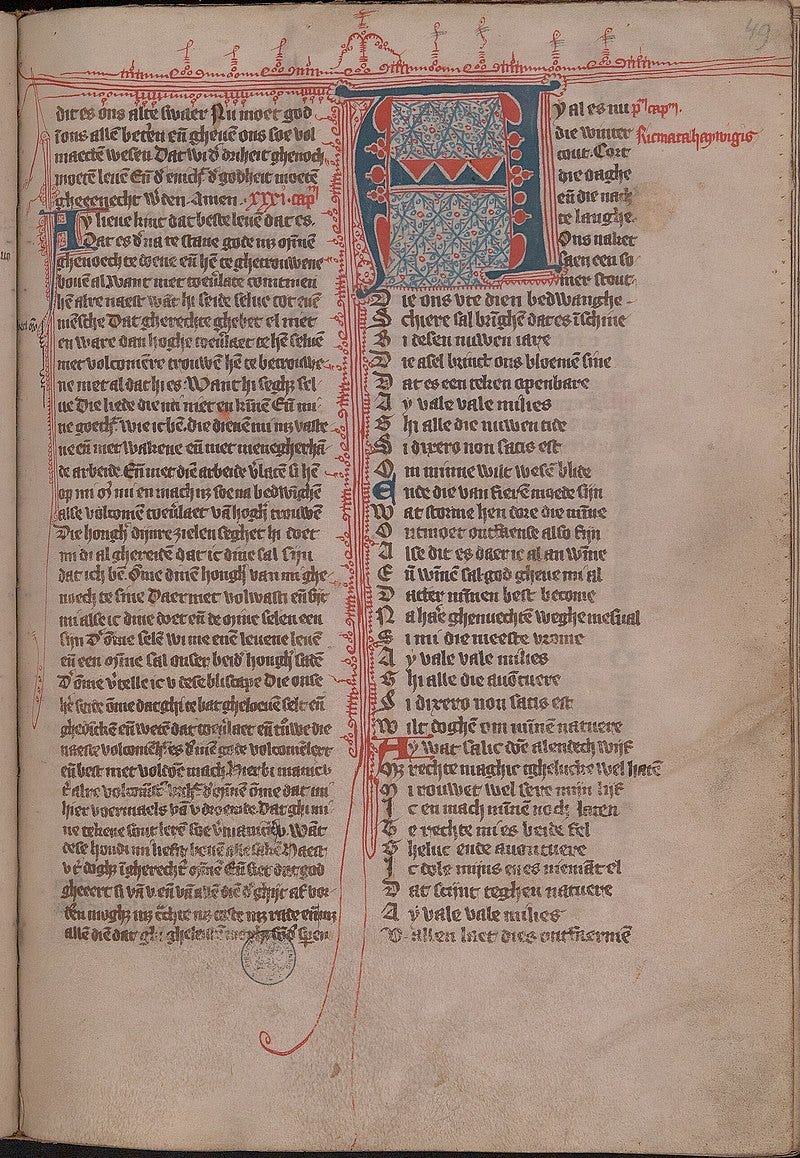

17. Hadewijch of Brabant - 1200-1260

Hadewijch of Brabant, also known as Hadewijch of Antwerp, was a 13th-century mystic and poet from the Low Countries, now Belgium. Not much is known about her life, but her writings have left a profound impact on the history of Christian mysticism. She is believed to have been a beguine, a woman who lived a religious life outside of a convent and perhaps even a leader among the beguines. Hadewijch's works, written in Middle Dutch, are characterized by their passionate and intense expression of divine love.

Hadewijch's writing explores themes of spiritual growth, the soul's relationship with God, and the nature of divine love. Her poetry is known for its intricate symbolism and profound theological insights. She wrote about the journey of the soul towards union with god, emphasizing the importance of contemplation.

All Things, by Hadewijch (translated into English by Jane Hirshfield):

All things

are too small

to hold me,

I am so vast

In the Infinite

I reach

for the Uncreated

I have

touched it,

it undoes me

wider than wide

Everything else

is too narrow

You know this well,

you who are also there9

18. Beatrice of Nazareth - 1200-1268

Beatrice of Nazareth was born in the city of Tienen in present-day Belgium around 1200 and entered the Cistercian convent of Bloemendaal near Antwerp at a young age. Establishing her own convent as prioress in 1237, Beatrice was an influential woman, creative, deeply spiritual, and well-educated.10

Most of Beatrice’s writing has been lost to us, leaving only a single surviving credited work, Uan seven manieren van heileger minnen [Seven Ways of Holy Love], attributed to her in 1926, a full seven and a half centuries after her death.

Beatrice, like too many other women, has had her patriarchal protest largely ignored. For she wrote in the vernacular [Middle Dutch] instead of the patriarchal-revered Latin, making her work more accessible to lay individuals outside of the ecclesiastically educated. (Much like women’s later use of individual Book of Hours, an hourly prayer book often written in the vernacular language, utilized as not just a spiritual tool, but an instructive one for girls, and women, with limited access points to education. Private personalized spirituality versus public patriarchal religion.)

Tiny acts of feminism, largely ignored or purposefully excluded by patriarchal histories.

—

On Seven Ways of Holy Love, by Beatrice of Nazareth, translated by Wim van den Dungen from Medieval & Modern Dutch to English (a snippet from the full length work which can be read online)

Seven ways of love come out of the highest and work back to the highest.

The first is a desire actively flowing out of love. Long has it to rule (in) the heart before dispelling every resistance thoroughly, and it cannot but work with strength and intelligence, courageously growing in all of this.

This first way is a desire most certainly stemming from love, for the good soul wanting to follow faithfully and to love enduringly, is being drawn on by the craving of this desire –most strongly to be loved and guarded– to exist in the purity, freedom and nobility in which she is made by her Creator, after His image and to His resemblance.11

“She.”

19. Mechthild of Magdeburg - circa 1207-1280s

Women have long criticized the double standard of the patriarchy, acknowledging the mental acrobatics needed to balance being both virtuous and powerful in a world that paradoxically suggests these two traits can coexist. Today’s writer, Mechthild von Magdeburg, was one such woman. Born into a noble Saxon family circa 1207, Mechthild was the first mystic to write in Low German, once again favoring vernacular over patriarchal Latin like Beatrice before her.

Despite living in a male-dominated society, Mechthild fearlessly challenged traditional gender roles and power structures through her writings and visions. Her works, such as "The Flowing Light of the Godhead," not only expressed her deep spiritual experiences but also questioned societal norms and expectations placed on women.

“Particularly important is the fact that Mechthild was an "aware" woman and, for a semi cloistered nun, perhaps too aware for her targets and detractors, who might have wished that the cloister would afford them more protection. Because of this awareness, she becomes for us a woman of two worlds: one, the intensely spiritual, visionary realm in which actuality is suspended and the soul takes over, moving in the highly idealised world of the chivalric society which was slowly dying out at the end of the thirteenth century; the other, the secular world of politics, decadence and wrong-doing, much of which affected the Church and thus detracted from its professed mission of saintliness.”12

Being aware, being awake, being woke isn’t new. This is yet another patriarchal phallusy.

20. Clare of Assisi - circa 1194-1253

Clare of Assisi, a prominent figure in the Catholic Church, is often celebrated for her radical devotion to poverty, prayer, and service. Clare defied societal norms of her time by rejecting a life of luxury and privilege to embrace a life of simplicity and humility. Born into a noble family, she chose to follow the teachings of St. Francis of Assisi and founded the Order of Poor Ladies, now known as the Order of Saint Clare. Clare's commitment to living in poverty and helping the poor challenged the traditional roles of women in medieval society. We know Clare largely through the hagiography written of her, but also through her letters, some of which are still preserved today.

Clare believed in the equality of all individuals and dedicated her life to serving those in need, regardless of their social status. Clare's unwavering faith and determination continue to inspire women around the world to break free from societal constraints and pursue their own paths with strength and conviction. In a world where women's voices were often silenced, Clare of Assisi remains a powerful symbol of female empowerment and resilience.13

21. Agnes of Bohemia - 1211 - 1282

Ally and friend to Clare of Assisi, Agnes of Bohemia was also a woman born into privilege whom chose poverty and service over the life prescribed to her. Agnes of Bohemia, later becoming Saint Agnes Prague, was “the youngest daughter of King Otakar Přemysl and his wife, Queen Constance. “Agnes rejected an offer of marriage from Emperor Frederick II and chose instead the life of a Poor Sister of Saint Damian. The sisters of San Damiano lived without regular income from property, and refused all papal and secular privileges other than the privilege of living without possessions. Having known both the comforts of courtly life as well as the austerity of monastic life, Agnes, who was more personally suited to austerity than to luxury, chose to embrace the lifestyle of San Damiano.”

Strong, community-focused women were a massive source of inspiration to Agnes, seeing the works of women propelling culture forward whilst equally focusing on community support drove her to dedicate her own life to living without possessions while serving others. Agnes was instrumental in establishing hospitals and charitable institutions in Bohemia, leaving a lasting impact on the community. While she did not write any known literary works, she is known for her extensive correspondence with important religious figures of her time, including Pope Gregory IX and Saint Clare of Assisi. Agnes of Prague's letters reveal her deep spirituality, and dedication to serving the poor while offering valuable insights into the religious and social context of 13th century Europe.14

22. Marguerite d'Oingt - circa 1240-1310

“Marguerite d'Oingt (1240-1310), a Carthusian prioress from Poleteins, does not fit neatly with the affective mystics of the later Middle Ages, whose emphasis upon individual experiences of the divine characterizes what almost qualifies as a distinct genre within the category of revelation literature Her writings—the Pagina Meditationum, the Speculum, a Vita of Saint Beatrice d'Ornacieux, and a handful of letters—do not express a particularly personal or personalized relationship with God, what John Hirsh describes as a "felt relationship between a divine being and a human agent." Instead, she represents herself as a person who has achieved, through reflection and with the help of divine grace, what anyone could presumably achieve through a similar reflexive process.”15

Marguerite challenged the traditional roles imposed on women by engaging in intellectual pursuits and expressing her thoughts through her writing. Her works, including her religious texts and poetry, reflect her intelligence, creativity, and determination to have her voice heard while also advocating for the importance of education, for all, once again signifying feminist believes far before the word existed. “Marguerite's work is grounded in the conviction that a proper understanding of words leads to a profound, intuitive understanding of the concepts that they signify.”

Marguerite d'Oingt's life serves as a testament to the resilience and strength of women throughout history who have fought against patriarchal constraints to make their mark on the world that was designed to erase them.

23. Marguerite Porete - 13th Century

Marguerite Porete was a French mystic and author who lived in the 13th century. She is best known for her work "The Mirror of Simple Souls," which was a significant piece of Christian mysticism. Marguerite believed in the concept of annihilation of the self in order to achieve union with God, a belief that was considered heretical by the authorities of the time. Despite warnings and excommunication from the Church, she continued to spread her ideas, leading to her arrest and eventual execution by burning at the stake in Paris in 1310.16

Marguerite’s writings and teachings have since gained recognition for their profound spiritual insights and their challenge to traditional religious authority. Her courage in standing by her beliefs in the face of persecution has inspired many throughout history. Women such as Marguerite were often punished for defying the patriarchal world order, if religion was self-practiced, then there would be no need for patriarchal religions to dictate the way in which your life was lived.

Today, Marguerite is remembered as a symbol of resistance against oppressive religious institutions and a champion of individual spiritual exploration. Her legacy continues to influence discussions on mysticism, spirituality, and the rights of individuals to express their beliefs freely.

24. Angela of Foligno - 1248-1309

Angela da Foligno, a medieval mystic and writer from Italy, was born around 1248. Renowned for her spiritual writings that reflected her deep mystical experiences and profound relationship with her God, Angela da Foligno holds a significant place in the history of Christian mysticism. Her writings offer readers a glimpse into the inner workings of a soul devoted to seeking union with the divine.17

Angela's work is noted for its emotional intensity, honesty, and profound insights into the nature of spirituality and the enmeshment of the human soul.

At 40, Angela experienced a spiritual transformation that led her to dedicate her life to God. Despite facing criticism and skepticism from her male counterparts, Angela fearlessly pursued her spiritual calling and became a beacon of inspiration for women seeking autonomy and liberation in a patriarchal society.

25. Catherine of Siena - 1347-1380

Catherine of Siena, born in 1347 in Siena, Italy, was the 23rd child of Jacopo and Lapa Benincasa. Catherine's importance as a writer cannot be overstated. The Dialogue of Divine Providence, a theological and spiritual treatise, is structured as a conversation between the soul, representing Catherine herself, and God. This innovative narrative technique allowed Catherine to explore deep theological concepts in an accessible manner, bridging the gap between the divine and the mundane, connecting with human emotion. Her writings, characterized by their vivid imagery and persuasive eloquence, were instrumental in addressing the spiritual and social tumult of her time. Through her letters, she engaged with popes, royalty, and political leaders, advocating for peace and the reform of the Church. Catherine’s influence upon European medieval religious culture was significant, so much so that she “convinced Pope Gregory XI to return the papacy from Avignon to Rome.”18

Catherine of Siena's legacy as a writer transcends her era, contributing significantly to Christian mysticism and theology. Catherine's life and works embody the power of spiritual conviction, whatever that may look like for you, and the potential of the written word to effect change.

26. Birgitta of Sweden - circa 1303-1373

Birgitta of Sweden, born in 1303 and passing in 1373, was a mystic and saint whose contributions to literature and religion remain influential centuries after her death. Born into the Swedish nobility, Birgitta's life took a spiritual turn after the death of her husband, Ulf Gudmarsson. With this loss, she began to experience visions which she believed were messages from her God.

Birgitta meticulously documented her visions. These were compiled into several works, the most well-known being the Revelationes. This collection of her visions and spiritual experiences offers deep insights into her theology and spirituality, reflecting her concerns with the moral and spiritual reform of the Christian Church and society. Her writings not only provide a window into the religious life of the 14th century but also present her as a pioneering female voice in a time when women's contributions to literature and theology were often overlooked or undervalued.

“Birgitta of Sweden, is one of the most extraordinary women of the Middle Ages who over a period of nearly thirty years served as mouthpiece of God, denouncing moral corruption and chastising both secular and ecclesiastical leaders for their depravity.” 19

Women have long been advocating against patriarchal realities rife with contradictions and double-standards.

27. Julian of Norwich - 14th Century

Type ‘god is a woman’ into google and an array of Ariana Grande videos and sites pop up as a result, but 600 years before Ariana’s feminine deity emitted from the radio-waves, Julian of Norwich daringly wrote of god’s femininity and mother-like qualities. In 1373, at age 30 1/2, Julian lay on her sickbed accepting of what seemed her imminent demise, surrounded by loved ones to be with her as she endeavored on her next journey into the afterlife.

During this time, she received fifteen showings, or what we may think of as visions, depicting the Passion, Creation, the Virgin Mary, and more. The next night, she experienced another showing, making 16 in total. Julian, fortunate to make a full recovery, was forever altered by the experiences she witnessed within her own mind. These visions led Julian to seek solitude in a religious setting, becoming an anchoress of Norwich where she would remain a recluse for the rest of her days, dying sometime after 1415 and prior to 1420.20

Julian’s reclusive nature meant that her works were void of commentary on social and political events of her time, however, because of the solitary nature of her life she was free from being labeled as a heretic, allowing her to write in any way she felt fit, including gender bending the deity beloved by the patriarchal church structure and comparing god’s nature to that of a Mothers. Julian’s writing, now known as the Revelations of Divine Love, are the oldest surviving works of a woman written in English (that is known to us now). And like the women writers before her, Julian’s work was innovative and personally motivated, allowing her to move from object in a patriarchal world to subject of her own creation, becoming genderless in her own spirituality.

Though little is known of Julian’s early life, it is often assumed that Julian knew motherhood firsthand, made evident through her descriptions of god’s mothering nature, and perhaps lost her family to the plague which was ripe in England during her lifetime. Julian’s work remained hidden until the sixteenth century, making its way to France, ultimately ending in Cambrai where nuns preserved it until the French Revolution, when they feared execution, fleeing to England bringing Julian home with them.21

28. Margery Kempe - 1373-1438

In 1943 Hope Emily Allen was deep in research in the library of Colonel Butler-Bowdon of Pleasington Old Hall, Lancashire, where she identified a medieval autobiography written by a woman. Not only was this a medieval autobiography, it was the first autobiography to be written in English by any person, regardless of gender. The identified manuscript was the Book of Margery Kempe.

Margery was an upper-class woman who had lived 500 years prior in Norfolk, and much like Julian of Norwich before her, she sought out a religious existence later in life, feeling at odds with her patriarchal prescribed purposes. “In her autobiography Margery Kempe unfolds for us the anxieties and experiences of a religious woman whose life was dedicated to the service of God. No English writer, hitherto, had committed to writing so intimate, revealing and human an account of his life and thoughts.”22 (Quote pulled from a text printed in 1976, but you have to love the glaring patriarchal bias.)

The Book itself is an anomaly. Margery was neither part of the English nobility, nor was it a hagiographical text which was more typical of the time. She was a middle-class wife and mother, a subclass we rarely get contemporary insight into due to patriarchal histories. “Written in simple and rather crude Middle English, it would not have been preserved for it’s literary quality. Yet the very simplicity of the writing style is what makes it so interesting. It has not been overworked by scribes fluent in rhetorical and literary devices; it retains a direct quality that speaks to us across time.”23

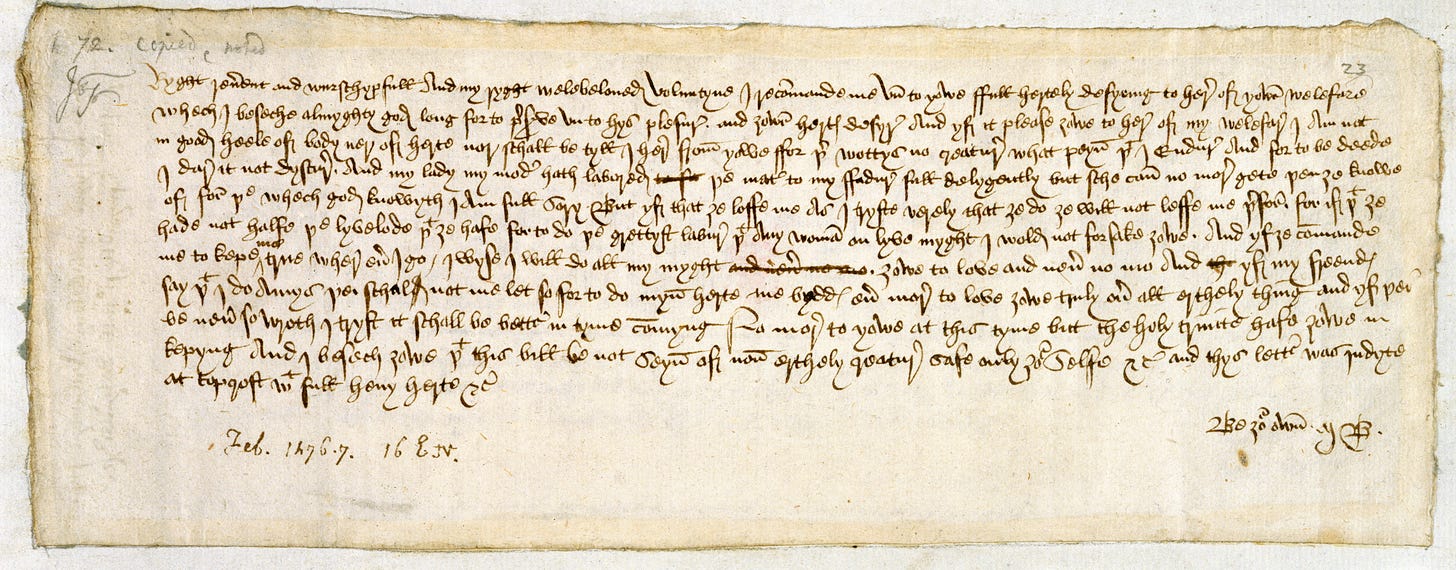

29. The Paston Women - 15th Century

The Paston family offers a significant glimpse into daily life during the Middle Ages, with a collection of over a thousand documents spanning from 1422 to 1509, covering three generations of Paston commentary and legal records. Living through the turbulent era of the War of the Roses, the Paston family, a Norfolk gentry family, navigated challenging times in English history.

Margaret Paston, the matriarch of the Paston family during this period, highlighted the crucial role of women, literacy, and education in medieval England through her correspondence. Managing family estates, business affairs, and defending lands during conflicts and outbreaks, Margaret demonstrated her competence and willingness to protect her family's interests while also allowing us a glimpse into the oppressive hierarchical structure of the patriarchal nuclear family of the Middle Ages (and what Christian nationalists are working towards today).24

Out of the 421 documents from the immediate family, 107 were authored by Margaret, many of which were exchanges with other women in the Paston clan. Diane Watt notes, "The letters of the Paston women showcase female self-expression and highlight the significant role women played in both household and wider Norfolk society."25

These letters provide valuable insights into daily life in the late Middle Ages and the linguistic transition from Old English to Early Modern English.

30. Queen Margaret of Navarre - 1492-1549

Margaret was a prolific writer, best known for her work Heptameron, a collection of novellas that echo the style of Boccaccio's Decameron. Through her writings, Margaret explored themes of love, fidelity, and the social conditions of women, offering a nuanced portrayal of female agency and intellect at a time when women's voices were often marginalized. Her literary output was not merely for entertainment; it was a bold assertion of her intellect and a challenge to the gender norms of her era. As a reader, her voracious appetite for knowledge and her engagement with the works of contemporary humanists and reformers underscored her role as an intellectual in her own right, navigating and contributing to the major religious and philosophical debates of her time.

Beyond her personal achievements in literature, Margaret's legacy is also defined by her role as a patron of the arts. Her court became a refuge for scholars, writers, and artists, many of whom were at the forefront of the Renaissance and the Reformation movements. Through her patronage, she fostered an environment of intellectual freedom and artistic expression, enabling the flourishing of ideas and works that might have otherwise been suppressed. Her support of figures like François Rabelais and Clément Marot helped to shape the cultural and intellectual landscape of France and beyond, making her court a beacon of enlightenment and progress.

As a writer, reader, and patron, Margaret embodied the spirit of the Renaissance, championing the causes of education, artistic expression, and intellectual freedom. Her legacy is not just one of literary or artistic achievement but of feminist resistance and empowerment, marking her as a pivotal figure in the history of women's contributions to culture and society.

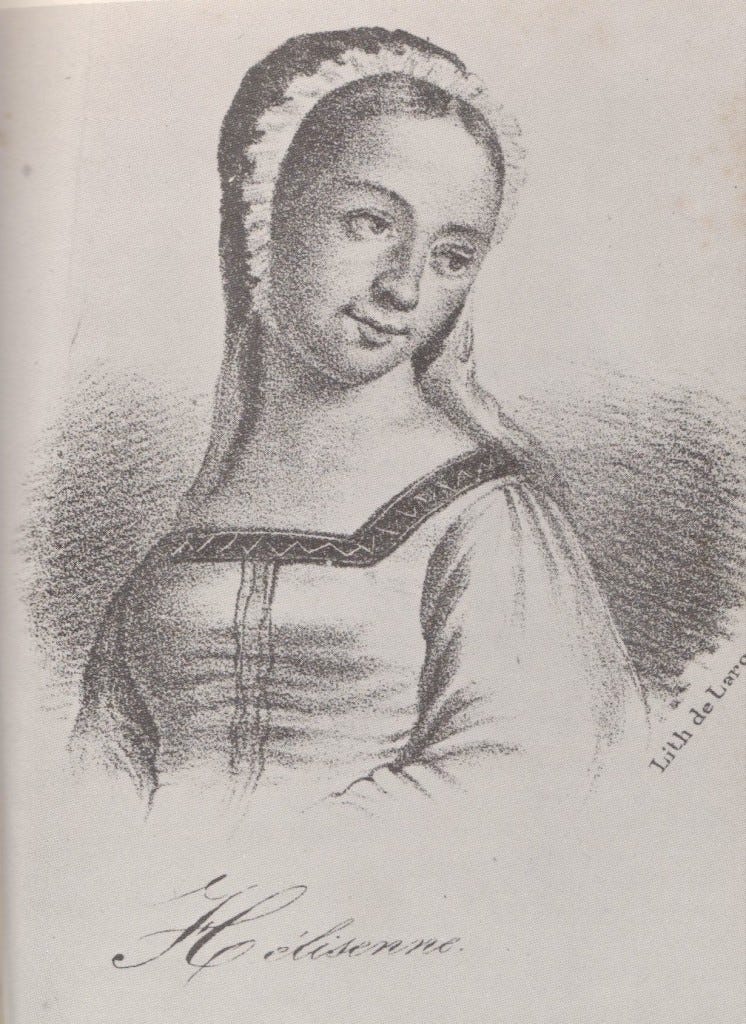

31. Helisenne de Crenne - circa 1510-1552

Hélisenne de Crenne, a pseudonym for Marguerite Briet, is a figure whose contributions to literature and feminist thought in the 16th century remain profoundly influential, albeit not as widely recognized as they deserve to be. In an era dominated by male voices, de Crenne carved out a space for female expression and introspection that was pioneering for her time. Her work not only reflects the tumultuous personal experiences of her life but also serves as a testament to the resilience and creativity of women navigating the constraints of their societal roles. Her legacy is not merely in the beauty of her prose or the depth of her narratives but in her courage to speak out against societal constraints and envision a world where women could freely express themselves.

Born around 1510 in Abbeville, France, de Crenne was an intellectual and writer who dared to explore themes of love, despair, and female agency in her literary works. Her most notable contributions include Les Angoysses douloureuses qui procèdent d'amours, a semi-autobiographical novel that intertwines her own experiences with those of her fictional characters, and Les Epistres familieres et invectives, a collection of letters that offer insight into her thoughts and feelings on a range of subjects. Through these writings, de Crenne not only challenged the patriarchal norms of her time but also laid the groundwork for future generations of women writers.

As we continue to fight for gender equality and women's rights, the life and works of Hélisenne de Crenne remind us of the power of literature to challenge, inspire, and transform societies.

I can’t be bothered to fix the voice over. Women 16-31*, whoopsies!

https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1935/12/15/87890300.html?pageNumber=107

Ibid.

Ibid.

https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1935/12/15/87890761.html?pageNumber=54

I’m doing my best here, ok? 🤣 16*

Storey, Ann. “A Theophany of the Feminine: Hildegard of Bingen, Elisabeth of Schönau, and Herrad of Landsberg.” Woman’s Art Journal 19, no. 1 (1998): 16–20. doi.org/10.2307/1358649

https://www.poetry-chaikhana.com/Poets/H/Hadewijch/Allthings/index.html

“About which we want to speak now”: Beatrice of Nazareth’s Reason for Writing Uan seven manieren van heileger minnen by Kris Van Put via The Journal of Medieval Religious Cultures, Volume 42, Number 2, 2016, pp. 143-163

Medieval Women Book Owners: Arbiters of Lay Piety and Ambassadors of Culture By Susan Groag Bell

Koch, Regina M. “MECHTHILD VON MAGDEBURG, WOMAN OF TWO WORLDS.” 14th Century English Mystics Newsletter 7, no. 3 (1981): 111–31. jstor.org/stable/20716351

“FRANCIS AND CLARE OF ASSISI: DIFFERING PERSPECTIVES ON GENDER AND POWER.” Franciscan Studies 63 (2005): 11–25. jstor.org/stable/41975340

https://www.jstor.org/stable/41975272?read-now=1&seq

https://www.jstor.org/stable/20716542?read-now=1&seq

https://www.jstor.org/stable/40390063?read-now=1#page_scan_tab_contents

http://www.jstor.org/stable/40059491

https://www.jstor.org/stable/40059491?read-now=1#page_scan_tab_contents

http://www.jstor.org/stable/40920383

Ramirez, Janina. Femina : A New History of the Middle Ages, through the Women Written out of It. London: WH Allen, 2022.

https://research.aber.ac.uk/en/publications/medieval-womens-writing

Ramirez, Janina. Femina : A New History of the Middle Ages, through the Women Written out of It. London: WH Allen, 2022.

Bennett, H.S. Six Medieval Men & Women. New York: Atheneum, 1976.

Ibid.

https://research.aber.ac.uk/en/publications/medieval-womens-writing

“This is yet another patriarchal phallusy” gave me a good laugh. Great piece as always!

It is still common for women to be the ones advising men on intellectual matters, politics, and making important business decisions (mothers, wives, sisters). They never get recognition and only a rare few are highlighted as famous figures making contributions to society🙏